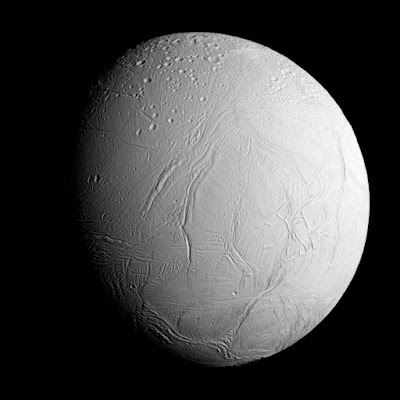

Last week, I wrote a piece on the peculiarities of Jupiter's moon Io -- surely one of the most inhospitable places in the Solar System, with hundreds of active volcanoes, lakes of liquid sulfur, and next to no atmosphere. But there's a place even farther out from the warmth of the Sun that is one of our best candidates for an inhabited world -- and that's Saturn's icy moon Enceladus.

It's the sixth largest of Saturn's eighty-some-odd moons, and was discovered back in 1789 by astronomer William Herschel. Little was known about it -- it appeared to be a single point of light in telescopes -- until the flybys of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 in 1980 and 1981, respectively, and even more was learned by the close pass in 2005 by the Cassini spacecraft.

Enceladus, like Io, is an active world. It has a thick crust mostly made of water ice, but there are "cryovolcanoes" -- basically enormous geysers -- that jet an estimated two hundred kilograms of water upward per second. Some of it falls back to the surface as snow, but the rest is the primary contributor to Saturn's E ring,

Where it gets even more interesting is that beneath the icy crust, there is an ocean of liquid water estimated to be ten kilometers deep (just a little shy of the depth of the Marianas Trench, the deepest spot in Earth's oceans). Like Io's wild tectonic activity, the geysers of Enceladus are maintained primarily by tidal forces exerted by its host planet and the other moons. But that's where any resemblance to Io ends. Chemically, it could hardly be more different. Analysis of the snow ejected by the cryovolcanoes of Enceladus found that dissolved in the water was ordinary salt (sodium chloride), with smaller amounts of ammonia, carbon dioxide, methane, sulfur dioxide, formaldehyde, and benzene.

What jumped out at scientists about this list is that these compounds contain just about everything you need to build the complex organic chemistry of a cell -- carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, and sulfur. I say "just about" because one was missing, and it's an important one: phosphorus. In life on Earth, phosphorus has two critical functions -- it forms the "linkers" that hold together the backbones of DNA and RNA, and it is part of the carrier group for energy transfer in the ubiquitous compound ATP. (In vertebrates, it's also a vital part of our endoskeletons, but that's a more restricted function in a small subgroup of species.)

But just last month, a paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union describing the research that finally found the missing ingredient. There is phosphorus in Enceladus's ocean -- in fact, it seems to have a concentration thousands of times higher than in the oceans of Earth.

This is eye-opening because phosphorus is a nutrient that is rather hard to move around, as vegetable gardeners know. If you buy commercial fertilizer, you'll find three numbers on the package separated by hyphens, the "N-P-K number" representing the percentage by mass of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, respectively. These three are often the "limiting nutrients" for plant growth -- the three necessary macronutrients that many soils lack in sufficient quantities to grow healthy crops. And while the nitrogen and potassium components usually (depending on the formulation) "water in" when it rains and spread around to the roots of your vegetable plants, phosphorus is poorly soluble and tends to stay pretty much where you put it.

The fact that the snow on Enceladus has amounts of phosphorus a thousand times higher than the oceans of Earth must mean there is lots down there underneath the ice sheets.

This strongly boosts the likelihood that there's life down there as well. Primitive life, undoubtedly; it's unlikely there are Enceladian whales swimming around under the ice. But given how quickly microbial life evolved on Earth after its surface cooled and the oceans formed, I feel in my bones that there must be living things on Enceladus, given the fact that all the ingredients are there. (The oceans on Earth formed on the order of 4.5 billion years ago, and the earliest life is likely to have begun on the order of four billion years ago; given a complete recipe of materials and an energy source, complex biochemistry seems to self-assemble with the greatest of ease.)

Maybe I'm being overly optimistic, but the discovery of phosphorus in the snows of Enceladus makes me even more certain that extraterrestrial life exists, and must be common in the universe. If we can show that there are living things down there, on a mostly frozen moon 1.4 billion kilometers from the Sun, then it will show that life can occur almost anywhere -- as long as you have all the ingredients for the recipe.