Before I start today's post, allow me to begin with a disclaimer: I am not claiming psychic abilities are impossible. I am not hostile to any attempts to demonstrate their existence scientifically. In fact, I would love it if all of the claims were true, because it would be wonderful fun to telekinetically control Tucker Carlson while he's on the air and make him unable to do anything but sing the theme song to SpongeBob SquarePants over and over, or put a deadly and horrific curse on Mitch McConnell so that he suddenly develops a soul or something.

But as my grandma was fond of saying, wishin' don't make it so. In science the usual progression of things is (1) produce unequivocal evidence that the phenomenon you've observed actually exists, (2) find correlations between that phenomenon and whatever you believe is causing it, and (3) show that those correlations actually do represent causation.

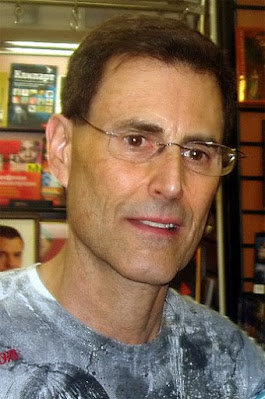

Polish "psychic"

Stanisława Tomczyk levitating a pair of scissors, which totally wasn't connected to her fingers by a piece of thread or anything (ca. 1909) [Image is in the Public Domain]

Unfortunately, a lot of psychic researchers get the whole thing backwards, which is a little maddening. Take the story I read yesterday in Mystery Wire about some research by the rather notorious Dean Radin, who has been for decades trying to put psychic stuff unequivocally on a scientific footing. While, like I said, I have no problem with this as a general goal, much about what Radin does sounds an awful lot like assuming your conclusion and then casting about for incidental evidence to support what you already believed was true.

Turns out Radin was the co-author of a paper in Elsevier called "Genetics of Psychic Ability: A Pilot Case-Control Exome Sequencing Study," that basically looked at genome sequencing people who self-reported a family history of psychic abilities and compared those sequences to people who self-reported no psychic abilities in their family heritage. And they found differences.

That, unfortunately, constitutes about the sum total of their findings, but Radin et al. proceeded to crow that they'd found a genetic basis for psychic ability. But amongst the (many) problems, here are a few that jump out right away:

- Out of a sample size of 1,000, only thirteen people reported a family history of psychic stuff. They then had to actively look for thirteen people who didn't, to use as a control. This seems like an awfully small sample size from which to draw such a profound conclusion.

- There was no indication that they ruled out other reasons for the similarities. Given that claims of psychic abilities have at least some tendency to be culture-dependent, isn't it at least possible that the common gene sequences they found were due to similar ethnic background?

- More reputable crowd-based human genomic studies -- such as the one being conducted by 23 & Me -- are still hesitant to assume the commonalities and differences they find in the DNA are causative of phenotype. Due to the phenomenon of pleiotropy (one gene, many effects) and complicating factors like epigenetics, the most I've seen them say is that (after hundreds of thousands of sequences analyzed) "you have a higher than average likelihood of having trait X." (Such as when I was told that I am likely to have hair that photo-bleaches in the sun -- which turns out to be true.)

- From their study, they concluded that being genetically psychic is the "wild type" and that we non-psychics are the mutants. Why, with a grand total of 26 people to compare, they decided this I can't tell, and that's even after reading the actual paper. Seems to me it's more along the lines of "the modern scientific approach has blunted our perception of the mystical oneness of reality that we once had in the past" stuff that you hear so often from these types.

- As I mentioned earlier, there has yet to be any sort of scientifically admissible evidence that psychic abilities exist, so looking for an underlying cause seems to be a tad premature.

