The brilliant composer Alan Hovhaness's haunting second symphony is called Mysterious Mountain -- named, he said, because "mountains are symbols, like pyramids, of man's attempt to know God." Having spent a lot of time in my twenties and thirties hiking in Washington State's Olympic and Cascade Ranges, I can attest to the fact that there's something otherworldly about the high peaks. Subject to rapid and extreme weather changes, deep snowfall in the winter, and -- in some places -- having terrain so steep that no human has ever set foot there, it's no real wonder our ancestors revered mountains as the abode of the gods.

Hovhaness's symphony -- which I'm listening to as I write this -- captures that beautifully. And consider how many stories of the fantastical are set in the mountains. From Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth to Tolkien's Misty Mountains and Mines of Moria, the wild highlands (and what's beneath them) have a permanent place in our imagination.

Certain mountains have accrued, usually by virtue of their size, scale, or placement, more than the usual amount of awe. Everest (of course), Denali, Mount Olympus, Vesuvius, Etna, Fujiyama, Mount Rainier, Kilimanjaro, Mount Shasta. The last-mentioned has so many legends attached to it that the subject has its own Wikipedia page. But none of the tales centering on Shasta has raised as many eyebrows amongst the modern aficionados of the paranormal as the strange story of J. C. Brown.

Brown was a British prospector, who in the early part of the twentieth century had been hired by the Lord Cowdray Mining Company of England to look for gold and other precious metals in northern California, which at the time was thousands of square miles of trackless and forested wilderness. In 1904, Brown said, he was hiking on Mount Shasta, and discovered a cave. Caves in the Cascades -- many of them lava tubes -- are not uncommon; two of my novels, Signal to Noise and Kill Switch (the latter is out of print, but hopefully will be back soon), feature unsuspecting people making discoveries in caves in the Cascades, near the Three Sisters and Mount Stuart, respectively.

Brown's cave, though, was different -- or so he said. It was eleven miles long, and led into three chambers containing a king's ransom of gold, as well as 27 skeletons that looked human but were as much as three and a half meters tall.

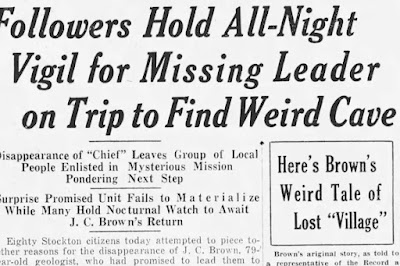

Brown tried to drum up some interest in his story, but most people scoffed. He apparently frequented bars in Sacramento and "told anyone who would listen." But then a different crowd got involved, and suddenly he found his tale falling on receptive ears.

Regular readers of Skeptophilia might recall a post I did last year about Lemuria, which is kind of the Indian Ocean's answer to Atlantis. Well, the occultists just loved Lemuria, especially the Skeptophilia frequent flyer Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy. So in the 1920s, there was a sudden interest in vanished continents, as well as speculation about where all the inhabitants had gone when their homes sank beneath the waves. ("They all drowned" was apparently not an acceptable answer.)

And one group said the Lemurians, who were quasi-angelic beings of huge stature and great intelligence, had vanished into underground lairs beneath the mountains.

In 1931, noted wingnut and prominent Rosicrucian -- but I repeat myself -- Harvey Spencer Lewis, using the pseudonym Wishar S[penley] Cerve (get it? It's an anagram, sneaky sneaky), published a book called Lemuria, The Lost Continent of the Pacific (yes, I know Lemuria was supposed to be in the Indian Ocean; we haven't cared about facts so far, so why start now?) in which he claimed that the main home of the displaced Lemurians was a cave complex underneath Mount Shasta. J. C. Brown read about this and said, more or less, "See? I toldja so!"

No comments:

Post a Comment