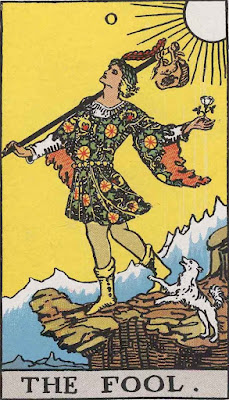

"In the digital age the convergence of ancient wisdom and cutting-edge technology has given rise to new possibilities," writes Jerry Lawton. "One such innovation is AI Tarot reading where the age-old practice of Tarot cards meets the power of artificial intelligence... Through natural language processing and data analysis AI algorithms aim to mimic the intuition and insight traditionally associated with human Tarot readers. This fusion of technology and divination opens up new possibilities for individuals seeking guidance and self-reflection. AI Tarot reading brings the wisdom of Tarot cards to your fingertips anytime and anywhere. With just a few clicks you can access Tarot readings from the comfort of your own home or even on the go. Digital platforms and mobile applications make it easy for individuals to receive instant guidance and insights eliminating the need for in-person consultations. AI algorithms follow a set of predefined rules and principles providing objective interpretations of Tarot cards. These algorithms analyze vast amounts of data, taking into account various factors and symbolism associated with each card. By eliminating subjective biases AI Tarot readings offer consistent and reliable insights that remain unaffected by human emotions or preconceptions."

The cards show that you are now in a period favorable to personal development. This idea of getting better is highlighted by the cards you have selected which show that at work, and in your personal projects, you are adopting a new attitude and a new way of looking at things. Nowadays you tend to think more about the consequences of your acts; there is no question of doing things at random, and making the same mistakes as in the past. This new dynamic opens many doors that go beyond your personal projects.

That's good to hear. I do feel that repeating mistakes from the past is a bad idea, which is why I have a lifelong commitment to making all new and different mistakes.

A proposal will be made that will surprise you for two reasons. First because of the person who will do it: you didn't expect that from her. Then by the proposal itself, which will be just for you and which will be totally unexpected. It will make you very happy, and you will be overwhelmed to be the subject of this proposal. "The innocent will have their hands full", as they say! Innocent because you were not expecting this. Hands full because it will fill you with joy.

Then it's up to you to think about the consequences of this request: to accept? to refuse? It's up to you. Whatever happens, you'll have to give an answer. Take the time to think, because the answer you give will engage you for months in a pattern that you will not be able to get out of easily.

Huh. If the proposal is to turn my upcoming book release into a blockbuster movie, I'm all for it. But the decision-making part worries me a tad. It's never been my forte. In fact, I've often wondered if I have some Elvish blood, given Tolkien's quip, "Go not to the Elves for advice, for they will say both yes and no."

You need calm and tranquility at the moment. You have been tried by long-lasting problems that never seem to get better, it plays on your morale and your daily life goes by so quickly you never seem to get a grip on it. You must have patience, create a bit of distance from a system that is going too quickly for you, and get some perspective on your situation. The card shows a character whose head is buried in the present, trapped by the rhythm of their life, unable to escape.

Well, once again, patience has never been one of my strengths. So this is accurate enough with regards to my personality, but at the same time I'm struck by how generally unhelpful it is. "You need to be more patient, so develop some patience! Now!" doesn't seem like a very good way to approach the problem.

Not, honestly, that I have any better ideas. Unsurprising, I suppose, given that "my head is buried in the present."

What stands out about all this is how generic my reading is. That's how it works, of course; you may remember James Randi's famous demonstration of that principle in a high school classroom, where students were told that a detailed horoscope had been drawn up for them using their birthdates, and they were asked to rate how accurate it seemed for themselves personally on a scale of zero to ten. Just about everyone rated it above seven, and there were loads of nines and tens.

Then they were asked to trade horoscopes with the person next to them... and that's when they found out they were all given the exactly same horoscope.

We're very good at reading ourselves into things, especially when we've been told that whatever it is has been created Especially For Us. Add to that a nice dollop of confirmation bias, and you've got the recipe for belief.

Of course, maybe my overall dubious response was because I chose the no-strings-attached El Cheapo psychic reading. You get what you pay for, or (in this case) didn't pay for.

In any case, I suppose it was just a matter of time that the AI chatbot thing got hybridized with psychic readings. What I wonder is what's going to happen when the AI starts to "hallucinate" -- the phenomenon where AI interfaces have slipped from giving more-or-less correct answers to just making shit up. You pay your money, and instead of a real psychic reading, all you get is some AI yammering random nonsense at you.

That, of course, brings up the question of how you could tell the difference.

****************************************

_4.jpg)