The moral of this short story is either "Don't judge a book by its cover" or "Be careful who you piss off." Both of them seem like decent takeaways.

***************************************

Bad Blood

Melba Crane looked up as Dr. Carlisle entered the room. She smiled, revealing a row of straight, white, and undoubtedly false teeth. “Hello, doctor! I don’t think we’ve met yet. How are you today?”

Dorian Carlisle looked at his new patient. She was tiny, frail-looking, with carefully-styled curly hair of a pure snowy white, and eyes the color of faded cornflowers. “I’m fine, Mrs. Crane. I’m Dr. Carlisle—I’m looking after Dr. Kelly’s patients while he’s on vacation.”

Mrs. Crane nodded, and raised one thin eyebrow. “My, you look so young. It’s hard to believe you’re a doctor.” She giggled. “I’m sorry, that was rude of me.”

“Not at all.” Dr. Carlisle lifted one of Mrs. Crane’s delicate wrists and felt gently for a pulse. “I take it as a compliment.”

“It will be even more of a compliment when you’re my age. I just turned eighty-seven three weeks ago.”

“Well, happy belated birthday. I hear you had kind of a rough night last night.”

Mrs. Crane gave a little

tsk and a dismissive gesture of her hand. “Just a few palpitations, that’s all. Nothing this old heart of mine hasn’t seen a hundred times before.”

“Still, let’s give a listen.” Dr. Carlisle pressed his stethoscope to her chest. Other than a slight heart murmur, the beat sounded steady and strong—remarkable for someone her age.

“How long will Dr. Kelly be away?” Mrs. Crane asked, as Dr. Carlisle continued his examination.

“Two weeks. He and his family went to Hawaii.”

“Oh, Hawaii, how lovely. Such a nice man, and with a beautiful wife and two wonderful children. He’s shown me pictures.”

Dr. Carlisle nodded. “They’re nice folks.” He pointed to a small framed photograph of a somewhat younger Mrs. Crane with a tall, well-built man, who appeared to be about thirty. The man was darkly good looking, with a short, clipped beard and angular features. He wore a confident smile, and stood behind Mrs. Crane, who was seated, her legs primly crossed at the ankle. The man had his hand on her shoulder.

“Your son?” Dr. Carlisle asked.

Mrs. Crane nodded, and smiled fondly. “Yes, that’s Derek. My only son.”

“Do you get to see him often?”

“Oh, yes. He visits me every day, especially now that I’m here in the nursing home.” She paused and sighed. “His father was Satan, you know.”

Dr. Carlisle froze, and he just stared at her. She didn’t react, just maintained her gentle smile, her blue eyes regarding him with grandmotherly fondness.

He must have misheard her. What did she say?

His father was a saint. His father liked satin. His father was named Stan. His father looked like Santa. But each of those collided with his memory, which stubbornly clung to what it had first heard. Finally, he said, “I beg your pardon?”

“Satan,” Mrs. Crane said, her expression still mild and bland. “That’s Derek’s father. Lucifer. He used to visit, too, quite often, when Derek was little, but I expect he has other concerns these days.” She giggled again. “And I’m sure he’s had dalliances with other ladies since my time. Quite a charmer, you know, whatever else you might say about him.”

“Oh,” Dr. Carlisle croaked out. “That’s interesting.”

“Well, of course, you couldn’t ask him to be faithful.” If she heard his tentative tone, she gave no sign of it. “He isn’t that type. I did have to put up with a great deal of disapproval from people who thought it was immoral that I had a child out of wedlock. But after all—” she tittered—“what else could they have expected? He’s Satan, after all.”

Dr. Carlisle cleared his throat. “Yes, well, Mrs. Crane, I have to finish my examination of you, and see a couple of other patients this morning, so…” He trailed off.

Mrs. Crane gave her little wave of the hand again. “Oh, of course, doctor. I’m being a garrulous old woman, going on like that. I’m sorry I’ve kept you.”

“It’s no problem, really. And I wouldn’t worry about the palpitations—usually they’re not an indication of anything serious, especially if they don’t last long, as in your case. Your blood pressure is fine, and your last blood work was normal, so I don’t think you have anything to worry about.”

“I tried to tell the nurse that. But she insisted that I see the doctor this morning. I’m sorry I’m keeping you away from patients who need your help more than I do.”

“No worries, Mrs. Crane.” Dr. Carlisle hung his stethoscope around his neck. “Take care, and have a nice day.”

