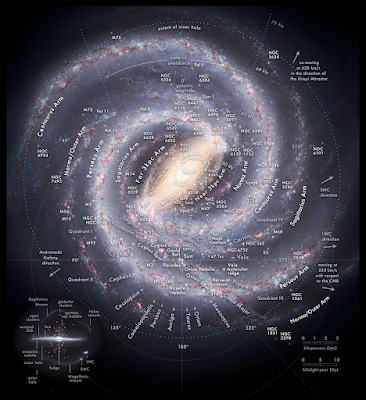

I've shown a bunch of people, and I've gotten answers from an electron micrograph of a sponge to a close-up of a block of ramen to the electric circuit diagram of the Borg Cube. But the truth is almost as astonishing:

It's a map of the fine structure of the entire known universe.

Most everyone knows that the stars are clustered into galaxies, and that there are huge spaces in between one star and the next, but far bigger ones between one galaxy and the next. Even the original Star Trek got that right, despite their playing fast and loose with physics every episode. (Notwithstanding Scotty's continual insistence that you canna change the laws thereof.) There was an episode called "By Any Other Name" in which some evil aliens hijack the Enterprise so it will bring them back to their home in the Andromeda Galaxy, a trip that will take three hundred years at Warp Factor 10. (And it's mentioned that even that is way faster than a Federation starship could ordinarily go.)

So the intergalactic spaces are so huge that they're a bit beyond our imagining. But if you really want to have your mind blown, consider that the filaments of the above diagram are not streamers of stars but streamers of galaxies. Billions of them. On the scale shown above, the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy are so close as to be right on top of each other.

What is kind of fascinating about this diagram -- which, by the way, is courtesy of NASA/JPL -- is not the filaments, but the spaces in between them. These "voids" are ridiculously huge. The best-studied is the Boötes Void, which is centered seven hundred million light years away from us. It is so big that if the Earth were at the center of it, we wouldn't have had telescopes powerful enough to see the next nearest stars until the 1960s, and the skies every night would be a uniform pitch black.

That, my friends, is a whole lot of nothing.

What I find most mind-bending about the whole thing, and in fact what sent me down this particular (extremely deep) rabbit hole this morning, is that the location of the filaments is thought to reflect quantum fluctuations in the matter immediately after the Big Bang, when the whole universe was only a fraction of a centimeter across. As inflation took over and the universe expanded, those tiny anisotropies -- unevenness in the composition of space -- were magnified until you have filaments which are densely filled and gaps where there is almost nothing at all, and the universe resembles a Swiss cheese made of stars.

Of course, I'm using "densely filled" in a comparative sense. The cold vacuum of space between the Sun and Proxima Centauri, the nearest star, really doesn't have much in it. Dust, comets, possibly a rogue planet or two. But even this is jam-packed by comparison to the Boötes Void and the others like it, wherein it is thought there are light-years of space without so much as a single hydrogen atom.

All of which makes me feel awfully small. Our determination to act as if what happens down here is of cosmic import is shaken substantially by looking up into the night sky. It's smashed to smithereens by considering the scale of the largest structures in the universe, which are threads of billions of stars making up a latticework -- and between which there is nothing but eternal silence and such profound darkness that it contains not even a single star close enough to see.

I don't know about you, but that makes me want to climb back under the covers and hug my teddy bear for a while.

****************************************

|