This is a piece I wrote a few years ago, based on something that happened to a friend of mine (and scared the absolute bejeezus out of her). It's more a short vignette than a story, but hopefully it'll give you a nice shudder up your spine.

***********************************

Cat's Eyes

Cori turned the corner onto Waltham Street and stopped for a moment, looking up the steep hill to where there was a sprinkling of lights—the college, her dorm, and bed. It had been a long, exhausting, but exhilarating evening. Dinner with five friends at Borley’s, which had the best burgers in Colville, and then an evening spent swing dancing. The dance didn’t end until midnight, and when the doors of the Colville Community Center opened to spill out light and laughing, talking people into the night, Cori said her goodbyes and declined offers of a ride. She was hot and sweaty and the night air was cool and inviting, and she’d always liked walking.

She followed Waltham for three blocks, and then turned onto Marsh Street. Marsh skirted Catanic Creek, tumbling and bubbling downhill in its rocky course, but her feet carried her the opposite way, up a punishingly steep hill lined with old shop fronts.

She stopped for a moment in front of Ballechin’s Used Books. Its windows were dark, but she pressed her nose against the glass. Old books were a passion, and her choice of English Literature as a major was in part driven by a yearning to be surrounded by them. Leather bindings held magic. The crackling, yellowed pages spoke to her of years past and people long dead; and that dusty, old-book smell wasn’t quite like any other smell in the world. This bookstore had tens of thousands of titles, and in the light from the streetlight, Cori could just barely make out the metal shelves receding backwards into the shadowy interior.

She turned away with a sigh. A trip to Ballechin’s would have to wait until she had more money, and also, of course, until it was open.

She had walked another block when she saw, in the harsh yellow glare, a figure approaching her, coming down Marsh Street on the same side of the road. Cori was a confident walker, but like most women, she was never free from the lurking worry of being the victim of violence. Her heart gave a quick gallop, but then she saw with relief that the person approaching her wasn’t male. One thing checked off the fear inventory. She seemed smaller than Cori was—a second thing checked off. Last, she was walking with the hesitant, shuffling gait of the elderly—fear inventory completed, signed, and filed away. Cori shivered as the last of the panic left her body.

As the woman approached, she saw that she was dressed in a dark, full-length coat, and was wearing a scarf tied over her head. This seemed odd, for a mild night in September, but older people frequently felt the cold more keenly than the young, and as the distance between them shortened, Cori smiled at the memory of her own grandmother, who surreptitiously turned up the thermostat whenever she came to visit and she thought no one was looking.

Thirty feet, twenty, ten. The woman’s face was in deep shadow, but Cori saw she was smaller even than she’d thought at first, barely five feet tall, and hunched over. Cori felt a sudden desire to see the woman’s face.

Why? She was probably just some poor old crazy cat woman, out walking to the 7-Eleven to get some canned food for her twenty-eight cats. The image, which she had thought at first was funny, suddenly struck her as terrifying, and she realized suddenly that she

didn't want to see her face. She didn't want to see it at all…

They passed close, almost brushing elbows. Cori would have had to step into the street to be any farther away from her. And as they passed, the woman looked up at Cori, and Cori found that she had to turn toward her. Her head moved as if it were being pulled by a string. Unwillingly, Cori looked down at the woman, and for a moment, their eyes met.

The woman had cat’s eyes.

Her lined face was heavily made up, and around her eyes was eye shadow and liner, drawing the shape of her eyes into an almond, feline slant. The irises were dark, so dark that they looked all pupil. She looked straight into Cori’s eyes, unblinking, and with an expression of such malignity that it was almost non-human.

Cori gasped, and with an effort continued her forward motion, taking another stumbling step and nearly colliding with the lamp post. The gaze broke, and Cori’s head snapped around forward. She continued her walk uphill with a jittering, uneven gait, her heart hammering in her chest.

That woman just stole my soul.The thought came to her so suddenly that it seemed to come from outside her, in a voice not hers. Her breath was coming in whistly gasps, and she kept herself from looking back only by main force of will.

She wouldn't follow her. Cori knew that for certain. The woman had what she wanted. She'd got Cori's soul, and now she was taking it away.

The old woman had no use for her body.

She couldn’t help herself. She slowed her step, turned to look. Part of her felt terrified that she’d turn, and the old woman would be right there behind her, staring up at her with those baleful cat’s eyes.

But she wasn’t. She had evidently continued her walk downhill, and her stooped back, swathed in its dark coat, was all she could see in the distance.

Cori’s foot struck a steel grate in the sidewalk with a loud thunk.

And the old woman stopped, then slowly turned. From fifty feet away, Cori could feel the intensity of those eyes, staring right at her. That was when Cori’s nerve broke, and she began to run uphill, her breath coming in tight, desperate whimpers. She only halted when there was a stitch in her side so painful that she couldn’t continue.

She fell, gasping, against the front wall of another old, dilapidated store, and for a few minutes she stood there, breathing hard, trying to massage her side to get the spasm to loosen up. She turned and looked through the window of the store front, and saw, sitting in the window, the face of a porcelain doll. She’d noticed this store before—it sold antique dolls to collectors. The doll in the window was dressed in vintage clothes, and had dark, curly hair. Its expressionless face stared at Cori blankly.

Cori lifted her eyes, and caught sight of her own reflection in the window, lit by the glare from the street lights.

She was a doll. A lifelike, beautiful doll, wavy blond hair in a stylish cut around her face, her skin perfect and blemish-free, every feature carved so as to be indistinguishable from the real thing. She raised a hand to her face, touched her cheek, watched her mouth pull back into a horrified grimace, and then looked into her own eyes.

Her own blank, empty eyes.

She turned away from the window, and looked down the hill toward the corner of Marsh and Waltham, but the woman had already vanished from sight.

*********************************

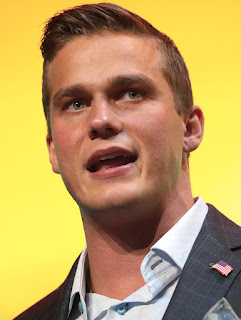

This week's Skeptophilia book-of-the-week combines cutting-edge astrophysics and cosmology with razor-sharp social commentary, challenging our knowledge of science and the edifice of scientific research itself: Chanda Prescod-Weinsten's The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred.

Prescod-Weinsten is a groundbreaker; she's a theoretical cosmologist, and the first Black woman to achieve a tenure-track position in the field (at the University of New Hampshire). Her book -- indeed, her whole career -- is born from a deep love of the mysteries of the night sky, but along the way she has had to get past roadblocks that were set in front of her based only on her gender and race. The Disordered Cosmos is both a tribute to the science she loves and a challenge to the establishment to do better -- to face head on the centuries-long horrible waste of talent and energy of anyone not a straight White male.

It's a powerful book, and should be on the to-read list for anyone interested in astronomy or the human side of science, or (hopefully) both. And watch for Prescod-Weinsten's name in the science news. Her powerful voice is one we'll be hearing a lot more from.

[Note: if you purchase this book using the image/link below, part of the proceeds goes to support Skeptophilia!]