In the episode of The X Files called "Ice," Fox Mulder and Dana Scully are sent with a small team of scientists to a remote Arctic research station in order to investigate the murder-suicide of its entire crew. When they get there, they find one survivor -- the station's mascot, a dog, who shows signs of hyperaggressive behavior (obviously) reminiscent of what afflicted the researchers.

They eventually figure out what happened, but not before two of the people accompanying them are dead, and both Mulder and the third scientist are obviously afflicted with the same malady. In digging up and thawing out permafrost, the researchers had inadvertently reanimated a deep-frozen parasitic nematode that causes drastic behavioral changes, and is transmissible from bites. They do find a way to get rid of the infection, saving the lives of Mulder, the infected scientist, and (thank heaven) the dog, but the U.S. government destroys the base before any further study of the worm or its origins can be made.

It's a highly effective and extremely creepy episode, doing what The X Files did best -- leaving you at the end with the feeling of, "This ain't actually over."

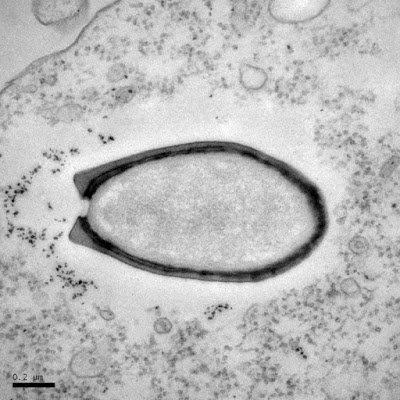

I was forced unwillingly to recall my watching of "Ice" by two news stories this week. In the first, scientists have "reawakened" -- deliberately this time -- a nematode that has been frozen for 46,000 years in the Siberian permafrost.

Dubbed Panagrolaimus kolymaensis, it's a previously unknown species. This doesn't mean it's a truly prehistoric species; Phylum Nematoda is estimated to contain about a million species, of which only thirty thousand have been studied, classified, and named. So it could well be that Panagrolaimus exists out there somewhere, in active (i.e. unfrozen) ecosystems, and the invertebrate zoologists just hadn't found it yet.

Still, it's hard not to make the alarming comparison to the horrific events in "Ice" (and countless other examples of the "reanimating creatures frozen in the ice" trope in science fiction). This reaction is somewhat ameliorated by the fact that two-thirds of the nematode species known are harmless to humans, and even the ones that are parasitic usually aren't life-threatening. There are a few truly awful ones -- which, for the sakes of the more sensitive members of my audience, I'll refrain from giving details about -- but most nematodes are harmless, so chances are Panagrolaimus is as well.

On the other hand, it doesn't mean that thawing frozen stuff out is risk-free, and the problem is, because of climate change, thawing is happening all over the world even without reckless scientists being involved. The second study, conducted at the European Commission Joint Research Centre, appeared in a paper in PLOS - Computational Biology and described a digital simulation of a partially frozen ecosystem (that contained living microbes in suspended animation). They looked at how the existing community would be affected by the introduction of the now reawakened species -- and the results were a little alarming.

It has been tempting to think that because the entire ecosystem has changed since the microbes were frozen, if they were reanimated, there'd be no way they could compete with modern species which had evolved to live in those conditions. In other words, the thawed species would be unable to cope with the new situation and would probably die out rapidly. In fact, that did happen to some of them -- but in these models, the ancient microbes often survived, and three percent of them became dominant members of the ecosystem.

One percent actually outcompeted and wiped out modern species.

"Given the sheer abundance of ancient microorganisms regularly released into modern communities," the authors write, "such a low probability of outbreak events still presents substantial risks. Our findings therefore suggest that unpredictable threats so far confined to science fiction and conjecture could in fact be powerful drivers of ecological change."Now, keep in mind that this was only a simulation; no actual microbes have been resuscitated and released into the environment.

Yet.

Anyhow, there you have it. Something new from the "Like We Didn't Already Have Enough To Worry About" department. Maybe I shouldn't watch The X Files. How about Doctor Who? Let's see... how about the episode "Orphan 55"? *reads episode summary* "...about a future Earth so devastated by climate change that the remnants of humanity have actually evolved to metabolize carbon dioxide instead of oxygen..."

Or maybe I should just shut off the television and hide under my blankie for the rest of the day.

****************************************