Some days, optimism is just a losing proposition.

Today's reason for repeated facepalms has to do with COVID-19, better known as Wuhan coronavirus. It's not that the virus isn't scary enough by itself; there are currently

75,000 cases of confirmed COVID-19 worldwide, just over 2,000 of which have died of the illness. So the mortality rate still isn't as high as that of this year's influenza strains, but it's enough to be worrisome.

So I suppose it's an understandable enough impulse -- to ascribe some kind of underlying reason for an event that otherwise just appears to be an unfortunate example of the chaotic nature of the universe. But for fuck's sake, can't we try to restrain that a

little bit? Because the nonsense about this epidemic is really beginning to piss me off, and (I suspect) piss off the legitimate researchers, as well.

First, we have the evangelical wingnuts weighing in.

Rick Wiles, of

TruNews, who has been something of a frequent flier here at

Skeptophilia, jumped into the fray with

the statement that the coronavirus was God's "death angel" sent to visit destruction upon us because of the push in the United States for LGBTQ rights, and also for all the "filth" in television and movies. When the topic was raised of why (if that was so) the vast majority of cases were in China, Wiles didn't hesitate. It's because China has a "godless communist government that persecutes Christians." "God is about to purge a lot of the sin off this planet," he said.

Then there's the ever-entertaining Jim Bakker, who said that yes, coronavirus is bad, but

it can be "cured in twelve hours" by a solution of colloidal silver. That, coincidentally, he's selling by the bottle on his television show ("Call now to get yours! Only forty dollars!"). Never mind that colloidal silver doesn't do a damn thing for a viral infection, and also has a permanent side effect -- it turns your skin a bizarre blue/gray color, a condition called

argyria.

Maybe he's hoping that if all his followers turn blue, they won't feel so awkward supporting a politician who is orange. I dunno.

Then the conspiracy theorists got involved.

It couldn't possibly be that the COVID-19 was introduced into the human population in the usual fashion -- via accidental contact with an animal vector. This is virtually always the cause of so-called "emergent viruses," from the deadly Ebola, Marburg, and Lassa fevers to diseases like

chikungunya, which usually doesn't kill you but makes you wish it did (the name comes from the Makonde language of Tanzania, and means "doubled over with pain"). But no, that's too prosaic.

It has to be biowarfare.

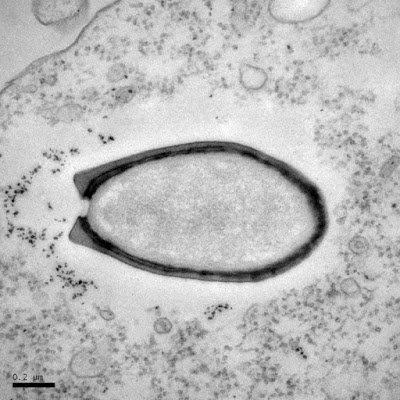

COVID-19 [Image is in the Public Domain, courtesy of the CDC]

The

first piece of the conspiracy theory came when Charles Lieber, chair of Harvard University's Department of Chemistry, was arrested and charged with "making a materially false statement" regarding funding received from China. So far, big news to academics, but not of much interest to the rest of us.

Until it came out that some of the funding came from Wuhan University.

Well, no way was

that a coincidence. Then a Chinese researcher was arrested trying to smuggle 21 vials of "biological substances," so of course there was no way it could be anything else but coronavirus, because Chinese + biological samples = deliberate viral terrorism.

Cue all the conspiracy fans to start having multiple orgasms.

Okay. Where to start?

First, Lieber's arrest had nothing to do with coronavirus, and neither did the arrest of Zaosong Zheng, the Chinese researcher/smuggler. And if you dig a little deeper, you find out that Zheng was trying to smuggle the samples

out of the United States and back to China, not the other way around (which is what you'd expect if there was some kind of horrible plot by the Chinese to cause a pandemic using a manufactured bioweapon), and... most importantly... the "biological substances" weren't even virus cultures. They were cancer cells that he was hoping to get back home so he could publish the data from the cultures under his own name and scoop the American researchers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, where he'd stolen them from.

