One of the most pernicious tendencies in human thought is our arrogance. The attitude that we know all there is to know, understand the universe, have it all figured out, has led to more oversights, blunders, and outright idiocy than anything else I can think of.

What's striking is how often our intuition about things turns out to be wrong. Consider, for example, the following question: of all the species currently alive on Earth, what percent of them are known to science -- identified, observed, collected, or studied?

The best estimate we have, from a 2011 study that appeared in PLoS Biology, blew my mind, and as a 32-year veteran of teaching biology, I was ready for an answer lower than my expectation. You ready?

Fourteen percent.

The study estimated the total number of species on Earth at 8.7 million, 86% of which are unknown to science. This is staggering. We are fooling around with our climate and ecosystems, bulldozing our way through our own living space, and potentially destroying millions of species we didn't even know existed.

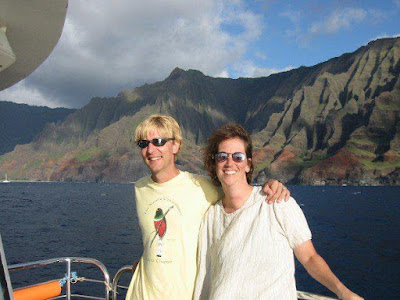

To be fair, our ignorance about the organisms we share the planet with is at least in part not our fault. If, like me, you live in a comfortable home with amenities and no particular need to venture off into the wilderness, it would be easy to think that our familiar surroundings are all there is. The truth is a little humbling, and far more interesting. I remember my first trip to Hawaii, back in 2003, when we spent our time on the lovely island of Kauai. While we were there, we took a boat trip out to the Na Pali Coast, a stunning terrain that has a few narrow sandy beaches, but almost immediately beyond them wrinkles up into mountains that are in places damn near vertical.

The guide on the boat told us something that I found astonishing; large parts of Waimea Canyon and Koke'e Parks, which lie inland from Na Pali, are completely unexplored. Not only is it too steep for roads to be built, you can't even land a helicopter. Hiking might be possible, but it's densely forested. The combination has made the interior of these parks one of the few places in the United States where we can say with fair confidence that no human being has ever stood.

Add to that the fact that even more unexplored than some of the remote terrestrial regions are the deep oceans. I've heard it said we know more about the terrain of the Moon than we do about the floor of the deep ocean -- I don't know if that's true, but it sure sounds plausible.

I'd like to consider, though, a more positive thought; that our lack of knowledge of other species on Earth means there is a lot out there that we could still potentially learn. And sometimes that happens through unexpected channels. In fact, the reason this whole topic comes up is because of an article last week in Atlas Obscura about a British botanist and biological artist named Marianne North (24 October 1830-30 August 1890), who traveled all over the world painting native plants in intricate detail -- and who captured an image of at least one plant nobody could identify.

The painting in question was made in Sarawak, one of two states of Malaysia that are on the island of Borneo. Sarawak is a bit like Kauai; inhabited at the perimeter, but with an inland of rugged terrain and dense, nearly impenetrable forest. Well, this kind of thing didn't stop North, who made some exquisite paintings of plants in Sarawak, including this one:

The plant with the blue berries was unidentified -- some botanists thought it might be a member of the tropical genus Psychotria (in the coffee family, Rubiaceae). But something about that didn't ring true. None of the 1,582 catalogued species of Psychotria has blue berries -- all the known ones are red or pink -- and the arrangement of the leaves didn't look quite right. So either (1) this one was an anomaly, (2) North painted the plant inaccurately, or (3) the identification was wrong.

Option (1) was a little far-fetched, but not outside the realm of possibility. Option (2) struck most knowledgeable people as outright impossible; North was known for her absolute painstaking attention to minute detail. So botanist and illustrator Tianyi Yu decided (3) had to be correct. But how to find a single species of plant in an overgrown wilderness on the island of Borneo, which had avoided detection by other scientists for over a century?

Yu had a brainstorm; maybe it hadn't completely flown under the radar. He decided to spend some time in the herbarium at Kew Gardens. If you are ever in England, Kew is a must-see; it is home to one of the most amazingly complete collection of plants in the world, and is also stunningly beautiful, especially in spring and summer. The herbarium contains collections of preserved plants stretching back to its founding in the middle of the nineteenth century, and currently houses over eight million specimens.

So saying it was a needle in a haystack is an understatement. Yu had one thing going for him; North had been not only a meticulous artist, she was also conscientious about writing down where her paintings had been made. This one was labeled "Matang Forest, Sarawak," and since the Kew specimens are catalogued not only by species but by location, it significantly narrowed down Yu's search.

And he found it. A sprig of it was collected in 1973 and sent back to Kew, but was unidentified. Yu studied both the specimen and North's painting, and concluded that it was a member of the genus Chassalia -- also in Rubiaceae, so the guess of Psychotria hadn't been that far off.

Further analysis by botanists confirmed Yu's surmise. As the person who identified it as a previously-unrecorded species, Yu was given the honor of naming it.

And last year, it went down in the taxonomic records as Chassalia northi, in recognition of Marianne North's contributions to the field of botany.

So out there on the island of Borneo is a little shrub with white flowers and blue berries that we now have a name for because of a nineteenth-century adventurer/scientist/artist, a happenstance collection from 1973, and a diligent modern botanist determined to put the pieces together. Just showing that we can still pick away at the sphere of our own ignorance -- but only if we are first willing to admit that there is a lot we still don't know about the world we live in.

**************************************

%20crop.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment