Here's a question I wonder if you've ever pondered:

Why do the Spanish and French speak Romance languages and not Germanic ones?

It's not as weird a consideration as it might appear at first. By the time the Western Roman Empire collapsed in the last part of the fifth century C.E., the entire western part of Europe had been completely overrun by Germanic tribes -- the Franks, the Burgundians, and especially the Visigoths. This latter group ended up controlling pretty much all of southern France and nearly the entirety of Spain, and their king, Euric, ruled the whole territory from his capital at Toulouse. It was Euric who deposed the last Western Roman emperor, poor little Romulus Augustulus, in 476 -- but showing unusual mercy, sent him off to a (very) early retirement at a villa in Campania, where he spent the rest of his life. That he felt no need to execute the kid is a good indicator of how solidly Euric and the Visigoths were in control.

So the Germanic-speaking Goths more or less took over, and not long after that the (also Germanic) Franks and Burgundians came into northern France and established their own territories there. The country of France is even named after the Franks; but their language, Franconian, never really took hold inside its borders.

Contrast this to what happened in England. The Celtic natives, who spoke a variety of Brythonic dialects related to Welsh and Cornish, were invaded during the reign of the Emperor Claudius in the year 43 C.E., and eventually Rome controlled Britain north to Hadrian's Wall. But when all hell broke loose in the fifth century, and the Roman legions said, "Sorry, y'all'll have to deal with these Saxons on your own" and hauled ass back home, the invaders' Germanic language became the lingua franca (pun intended) of the southern half of the island, with the exception of the aforementioned Welsh and Cornish holdouts.

All three places had been Roman colonies. So why did France and Spain end up speaking Romance languages, and England a Germanic one?

The easier question is the last bit. Britain never was as thoroughly Romanized as the rest of western Europe; it always was kind of a wild-west frontier outpost, and a great many of the Celtic tribes the Romans tried to pacify rebelled again and again. When the Romans troops withdrew, there weren't a lot of speakers of Latin left -- exceptions were monasteries and churches. Most of the locals had retained their original languages, and when the British Celts told the troops "Romani ite domum" (more or less), they just picked up where they'd left off.

The situation was different in France and Spain. By the fifth century, those had both been solidly Roman for three hundred years. The Celtic/Gaulish natives were by this time thoroughly subjugated, and many had even thrown their lot in with the conquerors, rising to become important figures. (One example is first century B.C.E. writer and polymath Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus, who despite his Roman name was from the Celtic Vocontii tribe in the western foothills of the Alps.) Business, record-keeping, and administration were all conducted in Latin; most of the cities were predominantly Latin-speaking.

The Germanic tribes who swept through western Europe in the fourth and fifth centuries had an interesting attitude. They didn't want to destroy everything the Romans had built; they just wanted to control it, and have access to all the wealth and land. They didn't even care if the Roman town-dwellers stayed put, as long as they acknowledged the Goths' overlordship. (Which almost all of them did, given that there were no other options. Practical folks, the Romans.)

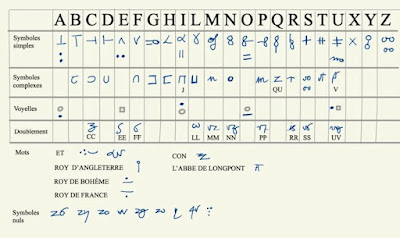

The invading Visigoths, Franks, and Burgundians had no written language we know of, so when they settled in to rule the place -- and most importantly, to do business with the local landowners -- their only real option was to learn Latin. Latin became the prestige language, the language you learned if you wanted to go places, much the way English is now in many parts of the world.

The result was that Latin-derived Old French and Old Spanish were eventually adopted by the Germanic-descended ruling class, ultimately being spoken throughout the region, while the opposite pattern had happened across the Channel in England. Interesting that the Franks gave their name to the country of France and its language, but the only modern language descended from Franconian is one spoken two countries northeast of there -- Dutch.

It's always fascinating to me to see how chance events alter the course of history. You can easily see how it could have gone the other way -- the Visigoths might have been more determined to eradicate every trace of Romanness, the way so many conquerors have done. Instead, they saw the value in leaving it substantially intact. Not because they had such deep respect for other cultures -- they weren't so forward thinking as all that -- but because they recognized that they could use the Roman knowledge, language, and infrastructure for their own gain. The result is that my Celto-Germanic ancestors spoke a language derived from Latin, even though by that time it was about the only Roman thing about them.

****************************************

|

_3.jpg)