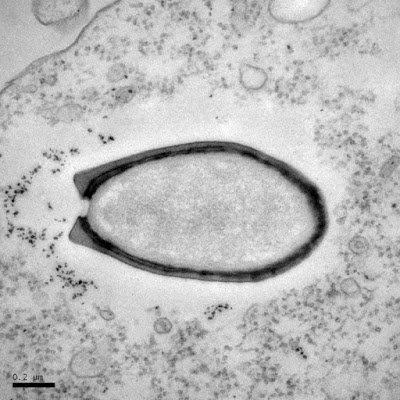

An announcement a few weeks ago by microbiologist Jean-Michel Claverie of Aix-Marseille University that he and his team had successfully resuscitated a 48,500-year-old virus from the Siberian permafrost brought horrified comments like, "I read this book, and it didn't end well" and "wasn't this an episode of The X Files? And didn't just about everyone die?" It didn't help when Claverie's team mentioned that the particular virus they brought back to life belonged to a group called (I shit you not) "pandoraviruses," and the media started referring to them by the nickname "zombie viruses."

The team hastened to reassure everyone that the virus they found is a parasite on amoebas, and poses no threat to humans. This did little to calm everyone down, because (1) not that many laypeople understand viral host specificity, and (2) shows like The Last of Us, in which a parasitic fungus in insects jumps to human hosts and pretty much wipes out humanity, have a fuckload more resonance in people's minds than some dry scientific paper.

What's scary about Claverie's study, though, isn't what you might think. First, the good news. Not only is the virus they found harmless to humans, the team is made up of trained microbiologists who are working under highly controlled sterile conditions. Despite what the "lab leak" proponents of the origins of COVID-19 would have you believe, the likelihood of an accidental release of a pathogen from a lab is extremely unlikely. (The overwhelming consensus of scientists is that COVID is zoonotic in origin, and didn't come from a lab leak, accidental or deliberate.) So the obvious "oh my god what are we doing?" reaction, stemming from a sense that we shouldn't "wake up" a frozen virus because it could get out and wreak havoc, is pretty well unfounded.

What worries me is the reason Claverie and his team are doing the research in the first place.

Permafrost covers almost a quarter of the land mass of the Northern Hemisphere. A 2021 study found that every gram of Arctic permafrost soil contains between a hundred and a thousand different kinds of microbes, some of which -- like Claverie's pandoravirus -- have been frozen for millennia. A three-degree Celsius increase in global average temperature could melt over thirty percent of the upper layers of Arctic soil.

So potentially, what Claverie's team did under controlled, isolated conditions could happen out in the open with nothing to keep it in check.

Concern over this isn't just hype. In 2016, melting permafrost in Siberia thawed out the carcass of a reindeer that had died of anthrax. Once thawed, the spores were still viable, and by the time the incident had been contained, dozens of people had been hospitalized, one had died, and over two thousand reindeer had been infected. Anthrax isn't some prehistoric microbe that scientists know nothing about, which actually acted in our favor; once it was identified, doctors knew how to treat it and prevent its further spread.

But what if the thawing frost released something we haven't had exposure to for tens of thousands of years, and that was unknown to science?

"We really don’t know what’s buried up there," said Birgitta Evengård, a microbiologist at Umeå University in Sweden, which in a few words says something that is absolutely terrifying.****************************************

No comments:

Post a Comment