“You too, doctor. It’s been lovely talking to you.”

Dr. Carlisle opened the door, and exited into the hall, feeling a bit dazed.

He stood for a moment, frowning slightly, and then came to a decision. He walked off down the hall toward the nurses’ station, and set his clipboard on the counter, and leaned against it.

“Excuse me, nurse…?” He smiled. “I’m covering for Dr. Kelly this week and next. I’m Dr. Carlisle—my office is up at Colville General.”

The nurse, a slim, middle-aged woman with gold-rimmed glasses and short salt-and-pepper hair, gave him a hand. “I’m glad to meet you. Dana Treadwell. If there’s anything I can do…”

“Well, actually,” Dr. Carlisle said, “I do have a question. About Mrs. Crane, in 214.”

Dana gave him a quirky half-smile. “She’s an interesting case.”

Dr. Carlisle nodded. “That’s my impression. She’s here because of advanced osteoporosis, but is there anything else that you can tell me that might be helpful?”

“Has periodic mild cardiac arrhythmia. She had a full cardio workup about six months ago, showed nothing serious of note. Some tendency to elevated blood pressure, but nothing that medication can’t keep in check.” She paused, gave Dr. Carlisle a speculative look. “Some signs of mild dementia.”

“That’s what I wanted to ask you about. Is she… is she delusional?”

“That depends on what you mean,” Dana said. “Mentally, I hope I’m as with it when I’m eighty-seven. But she is prone to… flights of fancy. Particularly about her past.”

Dr. Carlisle didn’t answer for a moment. Should he mention the whole Satan thing? He decided against it. “She does seem to like telling stories,” he finally said.

Dana's smile turned into a full-fledged grin. “That she does.”

***

The following day, Dr. Carlisle was making his rounds, and passed Mrs. Crane’s room, and heard a male voice. Curiosity did battle with reluctance to talk to her again, and curiosity won. He knocked lightly, then stepped into the room.

Mrs. Crane looked up from a conversation she was having with a man who was seated at the edge of the bed, gently holding her hand. When the man turned toward him, Dr. Carlisle immediately recognized him as the man in the photograph—noticeably older, perhaps in his mid to late fifties, but clearly the same person. He still had the same carefully-maintained short beard, the same dark handsomeness, the same sense of strength, energy, presence.

“Oh, doctor, I’m so glad you’ve stopped by!” Mrs. Crane said. “This is my son, Derek.”

“Dorian Carlisle,” Dr. Carlisle said. “Nice to meet you. I’m going to be your mother’s doctor for the next two weeks, until Dr. Kelly returns.”

Derek got up and extended a hand. “Derek Crane." They clasped hands. Derek’s hand jerked, and a quick flinch crossed his face.

“Sorry,” Dr. Carlisle said, almost reflexively.

“It’s nothing. Three weeks ago, I hurt my hand doing some home renovations. I guess it’s still not completely healed.”

“I didn’t mean to…” Dr. Carlisle started, but Derek cut him off.

“It’s nothing. Mom has been telling me about your visit yesterday. It sounds like she talked your ear off.”

Dr. Carlisle smiled. “Not at all. It was a pleasure. I’d much rather chat with my patients and get to know them—otherwise, all too easily this job starts being about symptoms and treatments, and stops being about people.”

Mrs. Crane beamed at them. “Well, it’s so nice of you to take time from your busy schedule to stop in. I haven’t had any more palpitations.”

“That’s good,” Dr. Carlisle said. “I just wanted to see how you were doing. Nice to meet you, Derek.”

“Likewise.” Derek smiled.

Was there something—tense? speculative? about the smile?

No, that was ridiculous. Mrs. Crane had just primed him to be wary of her son because she’s delusional.

Dr. Carlisle exited the room, and then stopped suddenly, his face registering shock. He looked down at his hands. On his right ring finger he wore his high school class ring, from St. Thomas More Catholic Academy. He raised the ring to his eye, and saw, on each side of the blue stone in the setting, a tiny engraved cross.

***

That night, Dr. Carlisle told his girlfriend about Mrs. Crane over dinner.

“Now I want to meet this lady.” Nicole grinned.

“Can’t do that. I can’t even tell you her name. Privacy laws, and all that. I probably shouldn’t have even told you as much as I did.”

“It’s not like I’m going to go and tell anyone. And I want to hear about your job. It’s a huge part of your life.”