Then, unfortunately, Radin launches off into the ionosphere during an interview with Mystery Wire's writer George Knapp. He describes another "experiment" (I hesitate even to dignify it by that name) in which a supposed double-blind experiment showed that people who drank tea that had been blessed felt happier than ones who had drunk unblessed tea. As if this weren't enough, Radin comes up with an inadvertently hilarious explanation:

So we used a little plant called Arabidopsis thaliana, which is in the mustard family. So it’s got [sic] a little weed. And a little weed is interesting because its genome was sequenced before the human genome. And it turns out that like most living creatures around the world have very similar DNA. [sic again] So if this plant has a disease that’s genetically based it has an analogue in humans. [Nota bene: This is where I started laughing.] So the plants are used for studying genetic diseases without using humans for it. [NB: No, they're not.] So, it also turns out that there are various mutations that are understood about this plant. And in particular, all living systems on earth have a protein called cryptochrome. So cryptochrome is interesting because it is a protein that is thought to have quantum properties. [NB: All molecules have quantum properties. That's kind of what "quantum property" means -- the behavior of matter and energy on extremely small scales.] So we thought, okay, let’s get an Arabidopsis plant, that is a particular mutation where it overexpresses cryptochrome, so when there’s blue light on it, the cryptochrome is activated, it overexpresses, it grows more. So we thought, well, maybe that would be an interesting target, to use for intention, because we think there may be a relationship between observing quantum systems, in this case of protein, and the response to that system. So again, under double blind conditions, the Buddhist monks have treated water, they have the same water that is not treated, the seeds are grown into two water mediums. And then there’s a variety of different measures you can take. One of which is called a hypocotyl. So the hypocotyl is the point where the stem begins from the seed up to the beginning of the leaves. So if it’s short and fat, it means that it’s a healthy plant, because it’s not using all of its energy to try to reach the surface or turn upside down or something. So short fat hypocotyl, we did nine repetitions of the experiment and got extremely significant differences, terms of magnitude is only a matter of a couple of millimeters. [sic] But so many experiments in such precise results, we can tell there was a really significant difference in growth, better growth with the treated water or the blessed water.

Yeesh. A hypocotyl a "couple of millimeters" longer constitutes "extremely significant results"? That rule out all other possible factors, including natural variability and the difficulty of measuring the stem of a small plant to millimeter accuracy?

And as an aside, beginning every other sentence with the word "So" is almost as annoying as the people who use "like" as, like, a punctuation in, like, every, like, thing they say. What it does not do is make you come across as an articulate intellectual.

Anyhow, I encourage you to read the Mystery Wire article, and (especially) the original paper, which is helpfully included therein. See if you think I'm being unwarrantedly harsh. And it's not that I expect scientists -- or anyone, really -- to be completely unbiased; they obviously can't start out from the standpoint that all possible explanations are on equal footing, and they understandably have at least some intellectual and emotional investment in showing their own hypotheses to be correct.

But to say this study lacks dispassionate objectivity is a colossal understatement. I do have respect for people who investigate fringe phenomena from a scientific standpoint -- the work of the Society for Psychical Research in the UK comes to mind -- but unfortunately, this one ain't it.

So back to the drawing board. I guess I'll have to keep waiting for McConnell's soul to appear and for Carlson to humiliate himself completely in front of millions of viewers. Pity, that.

***************************************

Author Michael Pollan became famous for two books in the early 2000s, The Botany of Desire and The Omnivore's Dilemma, which looked at the complex relationships between humans and the various species that we have domesticated over the past few millennia.

More recently, Pollan has become interested in one particular facet of this relationship -- our use of psychotropic substances, most of which come from plants, to alter our moods and perceptions. In How to Change Your Mind, he considered the promise of psychedelic drugs (such as ketamine and psilocybin) to treat medication-resistant depression; in this week's Skeptophilia book recommendation of the week, This is Your Mind on Plants, he looks at another aspect, which is our strange attitude toward three different plant-produced chemicals: opium, caffeine, and mescaline.

Pollan writes about the long history of our use of these three chemicals, the plants that produce them (poppies, tea and coffee, and the peyote cactus, respectively), and -- most interestingly -- the disparate attitudes of the law toward them. Why, for example, is a brew containing caffeine available for sale with no restrictions, but a brew containing opium a federal crime? (I know the physiological effects differ; but the answer is more complex than that, and has a fascinating and convoluted history.)

Pollan's lucid, engaging writing style places a lens on this long relationship, and considers not only its backstory but how our attitudes have little to do with the reality of what the use of the plants do. It's another chapter in his ongoing study of our relationship to what we put in our bodies -- and how those things change how we think, act, and feel.

[Note: if you purchase this book using the image/link below, part of the proceeds goes to support Skeptophilia!]