A couple of months ago, I wrote a post about the brilliant and tragic British mathematician, cryptographer, and computer scientist Alan Turing, in which I mentioned in passing the halting problem. The idea of the halting problem is simple enough; it's the question of whether a computer program designed to determine the truth or falsity of a mathematical theorem will always be able to reach a definitive answer in a finite number of steps. The answer, surprisingly, is a resounding no. You can't guarantee that a truth-testing program will ever reach an answer, even about matters as seemingly cut-and-dried as math. But it took someone of Turing's caliber to prove it -- in a paper mathematician Avi Wigderson called "easily the most influential math paper in history."

What's the most curious about this result is that you don't even need to understand fancy mathematics to find problems that have defied attempts at proof. There are dozens of relatively simple conjectures for which the truth or falsity is not known, and what's more, Turing's result showed that for at least some of them, there may be no way to know.

One of these is the Collatz conjecture, named after German mathematician Lothar Collatz, who proposed it in 1937. It's so simple to state that a bright sixth-grader could understand it. It goes like this:

Start with any positive integer you want. If it's even, divide it by two. If it's odd, multiply it by three and add one. Repeat. Here's a Collatz sequence, starting with the number seven:

7, 22, 11, 34, 17, 52, 26, 13, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.

Collatz's conjecture is that if you do this for every positive integer, eventually you'll always reach one.

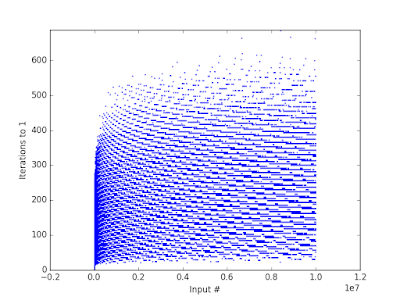

The problem is, the procedure involves a rule that reduces the number you've got (n/2) and one that grows it (3n + 1). The sequence rises and falls in an apparently unpredictable way. For some numbers, the sequence soars into the stratosphere; starting with n = 27, you end up at 9,232 before it finally hits a number that allows it to descend to one. But the weirdness doesn't end there. Mathematicians studying this maddening problem have made a graph of all the numbers between one and ten million (on the x axis) against the number of steps it takes to reach one (on the y axis), and the following bizarre pattern emerged:

So it sure as hell looks like there's a pattern to it, that it isn't simply random. But it hasn't gotten them any closer to figuring out if all numbers eventually descend to one -- or if, perhaps, there's some number out there that just keeps rising forever. All the numbers tested eventually descend, but attempts to figure out if there are any exceptions have failed.

Despite the fact that in order to understand it, all you have to be able to do is add, multiply, and divide, American mathematician Jeffrey Lagarias lamented that the Collatz conjecture "is an extraordinarily difficult problem, completely out of reach of present-day mathematics."

Another theorem that has defied solution is the Goldbach conjecture, named after German mathematician Christian Goldbach, who proposed it to none other than mathematical great Leonhard Euler. The Goldbach conjecture is even easier to state:

All positive integers greater than two can be expressed as the sum of two prime numbers.

It's easy enough to see that the first few work:

3 = 1 + 2

4 = 1 + 3

5 = 2 + 3

6 = 3 + 3 (or 1 + 5)

7 = 2 + 5

8 = 3 + 5

and so on.

But as with Collatz, showing that it works for the first few numbers doesn't prove that it works for every number, and despite nearly three centuries of efforts (Goldbach came up with it in 1742), no one's been able to prove or disprove it. They've actually brute-force tested all numbers between 3 and 4,000,000,000,000,000,000 -- I'm not making that up -- and they've all worked.

But a general proof has eluded the best mathematical minds for close to three hundred years.

The bigger problem, of course, is that Turing's result shows that not only do we not know the answer to problems like these, there may be no way to know. Somehow, this flies in the face of how we usually think about math, doesn't it? The way most of us are taught to think about the subject, it seems like the ultimate realm in which there are always definitive answers.

But here, even two simple-to-state conjectures have proven impossible to solve. At least so far. We've seen hitherto intractable problems finally reach closure -- the four-color map theorem comes to mind -- so it may be that someone will eventually solve Collatz and Goldbach.

Or maybe -- as Turing suggested -- the search for a proof will never halt.

****************************************