A couple of days ago, I was talking with my son about the Standard Model of Particle Physics (as one does).

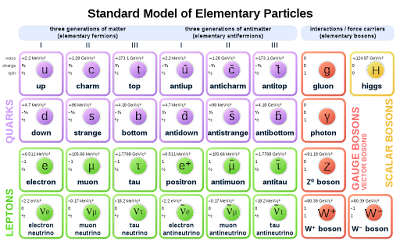

The Standard Model is a theoretical framework that explains what is known about the (extremely) submicroscopic world, including three of the four fundamental forces (electromagnetism, the weak nuclear force, and the strong nuclear force), and classifies all known subatomic particles.

Many particle physicists, however, are strongly of the opinion that the model is flawed. One issue is that one of the four fundamental forces -- gravitation -- has never been successfully incorporated into the model, despite eighty years of the best minds in science trying to do that. The discovery of dark matter and dark energy -- or at least the effects thereof -- is also unaccounted for by the model. Neither does it explain baryon asymmetry, the fact that there is so much more matter than antimatter in the observable universe. Worst of all is that it leaves a lot of the quantities involved -- such as particle masses, relative strengths of forces, and so on -- as empirically-determined rather than proceeding organically from the theoretical underpinnings.

This bothers the absolute hell out of a lot of particle physicists. They have come up with modification after modification to try to introduce new symmetries that would make it seem not quite so... well, arbitrary. It just seems like the most fundamental theory of everything should be a lot more elegant than it is, and that there should be some underlying beautiful mathematical logic to it all. The truth is, the Standard Model is messy.

Every one of those efforts to create a more beautiful and elegant model has failed. Physicist Sabine Hossenfelder, in a brilliant but stinging takedown of the current approach that you really should watch in its entirety, puts it this way: "If you follow news about particle physics, then you know that it comes in three types. It's either that they haven't found that thing they were looking for, or they've come up with something new to look for which they'll later report not having found, or it's something so boring you don't even finish reading the headline." Her opinion is that the entire driving force behind it -- research to try to find a theory based on beautiful mathematics -- is misguided. Maybe the actual universe simply is messy. Maybe a lot of the parameters of physics, such as particle masses and the values of constants, truly are arbitrary (i.e., they don't arise from any deeper theoretical reason; they simply are what they're measured to be, and that's that). In her wonderful book Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray, she describes how this century-long quest to unify physics with some ultra-elegant model has generated very close to nothing in the way of results, and maybe we should accept that the untidy Standard Model is just the way things are.

Because there's one thing that's undeniable: the Standard Model works. In fact, what generated this post (besides the conversation with my science-loving son) is a paper that appeared last week in Physical Review Letters about a set of experiments showing that the most recent tests of the Standard Model passed with a precision that beggars belief -- in this case, a measurement of the electron's magnetic moment which agreed with the predicted value to within 0.1 billionths of a percent.

This puts the Standard Model in the category of being one of the most thoroughly-tested and stunningly accurate models not only in all of physics, but in all of science. As mind-blowingly bizarre as quantum mechanics is, there's no doubt that it has passed enough tests that in just about any other field, the experimenters and the theoreticians would be high-fiving each other and heading off to the pub for a celebratory pint of beer. Instead, they keep at it, because so many of them feel that despite the unqualified successes of the Standard Model, there's something deeply unsatisfactory about it. Hossenfelder explains that this is a completely wrong-headed approach; that real discoveries in the field were made when there was some necessary modification of the model that needed to be made, not just because you think the model isn't pretty enough:

If you look at past predictions in the foundations of physics which turned out to be correct, and which did not simply confirm an existing theory, you find it was those that made a necessary change to the theory. The Higgs boson, for example, is necessary to make the Standard Model work. Antiparticles, predicted by Dirac, are necessary to make quantum mechanics compatible with special relativity. Neutrinos were necessary to explain observation [of beta radioactive decay]. Three generations of quarks were necessary to explain C-P violation. And so on... A good strategy is to focus on those changes that resolve an inconsistency with data, or an internal inconsistency.And the truth is, when the model you already have is predicting with an accuracy of 0.1 billionths of a percent, there just aren't a lot of inconsistencies there to resolve.

I have to admit that I get the particle physicists' yearning for something deeper. John Keats's famous line, "Beauty is truth, and truth beauty; that is all ye know on Earth, and all ye need to know" has a real resonance for me. But at the same time, it's hard to argue Hossenfelder's logic.

Maybe the cosmos really is kind of a mess, with lots of arbitrary parameters and empirically-determined constants. We may not like it, but as I've observed before, the universe is under no obligation to be structured in such a way as to make us comfortable. Or, as my grandma put it -- more simply, but no less accurately -- "I've found that wishin' don't make it so."