He took a sip of wine. “And this one was just so out of left field. I’ve dealt with people with dementia before, but they always show some kind of across-the-board disturbance in their behavior. This was like, one thing. In other respects, she seems so normal.”

“You didn’t talk to her that long.”

“No,” he admitted. “But you learn to recognize dementia when you see it. There was something about the way she looked at you—you could tell that her brain was just fine.”

Nicole raised an eyebrow. “So, you think she really did have a fling with Satan?”

He scowled. “No, of course not. But I think she believes it. But then…” he trailed off.

“But then what?”

“Her son jumped when I shook his hand, like he’d been shocked, or something. Then he made some excuse about how he’d hurt his hand a couple of weeks ago. But I noticed afterwards—I was wearing my high school ring. It’s got crosses engraved on it. And it was probably blessed by the bishop.”

“You’re kidding me, right? I thought you’d given up all of that religious stuff when you moved out of your parents’ house.”

“I did.”

“Maybe you didn’t,” Nicole said.

“All I’m saying is that it was weird.”

“You’re acting pretty weird, yourself.”

“I just wonder if it might not be possible to test it. See if maybe she’s telling the truth.”

“You do believe her! Dorian, you’re losing it. Satan? You think she got laid by Satan?”

He sat back in his chair. “I dunno,” he finally said. “All I can say is, she believes it enough that it made me wonder.”

***

The next day, other than a quick walk down the hall in the early morning hours, Dr. Carlisle avoided that wing of the nursing home until after lunch. When he finally went down the hallway toward room 214, he found that his heart was pounding. But he was stopped in the hall before he got to Mrs. Crane’s room by the nurse he’d spoken to two days earlier, Dana Treadwell.

“You missed some excitement,” Dana said.

“What happened?”

“A bad spill. Broken leg, possible fractured pelvis.”

Dr. Carlisle swallowed. “Which one of the patients?”

“Not a patient,” Dana said. “Mrs. Crane’s son. Slipped on wet tile right outside his mother’s room, and fell. Hard to believe you could be so badly hurt from a fall. They brought him to Colville General—I heard he’s still in surgery.”

“That’s too bad,” he said, trying to keep his voice level.

“Mrs. Crane was really upset.”

“I’m sure,” Dr. Carlisle said.

Dana seemed to pick up the odd tone in his voice. She raised one eyebrow. “Yeah. She was completely distraught.”

“Really?”

Dana nodded. “Especially after her ex-husband came by. We finally had to give her a sedative.”

Dr. Carlisle tried to think of something to say, and finally just choked out, “That’s too bad,” and turned away, hoping that Dana wouldn’t notice the ghastly expression on his face. He stuck his hand in his lab jacket pocket, and fingered the small glass bottle, now empty, that he’d filled early that morning at the font in the nursing home’s chapel.

“Oh, and Dr. Carlisle?” Dana said, and he turned.

“You might want to know that before we finally got her to go to sleep, your name came up.”

“Me?” Dr. Carlisle squeaked. “What did she say?”

“Something about your ‘needing an ocean of holy water.’ You might want to let Dr. Bennett handle her case from now on.” She smiled. “Just a suggestion.”

It's kind of sad that there are so many math-phobes in the world, because at its basis, there is something compelling and fascinating about the world of numbers. Humans have been driven to quantify things for millennia -- probably beginning with the understandable desire to count goods and belongings -- but it very quickly became a source of curiosity to find out why numbers work as they do.

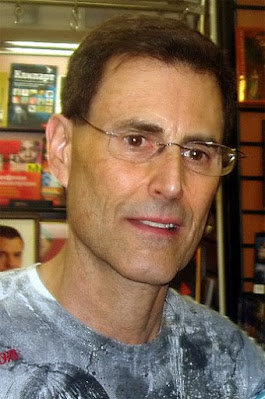

The history of mathematics and its impact on humanity is the subject of the brilliant book The Art of More: How Mathematics Created Civilization by Michael Brooks. In it he looks at how our ancestors' discovery of how to measure and enumerate the world grew into a field of study that unlocked hidden realms of science -- leading Galileo to comment, with some awe, that "Mathematics is the language with which God wrote the universe." Brooks's deft handling of this difficult and intimidating subject makes it uniquely accessible to the layperson -- so don't let your past experiences in math class dissuade you from reading this wonderful and eye-opening book.

[Note: if you purchase this book using the image/link below, part of the proceeds goes to support Skeptophilia!]