When I had my DNA tested two years ago, I found out I have 330 distinctly Neanderthal markers in my genes. This, apparently, is well above average for people of western European descent, and may explain why I like to run around half-naked and prefer my steaks medium-rare.

In all seriousness, most people of European descent have Neanderthal ancestry; it's less common in people of African and Asian ancestry, and in the indigenous peoples of Australia and North America. It makes sense, once you know where they lived. The Neanderthals were a predominantly European species (or sub-species; the experts differ, and honestly, the definition of species is so mushy anyhow that it's probably splitting hairs to argue about it). They seem to have split off from the main population of hominins in the region something like five hundred thousand years ago. The first unambiguously Neanderthal bones are 430,000 years old, and they persisted until 40,000 years ago -- and we still don't know why they died out.

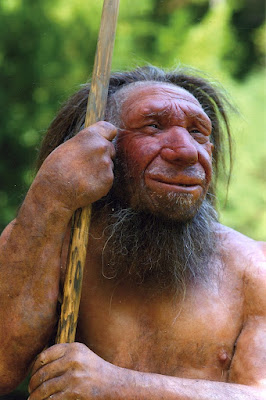

What's certain is that it wasn't a lack of sophistication and intelligence by comparison with contemporaneous Homo sapiens, whatever you might have gleaned from Jean Auel's The Clan of the Cave Bear. The Neanderthals were plenty smart. They had culture, made paintings on cave walls, and created jewelry. To judge by the Divje Babe flute they made music. They ceremonially anointed their dead, and appear to have had some concept of an afterlife. They had the same version of the FOX-P2 gene we do, suggesting they had spoken language. So despite my earlier quip, Neanderthals were far from the slow, sluggish, stupid "cave men" we often picture when we hear the name.

As my own ancestry indicates, there was a good bit of crossbreeding between Neanderthals and "modern" humans. (I put modern in quotes not only because it's self-congratulatory, but because all organisms on Earth have exactly the same time duration of their ancestral lineages; words like primitive and modern really "less changed since the common ancestor" and "more changed since the common ancestor," but those are clunky. So I'll continue to use primitive and modern, although with the caveat that they're not value judgments.)

What's interesting, though, is that the genetic input of the Neanderthals was asymmetrical. Of the Neanderthal markers we carry around, none are on the Y chromosome, indicating that something blocked any contribution of Y-chromosomal genes from our Neanderthal forebears. It's possible that the answer is simple -- that most inter-species matings were between "modern" human men and Neanderthal women. But now a new study from The American Journal of Human Genetics, by Fernando Mendez, G. David Poznik, and Carlos Bustamante (of Stanford University), and Sergi Castellano (of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology) has suggested another reason the Neanderthal Y chromosome didn't survive; mutations that caused male hybrid fetuses to spontaneously miscarry.

The authors write:

Sequencing the genomes of extinct hominids has reshaped our understanding of modern human origins. Here, we analyze ∼120 kb of exome-captured Y-chromosome DNA from a Neandertal individual from El Sidrón, Spain. We investigate its divergence from orthologous chimpanzee and modern human sequences and find strong support for a model that places the Neandertal lineage as an outgroup to modern human Y chromosomes—including A00, the highly divergent basal haplogroup. We estimate that the time to the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) of Neandertal and modern human Y chromosomes is ∼588 thousand years ago (kya)... This is ∼2.1 times longer than the TMRCA of A00 and other extant modern human Y-chromosome lineages. This estimate suggests that the Y-chromosome divergence mirrors the population divergence of Neandertals and modern human ancestors, and it refutes alternative scenarios of a relatively recent or super-archaic origin of Neandertal Y chromosomes. The fact that the Neandertal Y we describe has never been observed in modern humans suggests that the lineage is most likely extinct. We identify protein-coding differences between Neandertal and modern human Y chromosomes, including potentially damaging changes to PCDH11Y, TMSB4Y, USP9Y, and KDM5D. Three of these changes are missense mutations in genes that produce male-specific minor histocompatibility (H-Y) antigens. Antigens derived from KDM5D, for example, are thought to elicit a maternal immune response during gestation. It is possible that incompatibilities at one or more of these genes played a role in the reproductive isolation of the two groups.

Which is an interesting hypothesis. It's possible, of course, that there was more than one thing going on, here; there may also have been a skewed distribution of genders in inter-species matings as well as a higher death rate in male children of male Neanderthals and female "modern" humans. In fact, genetics and culture can sometimes create a feedback loop; the taboo in traditional Basque society against Basque women marrying non-Basque men is thought in part to have come from the high frequency amongst the Basques of the Rh negative blood group allele, resulting in children of Basque women (likely to be Rh negative) and non-Basque men (likely to be Rh positive) having a higher probability of dying of Rh incompatibility syndrome.

So sometimes cultural norms and genetics can intertwine in curious ways.

In any case, that's today's science story, tying together anthropology, genetics, and evolutionary biology, all particular fascinations of mine. And the fact that it could well be talking about some of my own ancestry adds a nice twist. Hopefully my forebears will forgive me for my jab about running around naked. Maybe the most Neanderthal thing about me is that I play the flute. Kind of turns the "cave man" trope upside down, doesn't it?

****************************************