Albert Einstein said it best: "Joy in looking and comprehending is nature’s most beautiful gift." Being able to look around you and think, "Okay, now I understand a little bit more of the universe" is nothing short of a thrill.

I recall having that feeling when I first learned about the Cambrian Explosion, a sudden increase in biodiversity that occurred about 540 million years ago, and which produced virtually all the animal phyla we currently have today. I think it struck me that way because it was so contrary to the picture I'd had, of evolution slowly plodding along, from something like a jellyfish to something like a worm to something like a fish, through amphibians and reptiles and mammals, finally leading to us as (of course) the Pinnacle of Creation. That view, it seems, is substantially wrong. While there has been great change on many branches of the family tree of life, all of the basic branches diverged right about the same time.

Fascinating, too, that there were also a variety of branches that left no living descendants, that are so bizarre to our eyes that they look more like something from a science fiction movie. There's Dickinsonia:

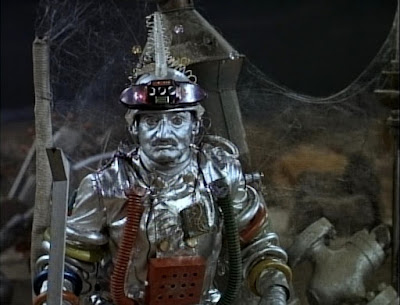

... and Anomalocaris, shown here as a model of what it might have looked like when alive:

... and the aptly named Hallucigenia, which could be straight out of a fever-dream:

... and my personal favorite, five-eyed, vacuum-cleaner-hose-equipped Opabinia:

If you'd like to find out more, I encourage you to read Stephen Jay Gould's awesome book Wonderful Life, which will tell you about these four creatures and a great many more besides.

The reason I bring this up is that some research out of Oxford University has elucidated not only the structure of these odd creatures, but the environment in which they lived. Having fossils from 540 million years ago that were sufficiently intact to determine what they'd looked like while alive is amazing enough; but being able to determine anything about the conditions under which they lived is downright astonishing. But that's just what Ross Anderson and Nicholas Tosca, of the Department of Sedimentary Geology at Oxford, and their team have done.

Their paper, which appeared in the journal Geology, described microscopic mineralogical analysis of the Burgess Shale of Canada and the Ediacaran Assemblage of Australia, two of the finest deposits of Cambrian Explosion fossils in the world. And what the geologists found allowed them to make a guess at where the likes of Opabinia and the rest lived: warm, shallow ocean ecosystems that had water rich in iron.

The iron content allowed the formation of the mineral berthierine, which is not only distinctive in its origins, but has an anti-bacterial effect that halted decomposition and prevented decomposition. This resulted in the phenomenally well-preserved fossils both sites are known for.

"Berthierine is an interesting mineral because it forms in tropical settings when the sediments contain elevated concentrations of iron," Anderson said. "This means that Burgess Shale-type fossils are likely confined to rocks which were formed at tropical latitudes and which come from locations or time periods that have enhanced iron. This observation is exciting because it means for the first time we can more accurately interpret the geographic and temporal distribution of these iconic fossils, crucial if we want to understand their biology and ecology."

The whole thing is tremendously exciting. To not only have an idea of the appearance of these animals, but to be able to picture them in something like their actual habitat, gives us a glimpse of a world five times older than it was during the heyday of the dinosaurs. It's breathtaking to think about.

I'll end with a quote from another scientist -- Brian Greene, the physicist whose lucid writing about modern physics in his book The Fabric of the Cosmos inspired an equally brilliant NOVA series. Greene says: "Science is a way of life. Science is a perspective. Science is the process that takes us from confusion to understanding in a manner that's precise, predictive and reliable -- a transformation, for those lucky enough to experience it, that is empowering and emotional."

****************************************