But even that information didn't make much of a dent. So

The Lancet decided to respond. One of the most prestigious and respected medical journals in the world,

The Lancet published a couple of days ago

a statement by 27 medical researchers, epidemiologists, and health professionals saying that there was nothing artificial about COVID-19. They write:

The rapid, open, and transparent sharing of data on this outbreak is now being threatened by rumours and misinformation around its origins. We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin. Scientists from multiple countries have published and analysed genomes of the causative agent, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and they overwhelmingly conclude that this coronavirus originated in wildlife, as have so many other emerging pathogens. This is further supported by a letter from the presidents of the US National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine and by the scientific communities they represent. Conspiracy theories do nothing but create fear, rumours, and prejudice that jeopardise our global collaboration in the fight against this virus. We support the call from the Director-General of WHO to promote scientific evidence and unity over misinformation and conjecture.

There you have it. The people who have actually studied this stuff have spoken authoritatively. So when this came out, you would expect that the conspiracy theorists would chuckle in an embarrassed sort of way and say, "Wow, what a bunch of goobers we are."

You would be wrong.

This just reinforced their conviction that something big was afoot, because now they had proof that not only was COVID-19 a Chinese-manufactured bioweapon,

the evil scientists responsible were covering it up. How did they know this?

Because there was no evidence. Duh. You think evil super-conspirators are dumb enough to leave

evidence?

And because the whole story wouldn't be complete without an American politician getting involved, just a couple of days ago Tom Cotton, Senator from Arkansas -- who is in some kind of contest with Matt Gaetz and Louie Gohmert to see who has the lowest IQ in Congress --

stated that "we have to keep our minds open:"

I'm suggesting we need to be open to all possibilities and we need to demand that China open up and be transparent so a team of international experts can figure out exactly where this virus originated. We know it didn't originate in the Wuhan food market based on the study of Chinese scientists ... I'm not saying where it started, I don't know. We don't know because the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) won't open up to international experts. That's what we need to do so they can get to the bottom of where the virus originated and hopefully can effect a diagnostic test and vaccine for it.

Let's take the professor [Professor Richard Ebright of Rutgers University] He was ...in fact today cited in the Asia Times saying that it was quite possible that it was a laboratory incident. That's not saying this is a bioweapon, but we do know they were investigating and researching coronavirus in that laboratory. It could've been an accidental breach, it could've been a worker that was infected. My point is that we don’t know until we get all the evidence from the Chinese Communist Party, it is only responsible, not irresponsible, to keep an open mind about the hypotheses.

Okay. First of all, we

already have fucking international experts. 27 of them, in fact, who have stated unequivocally that COVID-19 is of natural origin. Second, if you actually

read the

Asia Times article (or in Cotton's case, have a staffer read it to him), you find out that Ebright said "there was no indication that the virus had been artificially modified," but "there was no way to rule out" that the epidemic hadn't started in a lab accident.

Which is an example of typical scientific caution. You can't rule something out for certain unless you have proof. No proof = there's still a possibility. But this is a far cry from Cotton's statement that "it's quite possible that it was a laboratory incident."

The whole thing is making me grind my teeth down to nubs.

But that's the problem with conspiracy theories. The more you argue, the more convinced the conspiracy theorists become. And if you're arguing, you're either a dupe or a shill. It's kind of the opposite of the scientific method; with conspiracy theories, the

less evidence you have, the more likely it is.

Because those conspirators are

just that sly.

Anyhow, that's the latest on coronavirus. It's bad, but not as bad as the flu, which we deal with every single year without people having complete meltdowns. It'll probably dwindle, the way most epidemics do -- no one I've talked to who knows about viruses and epidemiology is particularly concerned that this is going to be the next Black Death.

But try to convince the evangelical lunatics, conspiracy theorists, and Tom Cotton of that.

*******************************

This week's book recommendation is a fascinating journey into a topic we've visited often here at

Skeptophilia -- the question of how science advances.

In

The Second Kind of Impossible, Princeton University physicist Paul Steinhardt describes his thirty-year-long quest to prove the existence of a radically new form of matter, something he terms

quasicrystals, materials that are ordered but non-periodic. Faced for years with scoffing from other scientists, who pronounced the whole concept impossible, Steinhardt persisted, ultimately demonstrating that an aluminum-manganese alloy he and fellow physicists Luca Bindi created had all the characteristics of a quasicrystal -- a discovery that earned them the 2018 Aspen Institute Prize for Collaboration and Scientific Research.

Steinhardt's book, however, doesn't bog down in technical details. It reads like a detective story -- a scientist's search for evidence to support his explanation for a piece of how the world works. It's a fascinating tale of persistence, creativity, and ingenuity -- one that ultimately led to a reshaping of our understanding of matter itself.

[Note: if you purchase this book from the image/link below, part of the proceeds goes to support

Skeptophilia!]