My older son has followed in his old man's footsteps, combining a fascination for astronomy, biology, chemistry, and physics with a wild imagination to generate a fantastic universe within which to spin fictional tales. He is adding a skill I most definitely do not have -- art -- to create a brain-bending saga that I'm sure you will one day see sitting on people's bookshelves.

Just a couple of days ago, we were talking his creation, and were musing about the possibility of alien intelligence, and in particular, the fact that the kind of intelligence we humans evolved was very much driven by the kind of planet we live on. The tools we create, which facilitated our dominance of the Earth, required availability of metal ores and the ability to make fire to smelt them. Even our combative, competitive nature may well owe its origins to our having evolved in a place (east Africa) with plentiful large predators, scarce resources, and seasonal drought.

What kind of intelligence might develop on a planet with no dry land? That intelligence can develop in aquatic life forms is undeniable; by most biologists' estimates whales and dolphins have about the same intelligence as the great apes, and at least some of the vocalizations they make might qualify as actual language. (That question is currently not settled, but there have been some suggestive recent studies supporting that contention.)

But even though whales and dolphins are intelligent, they're non-technological. It's entirely imaginable that there could be aquatic life forms that might exceed humans in memory storage, recall, complexity of communication, and flexible problem-solving, and yet they still might not have anything we would call hard technology. Note that the water-world in the Star Wars universe -- Kamino, the origin of the eponymous clones of the Clone Wars -- still had to have a solid (if floating) surface, made of conventional materials like metals, glasses, and plastics, in order to have a technology similar enough to that in the rest of the canon for the story to be plausible.

It all comes down to how much the evolution of intelligent life is constrained -- hemmed in by drivers that would likely generate similar forms in all conceivable habitable worlds. My conclusion is that there are constraints, but they're few in number -- things like having complex sensory organs, having those organs and the central processing unit (brain) located near the anterior end, having some kind of appendages for moving through whatever medium the planet is outfitted with, and having some mechanism for communicating between individuals. That's about it. Otherwise... all bets are off as to what we'll find when we first set foot on another planet.

This significantly complicates the possibility of finding intelligent extraterrestrial life. There could be a water-world populated by something like super-intelligent dolphins, and they would have no capacity for (nor, likely, any interest in) building radio transmitters and receivers. So to us, such a planet would appear completely silent and devoid of life. Our SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) efforts have been confined by necessity to looking for signals of the kind we ourselves send -- which might also restrict us to finding only the life that evolved on planets with conditions extremely similar to Earth.

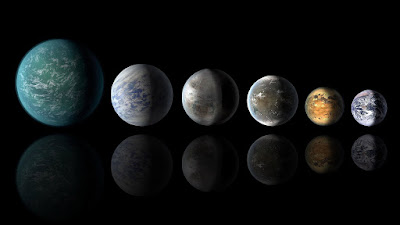

The result is that we might well miss most of what's out there. The reason this comes up -- besides my conversation a couple of days ago with Lucas -- is an article by University of Arizona astronomer Chris Impey that just appeared in The Conversation. Impey tells us something that should encourage people like me, who would very much like it if extraterrestrial life exists out there somewhere; that a third of all exoplanets are "super Earths," planets with a mass between that of the Earth and Neptune. Further, most of these orbit cool dwarf stars, which have a vastly longer life span than Main Sequence stars like the Sun, so there would be a great deal longer for life to evolve and become complex. Impey says that the "most habitable of all possible worlds" would fall into the super Earth category -- roughly twice the mass of Earth, and twenty to thirty percent larger in volume. (The reason is that a larger planet would have a thicker atmosphere with a greater heat-storage capacity, and thus be more resistant to the rapid changes in climate that have plagued the Earth since its formation.)

However, if that thicker atmosphere contained water vapor, you might well be looking at planets completely covered by a deep ocean -- a water-world, where any life would evolve along very different pathways that it has here. In that case, the only way to see that it exists from our perspective here on Earth is by biosignatures, gases in the atmosphere that would be unlikely to exist unless there were life present to create them. (An example is free oxygen in Earth's atmosphere; it's so reactive that without photosynthesizers like plants and phytoplankton producing it continuously, it would get locked up by chemical reactions and disappear from the atmosphere entirely.)

So despite what you might have seen on Star Trek, the most common intelligent alien life out there might not be bipedal humanoids with rubber facial prostheses. We smart hairless apes might actually be vastly in the minority -- a possibility I find fascinating but a little mind-boggling.