There's an unfortunate but natural tendency for us to assume that because something is done a particular way in the culture we were raised in, that obviously, everyone else must do it the same way.

It's one of the (many) reasons I think travel is absolutely critical. Not only do you find out that people elsewhere get along just fine doing things differently, it also makes you realize that in the most fundamental ways -- desire for peace, safety, food and shelter, love, and acceptance -- we all have much more in common than you'd think. As Mark Twain put it, "Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one's lifetime."

One feature of culture that is so familiar that most of the time, we don't even think about it, is how we write. The Latin alphabet, with a one-sound-one-character correspondence, is only one way of turning spoken language into writing. Turns out, there are lots of options:

- Pictographic scripts -- where one symbol represents an idea, not a sound. One example is the Nsibidi script, used by the Igbo people of Nigeria.

- Logographic scripts -- where one symbol represents a morpheme (a meaningful component of a word; the word unconventionally, for example, has four morphemes -- un-, convention, -al, and -ly). Examples include Egyptian hieroglyphics, the Cuneiform script of Sumer, the characters used in Chinese languages, and the Japanese kanji.

- Syllabaries -- where one symbol represents a single syllable (whether or not the syllable by itself has any independent meaning). Examples include the Japanese hiragana script, Cherokee (more about that one later), and Linear B -- the mysterious Bronze-Age script from Crete that was a complete mystery until finally deciphered by Alice Kober and Michael Ventris in the mid-twentieth century.

- Abjads -- where one symbol represents one sound, but vowels are left out unless they are the first sound in the word. Examples include Arabic and Hebrew.

- Abugidas -- where each symbol represents a consonant, and the vowels are indicated by diacritical marks (so, a bit like a syllabary melded with an abjad). Examples include Thai, Tibetan, Bengali, Burmese, Malayalam, and lots of others.

- Alphabets -- one symbol = one sound for both vowels and consonants, such as our own Latin alphabet, as well as Cyrillic, Greek, Mongolian, and lots of others.

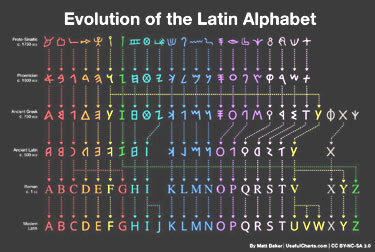

To make things more complicated, scripts (like every other feature of language) evolve over time, and sometimes can shift from one category to another. There's decent evidence that our own alphabet evolved from a pictographic script:

Note, for example, the evolution of our letter "A," from a cow's head (so presumably the symbol originally represented an actual cow or ox), becoming a stylized representation of a horned animal, and finally losing its pictographic character entirely and becoming a representation of a sound instead of an idea.

Not only do scripts evolve, they can be invented. (Obviously, they're

all invented, but most of the ones we know about are old enough that we don't know much about their origins.) Cyrillic, for example, was an creation of the Bulgarian

Tsar Simeon I, but he based it on three sources -- Greek, Latin, and

Glagolitic (a script used to write Old Church Slavonic), so it wasn't an invention

ex nihilo. The syllabic Cherokee script, however, was invented in the early nineteenth century by the brilliant Cherokee polymath

Sequoyah, to give his people a way to write down their own history (a script that became one of the first written languages of the Indigenous people of North America). In fact, it's a recently-invented script that brought this topic up today; a

paper last week in Current Anthropology looks at a writing system I'd never heard of, the Vai script of Liberia, invented by a collaboration of eight people in 1833 from motivation similar to Sequoyah's. Like Cherokee, it's syllabic in nature:

The paper looks at the interesting fact that even in the short time since its invention, Vai has evolved -- the symbols have simplified, and the script has "compressed" -- similar-sounding syllables eventually being represented by the same symbol.

"Visual complexity is helpful if you're creating a new writing system," said the study's lead author, Piers Kelly, of the Max Planck Institute, in

an interview with Science Alert. "You generate more clues and greater contrasts between signs, which helps illiterate learners. This complexity later gets in the way of efficient reading and reproduction, so it fades away." Also, as more and more people learn the writing system, it becomes regularized and standardized -- something that happens even faster when people switch from pen-and-paper to some kind of technological means of reproducing text.

It's why the recent tendency for People Of A Certain Age to bemoan the loss of cursive writing instruction in American public schools is honestly (1) kind of funny, and (2) swimming upstream against a powerful current. Writing systems have been evolving since the beginning, with complicated, difficult to learn, difficult to reproduce, or highly variable systems being altered or eliminated outright. It's a tough sell, though, amongst people who have been trained all their lives to use that script; witness the fact that Japanese still uses three systems, more or less at the same time -- the logographic kanji and the syllabic hiragana and katakana. It will be interesting to see how long that lasts, now that Japan has become a highly technological society. My guess is at some point, they'll phase out the cumbersome (although admittedly beautiful) kanji, which requires understanding over two thousand symbols to be considered literate. The Japanese have figured out how to represent kanji on computers, but the syllabic scripts are so much simpler that I suspect they'll eventually win.

In any case, it's fascinating to see how many different solutions humans have found for turning spoken language into written language, and how those scripts have changed over time (and continue to change). All features of the amazing diversity of humanity, and a further reminder that "we do it this way" isn't the be-all-end-all of culture.

***********************************

Like many people, I've always been interested in Roman history, and read such classics as Tacitus's Annals of Imperial Rome and Suetonius's The Twelve Caesars with a combination of fascination and horror. (And an awareness that both authors were hardly unbiased observers.) Fictionalized accounts such as Robert Graves's I, Claudius and Claudius the God further brought to life these figures from ancient history.

One thing that is striking about the accounts of the Roman Empire is how dangerous it was to be in power. Very few of the emperors of Rome died peaceful deaths; a good many of them were murdered, often by their own family members. Claudius, in fact, seems to have been poisoned by his fourth wife, Agrippina, mother of the infamous Nero.

It's always made me wonder what could possibly be so attractive about achieving power that comes with such an enormous risk. This is the subject of Mary Beard's book Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern, which considers the lives of autocrats past and present through the lens of the art they inspired -- whether flattering or deliberately unflattering.

It's a fascinating look at how the search for power has driven history, and the cost it exacted on both the powerful and their subjects. If you're a history buff, put this interesting and provocative book on your to-read list.

[Note: if you purchase this book using the image/link below, part of the proceeds goes to support Skeptophilia!]