I can think of no more terrifying disorder than locked-in syndrome.

Locked-in syndrome, also called a pseudocoma or cerebromedullospinal disconnection, is a (fortunately) rare condition where the entire voluntary muscle system shuts down but leaves the cognitive facilities relatively intact. The result: you can't move, speak, or respond, but your brain is otherwise functioning normally.

You are a prisoner inside your own useless body.

The most famous case of locked-in syndrome was French journalist Jean-Dominique Bauby, who suffered a massive stroke at age 43 and lost control of his entire muscular system except for partial control over his left eye. This at least allowed him to eventually communicate to his doctors that he was still conscious, and -- astonishingly -- he used that tiny bit of voluntary muscular movement to direct a cursor on a computer screen and painstakingly, letter by letter, write a book about his experience. It's called The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, and it is simultaneously devastating and uplifting -- a paean to the human spirit's ability to rise above a level of adversity that, thankfully, very few of us will ever face.

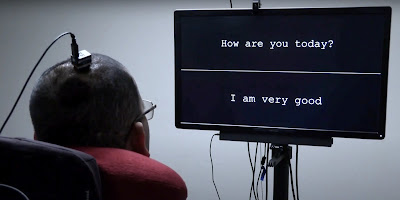

Thanks to an article last week in IEEE Spectrum, I just found out about a new prosthetic device that will give people who have lost their ability to communicate their voices back -- by converting their brain waves into words.

A team at the University of California - San Francisco has done (successful) clinical trials of a device that is implanted through a small port in the patient's skull, and is able to detect the neural signals the cerebellum and motor cortex send to the patient's larynx and mouth when they think about speaking. From the encoded electric impulses representing the movements the person would have made, had they been able to speak, the prosthesis is able to produce whole sentences of text -- at eighteen words a minute.

Pretty impressive, especially considering that this was just proof-of-concept, so as the technology is refined, it'll only get better. And considering that Bauby was communicating at two to three letters per minute, this is an incredible leap forward.

"We’re now pushing to expand to a broader vocabulary," said Edward Chang, who led the team that developed the prosthesis. "To make that work, we need to continue to improve the current algorithms and interfaces, but I am confident those improvements will happen in the coming months and years. Now that the proof of principle has been established, the goal is optimization. We can focus on making our system faster, more accurate, and—most important— safer and more reliable. Things should move quickly now."

No comments:

Post a Comment