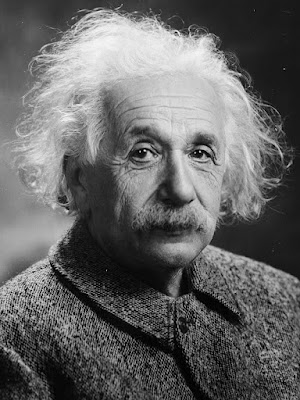

You know, I'm beginning to think that every time I want to write a piece about cosmology or physics, I should just write "Einstein wins again" and call it good.

One of my favorite science vloggers, theoretical physicist Sabine Hossenfelder, gives a wry nod to this every time Einstein's name comes up in her videos -- which is frequently -- giving a little sigh and a shake of the head, and saying "Yeah, that guy again."

You may recall that a couple of weeks ago I did a post about a possible paradigm shift in cosmology that could account for the mysterious "dark energy," a property of spacetime that is causing the apparent runaway expansion of the universe. While acknowledging that finding solid evidence for the contention is currently beyond our technical capabilities, I pointed out that it simultaneously does away with two of the most perplexing and persistent mysteries of physics -- dark energy, and the mismatch between the theoretical and experimentally-determined values of the cosmological constant. (Calling it a "mismatch" is as ridiculous an understatement as you could get; the difference is about 120 degrees of magnitude, meaning the two values are off by a factor of 1 followed by 120 zeroes).

But this week a new study out of the University of Sydney has shown that another of Einstein's relativistic predictions about an expanding universe has been experimentally verified, so maybe -- to paraphrase Mark Twain -- rumors of the death of dark energy were great exaggerations. A bizarre feature of the Theory of Relativity is time dilation, the fact that from the perspective of a stationary observer, the clock for a moving individual would appear to run more slowly. This gives rise to the counterintuitive twin paradox, which I first ran into on Carl Sagan's Cosmos when I was in college. If one of a pair of twins were to take off on a spaceship and travel for a year near the speed of light, then return to his starting point, he'd find that his twin would have aged greatly, while he only aged by a year. To the traveler, his clocks seemed to run normally; but his stay-at-home brother would have experienced time running much faster.

As an aside -- this is the idea behind my favorite song by Queen, the poignant and heartbreaking "'39," the lyrics for which were penned by the band's lead guitarist, astrophysicist Brian May. Give it a listen, and -- if you're like me -- have tissues handy.

In any case, the recent research looks at a weird feature of the effects of relativity on time. The prediction is that the expansion of the universe should affect all the dimensions of spacetime -- and therefore, in the early universe, time should (from our perspective) seem to have been running more slowly.

And that's exactly what they found. (Recall that when you're looking outward in space, you're looking backward in time.) The trick was finding a "standard clock" -- some phenomenon whose rate is steady, predictable, and well-understood. They used the fluctuations in emissions from quasars -- extremely distant, massive, and luminous proto-galaxies -- and found that, exactly as relativity predicts, the farther away they are (i.e. the further back in time you're looking), the more slowly these "standard clocks" are running. The most distant ones are experiencing a flow of time that (from our perspective) is five times slower than our clocks run now.

"[E]arlier studies led people to question whether quasars are truly cosmological objects, or even if the idea of expanding space is correct," said study co-author Geraint Lewis. "With these new data and analysis, however, we’ve been able to find the elusive tick of the quasars and they behave just as Einstein’s relativity predicts."The bizarre thing, though, is the "from our perspective" part; just like the traveling twin, anyone back then would have thought their clocks were running just fine. It's only when you compare different reference frames that things start getting odd. So it's not that "our clocks are right and theirs were slow;" both of us, from our own vantage points, think time is running as usual. Neither reference frame is right or wrong. The passage of time is relative to your velocity with respect to another frame.

Apparently it's also relative to what the fabric of spacetime around you is doing.

I'm not well-versed enough in the intricacies of physics to know if this really is a death blow to the paradigm-shifting proposal of a flat, static universe I wrote about a couple of weeks ago, but at least to my layperson's understanding, it sure seems like it would be problematic. So as far as the nature of dark energy and the problem of the cosmological constant mismatch, it's back to the drawing board.

Einstein wins again.

****************************************

No comments:

Post a Comment