The last two posts have been about biological extinction; today's, to continue in the same elegiac tone, is about language extinction.

A study in Ethnologue found that of the Earth's current seven-thousand-odd languages, 3,143 -- around forty-four percent -- are in danger of going extinct. Languages become endangered from a number of factors; when children are not taught as their first language, when there's government suppression, or when a different language has become the primary means of communication, governance, and commerce.

Of course, all three of those frequently happen at the same time. The indigenous languages of North and South America and Australia, for example, have proven particularly susceptible to these forces. In all three places, English, Spanish, and Portuguese have superseded hundreds of languages, and huge swaths of cultural knowledge have been lost in the process.

In almost all cases, there's no fanfare when a language dies. They dwindle, communication networks unravel, the average age of native speakers moves steadily upward. Languages become functionally extinct when only a few people are fluent, and at that point even those last holdouts are already communicating in a different language with all but their immediate families. When those final few speakers die, the language is gone -- often without ever having been studied adequately by linguists.

Sometimes, however, we can pinpoint fairly closely when a language died. Curiously, this is the case with Ancient Egyptian. This extinct language experienced a resurgence of interest in the early nineteenth century, due to two things -- the British and French occupations of Egypt, which resulted in bringing to Europe hundreds of priceless Egyptian artifacts (causing "Egyptomania" amongst the wealthy), and the stunning decipherment of hieroglyphics and Demotic by the brilliant French linguist Jean-François Champollion.

For a millennium and a half prior to that, though, Ancient Egyptian was a dead language. And as weird as it sounds, we know not only the exact date of its rebirth, but the date it took its last breath. Champollion shouted "Je tiens mon affaire!" ("I've figured it out!") to his brother on 14 September 1822.

And the last inscription was made by the last known literate native speaker of Ancient Egyptian on 24 August 394 C.E.

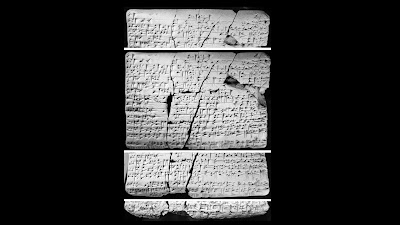

It's called the "Graffito of Esmet-Akhom," and was carved on the wall of a temple in Philae. It shows the falcon-god Mandulis, who was a fairly recent invention at the time, and like the Rosetta Stone, it has an inscription in hieroglyphics and Demotic:

The text reads:

Before Mandulis, son of Horus, by the hand of Esmet-Akhom, son of Nesmeter, the Second Priest of Isis, for all time and eternity. Words spoken by Mandulis, lord of the Abaton, great god.I, Esmet-Akhom, the Scribe of the House of Writings(?) of Isis, son of Nesmeterpanakhet the Second Priest of Isis, and his mother Eseweret, I performed work on this figure of Mandulis for all time, because he is fair of face towards me. Today, the Birthday of Osiris, his dedication feast, year 110.