The southern tip of mainland Italy is called Calabria. It's a strikingly beautiful place, containing three national parks (Pollino National Park, Sila National Park and Aspromonte National Park), and a stretch of coastline -- near Reggio, facing across the Straits of Messina to Sicily -- that poet Gabriele D'Annunzio called "the most beautiful kilometer in Italy." It's a region blessed with more than its share of dramatic scenery.

Calabria forms the "toe of Italy's boot." I remember noticing the country's odd shape when I was a kid and first became fascinated with maps (a fascination that remains with me today), and wondering why it looked like that; back then, when plate tectonics was still a new science, I doubt they really understood it on a level any deeper than "it's near a plate margin, and that moves stuff around." Today, we have a much more detailed understanding of the geology of the area, and it is complex.

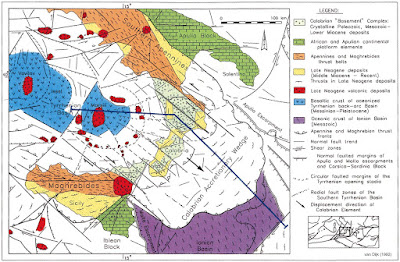

On its simplest level, the entire southern half of Italy is being pushed to the southeast, and it's riding up and over the northern edge of the African Plate. This process is responsible not only for the volcanism of the region -- Mount Etna being the most obvious example -- but the massive earthquakes that have shaped it, in part creating the gorgeous topography. (It also has made it a dangerous place to live. The Messina Earthquake of 1908, with an epicenter right across the straits from Calabria, had a magnitude of 7.1 and killed an estimated eighty thousand people, most of them in the first three minutes after the quake struck and the majority of the buildings collapsed.)

As interesting as the geology of the region is, that's not what spurred me to write about the topic today. What I'd like to tell you about is Calabria's tremendous linguistic diversity, an embarrassment of riches packed into a small geographical area. The main language, of course, is standard Italian, but a great many people there (especially in the southern parts) speak Calabrian, a Greek-influenced-Latin derivative that is mostly mutually intelligible with Italian but has some distinct vocabulary and pronunciations.

Then there's Grecanico, which is derived from an archaic dialect of Byzantine Greek, and is spoken by a group of people descended from folks who settled in the region more than a thousand years ago and have somehow maintained their ethnic identity the whole time. It's written with the Latin, not Greek, alphabet -- but other than that has more in common with Thessalian Greek than with Italian.

Another language that has little to do with Italian is Arbëresh, a dialect of Albanian brought in with migrants during the Late Middle Ages. From some of its idiosyncrasies, it appears to be related to Tosk Albanian, a group of dialects spoken in the southern parts of Albania, near the border of Greece. It's astonishing that we can still identify the part of the world the ancestors of the Arbëreshë people came from centuries ago -- by the peculiarities of the language they have spoken during the more than six hundred years they've lived in isolated communities in Calabria.

Finally, there's Gardiol, which is related to Occitan (also known as Provençal or Languedoc), the Romance language widely spoken in the southern half of France. Like with Calabrian (and also Catalan in Spain), most Occitan speakers in France speak the majority language as well, but use Occitan when speaking with family, friends, and locals. The ancestors of the speakers of Gardiol came in with the persecution of the Waldensian "heretics" in France in the thirteenth century, who found a refuge in a thinly-populated part of northern Calabria. Once again -- amazingly -- they've retained their ethnic identity and language through all the vagaries of time since their arrival.

All of that -- and standard Italian as well -- in an area of around fifteen thousand square kilometers, a little more than the size of the state of Connecticut.

UNESCO describes all four of these languages -- Calabrian, Grecanico, Arbëresh, and Gardiol -- as "in serious danger of disappearing." It's sad to think of these footprints of history vanishing, and taking along with them pieces of human culture that somehow had persisted for centuries. I understand why this happens; in modern life, speaking and writing the dominant language is not only useful, it's often essential for getting a job and making a living. These little pockets of other languages survived better when people had little mobility and even less connectedness to others living far away. In today's world, they seem doomed.

Change is the fate of all things, but it inevitably comes with a sense of loss. The linguistic diversity of the beautiful region of Calabria will, very likely, soon be gone. Like biodiversity loss, this diminishes the richness of our world. I hope that linguists are working to catalog and study these unique languages -- before the last native speakers are gone forever.