Earlier this month, I wrote a piece here at Skeptophilia on the reconstruction of an extinct language -- Timucuan, an indigenous language from northern Florida. As I pointed out in the earlier piece, these sorts of efforts aren't just entertaining linguistic puzzles. Each language encodes in its structure information about the culture, beliefs, and worldview of the people who spoke it, information which all too often is lost forever because of the effects of war, colonialism, and the simple but unfortunate effects of time on the written records.

As a linguist, I find this terribly sad. When a language goes extinct, it's as if an entire culture's collective memory is wiped clean. But astonishingly, sometimes artifacts will surface that allow us to reassemble an ancient language, bringing that long-extinguished knowledge back from the grave.

My eagle-eyed writer friend Gil Miller, always on the lookout for topics for Skeptophilia, sent me an article about such a miraculous resurrection this week. It has to do with the Amorite language, spoken by a people who lived in southern Mesopotamia on the order of four thousand years ago. While there's no doubt the people themselves were real enough -- they're mentioned in a number of records from the time, including the Bible -- the language is so poorly attested that some linguists questioned whether it even existed as a distinct language, suggesting that the Amorite people might have spoken a dialect of Akkadian.

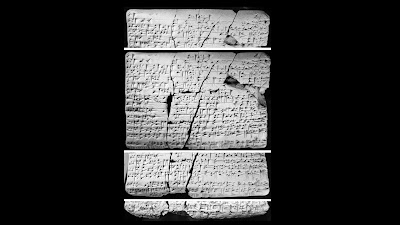

The discovery of a remarkable artifact in Iraq has put that to rest. It's a pair of clay tablets covered in cuneiform writing, describing everyday customs and religious practices in Akkadian, which is well understood by linguists -- with parallel text in Amorite.

The comparison to the Rosetta Stone is obvious. With the Rosetta Stone, however, the reason for having the inscription in three scripts (Greek, Egyptian hieroglyphic, and Demotic) was clear. It was an official decree from King Ptolemy V Epiphanes, so as an official document, it was important that it be readable to anyone in the region who was literate, regardless what script they knew. Here, though, the text is about such mundane matters that it's an open question why anyone wanted it written in two different languages. "The two tablets increase our knowledge of Amorite substantially, since they contain not only new words but also complete sentences, and so exhibit much new vocabulary and grammar," said Yoram Cohen, of Tel Aviv University, who co-authored the study. "The writing on the tablets may have been done by an Akkadian-speaking Babylonian scribe or scribal apprentice, as an impromptu exercise born of intellectual curiosity... Or it may be a sort of 'tourist guidebook' for Akkadian speakers who needed to learn Amorite."

Whatever its purpose, the tablets confirm that Amorite was a distinct language from the Western Semitic branch of the linguistic family tree (a branch it shares with Aramaic and modern Hebrew). More than just increasing our knowledge of a single long-dead language, however, it provides an impetus to keep looking for traces of ancient cultures. This amazing linguistic resurrection shows that lost doesn't necessarily mean forever -- and that with luck, perseverance, skill, and knowledge, we might still be able to gain a lens into what we thought was a long-gone culture.

****************************************

No comments:

Post a Comment