When you think about it, writing is pretty weird.

Honestly, language in general is odd enough. Unlike (as far as we know for sure) any other species, we engage in arbitrary symbolic communication -- using sounds to represent words. The arbitrary part means that which sounds represent what concepts is not because of any logical link; there's nothing any more doggy about the English word dog than there is about the French word chien or the German word Hund (or any of the other thousands of words for dog in various human languages). With the exception of the few words that are onomatopoeic -- like bang, bonk, crash, and so on -- the word-to-concept link is random.

Written language adds a whole extra layer of randomness to it, because (again, with the exception of the handful of languages with truly pictographic scripts), the connection between the concept, the spoken word, and the written word are all arbitrary. (I discussed the different kinds of scripts out there in more detail in a post a year ago, if you're curious.)

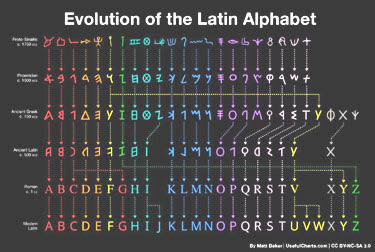

Which makes me wonder how such a complex and abstract notion ever caught on. We have at least a fairly good model of how the alphabet used for the English language evolved, starting out as a pictographic script and becoming less concept-based and more sound-based as time went on:

The reason all this comes up is that a recent paper in the Cambridge Archaeology Journal is claiming that marks associated with cave paintings in France and Spain that were long thought to be random are actual meaningful -- an assertion that would push back the earliest known writing another fourteen thousand years.

The authors assessed 862 strings of symbols dating back to the Upper Paleolithic in Europe -- most commonly dots, slashes, and symbols like a letter Y -- and came to the conclusion that they were not random, but were true written language, for the purpose of keeping track of the mating and birthing cycles of the prey animals depicted in the paintings.

The authors write;

[Here we] suggest how three of the most frequently occurring signs—the line <|>, the dot <•>, and the <Y>—functioned as units of communication. We demonstrate that when found in close association with images of animals the line <|> and dot <•> constitute numbers denoting months, and form constituent parts of a local phenological/meteorological calendar beginning in spring and recording time from this point in lunar months. We also demonstrate that the <Y> sign, one of the most frequently occurring signs in Palaeolithic non-figurative art, has the meaning <To Give Birth>. The position of the <Y> within a sequence of marks denotes month of parturition, an ordinal representation of number in contrast to the cardinal representation used in tallies. Our data indicate that the purpose of this system of associating animals with calendar information was to record and convey seasonal behavioural information about specific prey taxa in the geographical regions of concern. We suggest a specific way in which the pairing of numbers with animal subjects constituted a complete unit of meaning—a notational system combined with its subject—that provides us with a specific insight into what one set of notational marks means. It gives us our first specific reading of European Upper Palaeolithic communication, the first known writing in the history of Homo sapiens.The claim is controversial, of course, and is sure to be challenged; moving the date of the earliest writing from six thousand to twenty thousand years ago isn't a small shift in our model. But if it bears up, it's pretty extraordinary. It further gives lie to our concept of Paleolithic humans as brutal, stupid "cave men," incapable of any kind of mental sophistication. As I hope I made clear in my first paragraphs, any kind of written language requires subtlety and complexity of thought. If the beauty of the cave paintings in places like Lascaux doesn't convince you of the intelligence and creativity of our distant forebears, surely this will.

So what I'm doing now -- speaking to my fellow humans via strings of visual symbols -- may have a much longer history than we ever thought. It's awe-inspiring that we landed on this unique way to communicate; even more that we stumbled upon it so long ago.

****************************************

No comments:

Post a Comment