In the wonderful Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Tapestry," Captain Picard's life is in danger because an accident damaged his artificial heart. He'd received the biomechanical prosthesis decades earlier, because his original heart was irreparably damaged in a fight he got in when he was a young, cocky student at Starfleet Academy. The inimitable Q offers Picard a choice -- to go back in time and change the circumstances that led to the fight -- meaning he'd have his own original heart, and the accident wouldn't lead to his death. But, as such stories usually go, Picard finds out that rectifying one mistake doesn't necessarily lead to his life having a better trajectory -- and that perhaps a shorter, richer life, facing risks head-on, is better than one that lasts longer because of always playing it safe.

But what if someone who needed a heart could have one grown from the person's own cells?

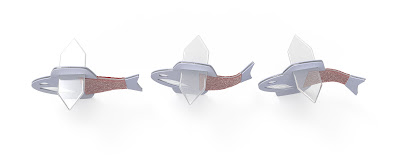

That's where a fascinating bit of research out of the University of Harvard is pointing. In a paper published in Science this week, a team led by Keel Yong Lee showed proof-of concept -- by creating an artificial fish made of human heart stem cells.

The "biohybrid" was made by creating a finely-grooved, two-sided scaffolding on which were laid cardiac cells. The cells aligned themselves with the grooves, growing into a pair of parallel sheets. Grafted onto this was an autonomous pacing node -- a little like the heart's pacemaker -- which stimulated rhythmic contractions on opposite sides, allowing the "fish" to swim. Best of all, as the cells matured, the fish got better and better at swimming, eventually reaching speeds and maneuverability comparable to a zebrafish, the species the biohybrid was modeled on.

"Our ultimate goal is to build an artificial heart to replace a malformed heart in a child," said Kit Parker, who was senior author of the paper, in a press release. "Most of the work in building heart tissue or hearts, including some work we have done, is focused on replicating the anatomical features or replicating the simple beating of the heart in the engineered tissues. But here, we are drawing design inspiration from the biophysics of the heart, which is harder to do. Now, rather than using heart imaging as a blueprint, we are identifying the key biophysical principles that make the heart work, using them as design criteria, and replicating them in a system, a living, swimming fish, where it is much easier to see if we are successful."We are nearing the point where faulty organs in our bodies can simply be replaced by biomechanical devices, not so far away from Jean-Luc Picard's heart. This would obviate the nerve-wracking trauma of waiting an indefinite amount of time for a donor, and also the potential for tissue compatibility issues, as the organ would be built out of your own cells.

We're still a ways out, though. The Lee et al. research demonstrates that it's possible to build functional, coordinated contractile tissue -- the first step in generating a working heart -- and, as we've seen so many times before, it's often an amazingly short time between showing that something is theoretically possible and its becoming a reality.

So once again, Star Trek has shown itself to be prescient. I hope this keeps happening -- communicators (the ones in the original series even looked like flip-phones), voice-activated software, translation programs, and videoconferincing all appeared on Star Trek long before they became household items. Now, I wish the scientists would get to work on transporters, replicators, and the holodeck. Because those would be all kinds of cool, especially the holodeck, although I'd stand a significant chance of finding a program I liked better than reality and disappearing permanently.

*********************************

This week's Skeptophilia book-of-the-week combines cutting-edge astrophysics and cosmology with razor-sharp social commentary, challenging our knowledge of science and the edifice of scientific research itself: Chanda Prescod-Weinsten's The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred.

Prescod-Weinsten is a groundbreaker; she's a theoretical cosmologist, and the first Black woman to achieve a tenure-track position in the field (at the University of New Hampshire). Her book -- indeed, her whole career -- is born from a deep love of the mysteries of the night sky, but along the way she has had to get past roadblocks that were set in front of her based only on her gender and race. The Disordered Cosmos is both a tribute to the science she loves and a challenge to the establishment to do better -- to face head on the centuries-long horrible waste of talent and energy of anyone not a straight White male.

It's a powerful book, and should be on the to-read list for anyone interested in astronomy or the human side of science, or (hopefully) both. And watch for Prescod-Weinsten's name in the science news. Her powerful voice is one we'll be hearing a lot more from.

[Note: if you purchase this book using the image/link below, part of the proceeds goes to support Skeptophilia!]