Today's topic falls into the category of "The More You Think About It, The Weirder It Gets," and comes to us courtesy of my writer friend Andrew Butters.

Before I get to the meat and potatoes of the story, two bits of background.

Auroras occur because of the solar wind, a powerful stream of particles (chiefly electrons and protons) emitted from the upper atmosphere of the Sun. When they strike the Earth's upper atmosphere and interact with the various molecules in the air, this has the effect of exciting the electrons in the molecules (bouncing them to higher energy levels), and when those electrons fall back into the ground state, they emit the extra energy as light. Because of the quantization of energy levels, each color (frequency) is associated with a particular transition in a particular element -- the commonest are reds and greens (from oxygen) and blues (from nitrogen).

Auroras on Earth are most often seen in high latitudes because of the shape of the Earth's magnetic field. The slope of the magnetic field lines increases the closer you get to the poles, so at high latitudes it acts a bit like a funnel, creating spectacular displays in the Arctic and Antarctic regions.

Despite the fact that I feel like I feel like I live in the Frozen North (especially at this time of year), I've only ever gotten to see the auroras once. It was about ten years ago, and we heard there was a solar storm and the "Northern Lights" were going to be seen a lot farther south than usual. That night it was supposed to be crystal-clear -- also an unusual occurrence in this cloudy climate -- so once it was dark, my wife and I went across the street into the neighbor's field and watched for a while, with disappointing results of the "Is that a flicker? I think that's a flicker" sort.

At some point my wife, who is clearly the brains of the operation, realized that we were looking for the Northern Lights, but we were facing south. In our defense, there were fewer trees obstructing the sky in that direction, but it's still a little like the guy who was searching around the kitchen floor for his contact lens, and his wife joined him, but the two of them couldn't find it. She finally said, "Are you sure you dropped it in the kitchen?" And he responded, "No, I dropped it in the bathroom, but the light is better in here."

In any case, we turned around to the north...

.... and wow.

Over our rooftop and beyond the branches of the walnut trees was a light show like I've never seen before -- shifting curtains of green luminescence resembling some kind of gauzy emerald curtain. It was spectacular. We watched it for about forty-five minutes before it finally started to fade.

So if you're ever looking for auroras, make sure you're pointed the right way.

The second piece of background is that there is a strange astronomical object called a brown dwarf. Brown dwarfs are almost-stars -- something on the order of twenty to eighty times the mass of the planet Jupiter. Since the fusion of hydrogen into helium -- what powers stars' cores -- requires intense pressure to get started, there's a lower limit to the mass a star can have. Below that mass, the gravity of its contents is insufficient to raise the pressure in the core to the point where fusion can begin, and what you end up with is something midway between a planet and a star.

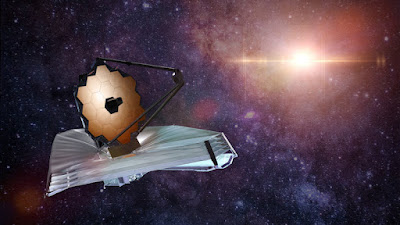

Well, the link Andrew sent me is about a new discovery by the amazing James Webb Space Telescope -- of a brown dwarf, W1935, which has auroras.

On first glance, you might think, "why not?" But remember how auroras are created. They're caused by the interaction of a stream of high-energy particles with the atmosphere of a planet.

So where are the high-energy particles coming from?

Even odder, the atmosphere of W1935 seems to have a temperature inversion -- a region of the atmosphere that warms, rather than cools, with increasing altitude. Its upper atmosphere was glowing with the very specific infrared frequency given off when you heat methane. So not only does it have auroras when there's no reason it should, there's some sort of a heat source that's creating convection in its atmosphere without it receiving an external heat input from a star.

"We expected to see methane, because methane is all over these brown dwarfs. But instead of absorbing light, we saw just the opposite: The methane was glowing," said Jackie Faherty, of the American Museum of Natural History, who led the study. "My first thought was, what the heck? Why is methane emission coming out of this object?... With W1935, we now have a spectacular extension of a solar system phenomenon without any stellar irradiation to help in the explanation. With the JWST, we can really 'open the hood' on the chemistry and unpack how similar or different the auroral process may be beyond our solar system."****************************************

|