Back in 1859, renowned British naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace wrote a paper about a peculiar phenomenon, which has since been called Wallace's Line in his honor. He had noted that west of a wavering line that runs basically from northeast to southwest across Indonesia, the flora and fauna is much more similar to what you find in India and tropical southeast Asia; east of that line, it resembles what you find in Australia and Papua-New Guinea.

The change is striking enough that it didn't take a naturalist of Wallace's caliber to notice it. Italian explorer Antonia Pigafetta mentioned it in his journals way back in 1521, and various others considered it a curiosity worth noting. None, though, did the thorough job of studying it that Wallace did, so naming it after him is justified.

However -- even Wallace had no idea why, or how, it had happened.

Ordinarily, faunal and floral assemblages change gradually, unless there's a major geographical barrier. I saw an example of the latter first-hand when I was in Ecuador -- there's a completely different set of birds as you cross from the west slope to the east slope of the Andes Mountains. (Some did make the leap, but by and large, you run into a whole different group of species from one side to the other.)

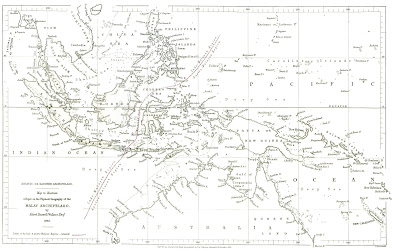

Here, though, there's no obvious barrier. In fact, if you'll look closely at the map, you'll see that Wallace's Line goes right between the islands of Bali (on the west) and Lombok (on the east) -- a distance of only 35 kilometers, easily narrow enough for birds to cross, not to mention other species swimming or rafting their way from one island to the other. Even so, the species on Bali are distinctly Asian, and the ones on Lombok distinctly Australian.

On one side, kangaroos and koalas, cockatoos and birds of paradise and cassowaries; on the other, bears and tigers, trogons and drongos and minivets and babblers.

How did this happen -- and more perplexingly, what's kept the line intact?

The explanation for the first part of this question had to wait until the discovery of plate tectonics in the 1950s. The Australian region and Asia have very different species because they are on different tectonic plates that used to be a great deal farther away from each other; in fact, until 85 million years ago, Australia was connected to Antarctica (something we know not only from our understanding of plate movement, but because prior to that Australia and Antarctica have similar fossils, which began to diverge at that point as Australia moved north and Antarctica moved south). Australia has been gradually approaching Asia ever since, with its unique assemblage of species riding in like some latter-day Noah's Ark.

What, though, is keeping them from mixing? The reason the topic comes up today is because of a paper last week in Science that has proposed a neat explanation; the problem is the climate.

Researchers at ETH-Zürich led by evolutionary biologist Loïc Pellissier noted that there were exceptions to the boundary of Wallace's line, but the species that crossed it almost always went one way -- from the Asian region into the Australian region. Some species of Australian snakes, for example, have their nearest relatives in Asia, as do the wonderful Australian flying foxes. But there are virtually no examples of species that went the other way.

What was preventing organisms from island-hopping their way from Australia to Asia was Asia's much wetter climate -- if you go from west to east across Indonesia and into Australia, the average rainfall by and large goes steadily downward. The contention is that it's easier for organisms from a rainy climate to adapt to gradually drying out than it is for extremely dry-adapted organisms to deal with the already high biodiversity (and thus much higher competition with species already well suited to the conditions) found in more rainy regions.

You have to wonder what will happen when Australia and Asia finally collide -- something that is, in a sense, already happening, but will result in a complete fusion of the two continents in two hundred million years or so. This will result in a situation a little like the collision of India with Asia eighty million years ago, which raised the Himalaya Mountains. (In fact, that collision is ongoing; as India pushes north, like a giant plow, the Himalayas are continuing to rise. Which is why you find marine fossils at the top of Mount Everest -- the Himalayas aren't volcanic, they're marine and continental debris scooped together and piled up by the motion of India.)

The collision of Australia and Asia will, of course, eradicate Wallace's Line (although the mountain range it will create could still provide a barrier for species mixing, just as the Andes do in Ecuador and Peru). Of course, two hundred million years is a very long time -- about three times as long as it's been since the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs -- so who knows what species will have evolved in the interim?

Or if we'll have any distant descendants of our own around to see it?

****************************************