I've been interested in the occult since I was a teenager. It started when I was about fifteen, on one of the annual trips with my dad to Arizona and New Mexico (mostly for hiking and rockhounding, as my father was a lapidary and avid rock collector), and stumbled upon a funky little old used bookstore in the town of Alpine, Texas. It was there I picked up a book called The Black Arts: A History of Occult Practice by Richard Cavendish, which I devoured (and, incidentally, I still own).

I started collecting Tarot decks (again, which I still own) and other objets de magique, not to mention reading voraciously other books on the occult. By the time I was in my upper teens I'd already begun to admit to myself that it was all rather ridiculous, but -- to paraphrase the famous poster on Fox Mulder's office wall in The X Files -- dammit, I wanted to believe.

There was a time while I was in college when my attraction for magical thinking did serious war with my training in skeptical, rational hard science, but eventually I had to admit that -- as far as I'd seen -- occult practice stumbles hard over one fact; it simply doesn't work. There's never been a single rigorous test of magical claims in which the claim has proven to be valid. It hasn't stopped people from believing in it all, of course. I can attest that even despite my skepticism, I'm still drawn to it. It's undoubtedly why I write paranormal fiction; it allows me to exercise, or perhaps exorcise, some very deep-seated desires about the way I'd like the world to work.

Of course, I should interject here that the fact that it hasn't been validated yet doesn't mean it never will. As I've said many times before about such matters as ghosts and the afterlife and cryptids, all I'd need is scientifically admissible hard evidence, and I'd have no choice but to change my mind. But from my perspective, the times people have actually tried to do the occult have always devolved into something fruitless, silly, and... well... a bit banal.

And that brings us to the Battle of Blythe Road.

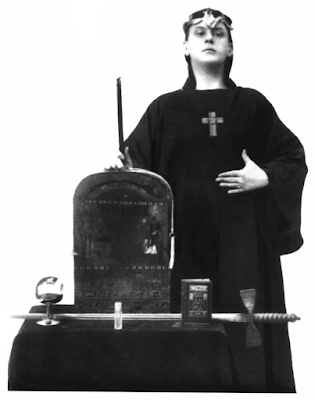

All of you will undoubtedly recognize the names of the major players in this calamitous non-event. First, there was Irish poet W. B. Yeats; second, Samuel Liddell "MacGregor" Mathers (he added the "MacGregor" part because he was a Celtophile and didn't much like his solidly English-sounding given names); and finally, Aleister Crowley, British occultist and writer and self-styled "Wickedest Man in the World."

The backdrop of all this is an occult organization called the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, founded and ruled with an iron fist by Mathers, which held its meetings in a building on Blythe Road in London. The Order had three levels; the lowest was initiatory, and involved study of esoteric philosophy including the Qabalah and other occult writings. The second was where the good stuff started; once in the second order, you learned alchemy, astral projection, divination, and geomancy, and also (by some accounts) got to participate in some pretty hot-sounding sex rituals. The third order was only for the crème de la crème, i.e., the people MacGregor Mathers liked. It had a great many influential members -- not only the ones I've mentioned, but such luminaries as Algernon Blackwood, Bram Stoker, and Arthur Machen.

The trouble started when Aleister Crowley, who was in the lowest order, demanded to be initiated into the second. Yeats, who was quite influential in the Order of the Golden Dawn, spoke out very forcefully against Crowley's being allowed to take the step up. Yeats and Crowley had hated each other pretty much from the get-go; a lot of it apparently stemmed from Yeats criticizing Crowley's poetry, something the latter did not accept lightly. Yeats, on the other hand, was concerned with more than just literary output. He took seriously Crowley's penchant for controlling and threatening people, not to mention his habit of having sex with anyone of either gender who would hold still long enough, and told some of the higher-ups that he was concerned that if Crowley learned the secrets of the second order, he'd use them for evil purposes.

So the leaders -- notably, not including Mathers -- told Crowley no deal.

Crowley, predictably, didn't take that well either. He went to complain to Mathers, who was in Paris at the time, and Mathers sided with Crowley. He did a solo initiation of Crowley into the second order, and gave him instructions for some spells to use against Yeats and his cronies. Thus armed, Crowley came to the Golden Dawn headquarters on Blythe Road to open a can of magical whoopass.

What happened was nothing short of comical. Crowley walked up the stairs, thundering the magic spells he'd learned from Mathers. Yeats et al. were waiting for him at the top of the stairs. When he was in range, Yeats simply kicked Crowley until he lost his balance and fell down the stairs.

And thus ended the Battle of Blythe Road.

Crowley retreated in disarray, but recall that he was not a man to admit defeat, and he decided to take revenge on Yeats (magically, of course). He seduced the Irish artist Althea Gyles and asked her for help casting some spells on Yeats, but Gyles (for reasons unknown, but possibly related to the fact that Crowley was a skeevy sonofabitch) double-crossed him by snipping off a lock of his hair while he was asleep and sending it to Yeats, so the latter could come up with some Crowley-specific counter-spells. So Crowley's second attempt to kick ass and take names also failed.

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn never quite recovered from the infighting. It splintered into bunches of schismatic offspring, such that at one point there were more secret occult esoteric orders in Britain than there were actual secret occult esotericists. But what strikes me is that despite all this, the members still seemed to treat their practices with such infernal gravity that the whole situation began to resemble a bunch of little kids playing some kind of super serious game of Let's Pretend. This, despite the fact that everyone knew that three of the most accomplished adepts -- Yeats, Mathers, and Crowley -- had a massive magical duel that was settled when one of them kicked another one down the stairs.

So anyhow, that's the story of the Battle of Blythe Road. Like I said before, I would love it if I could report that there was all of this occult stuff done, à la Harry Potter dueling Voldemort, and sparks flew and crazy magic shit happened until the evil guy was vanquished by a powerful spell. But as my grandma used to tell me, wishin' don't make it so. More's the pity, because it sure would be fun to live in a world where Tarot decks told you the future and magic wands really worked.