Tuesday, July 8, 2025

Linguistic Calvinball

Monday, July 7, 2025

Dord, fnord, and nimrod

We were having dinner with our younger son a while back, and he asked if there was a common origin for the -naut in astronaut and the naut- in nautical.

"Yes," I said. "Latin nauta, meaning 'sailor.' Astronaut literally means 'star sailor.' Also cosmonaut, but that one came from Latin to English via Russian."

"How about juggernaut?" he asked.

"Nope," I said. "That's a false cognate. Juggernaut comes from Hindi, from the name of a god, Jagannath. Every year on the festival day for Jagannath, they'd bring out his huge stone statue on a wheeled cart, and the (probably apocryphal) story is that sometimes it would get away from them, and roll down the hill and crush people. So it became a name for a destructive force that gets out of hand."

Nathan stared at me for a moment. "How the hell do you know this stuff?" he asked.

"Two reasons. First, M.A. in historical linguistics. Second, it takes up lots of the brain space that otherwise would be used for less important stuff, like where I put my car keys and remembering to pay the utility bill."

I've been fascinated with words ever since I was little, which probably explains not only my degree but the fact that I'm a writer. And it's always been intriguing to me how words not only shift in spelling and pronunciation, but shift in meaning, and can even pop into and out of existence in strange and unpredictable ways. Take, for example, the word dord, that for eight years was in the Merriam-Webster New International Dictionary as a synonym for "density." In 1931, Austin Patterson, the chemistry editor for Merriam-Webster, sent in a handwritten editing slip for the entry for the word density, saying, "D or d, cont./density." He meant, of course, that in equations, the variable for density could either be a capital or a lower case letter d. Unfortunately, the typesetter misread it -- possibly because Patterson's writing left too little space between words -- and thought that he was proposing dord as a synonym.

Well, the chemistry editor should know, right? So into the dictionary it went.

It wasn't until 1939 that editors realized they couldn't find an etymology for dord, figured out how the mistake had come about, and the word was removed. By then, though, it had found its way into other books. It's thought that the error wasn't completely expunged until 1947 or so.

Then there's fnord, which is a word coined in 1965 by Kerry Thornley and Greg Hill as part of the sort-of-parody, sort-of-not Discordian religion's founding text Principia Discordia. It refers to a stimulus -- usually a word or a picture -- that people are trained as children not to notice consciously, but that when perceived subliminally causes feelings of unease. Government-sponsored mind-control, in other words. It really took off when it was used in the 1975 Illuminatus! Trilogy, by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, which became popular with the counterculture of the time (for obvious reasons).

Fnord isn't the only word that came into being because of a work of fiction. There's grok, meaning "to understand on a deep or visceral level," from Robert Heinlein's novel Stranger in a Strange Land. A lot of you probably know that the quark, the fundamental particle that makes up protons and neutrons, was named by physicist Murray Gell-Mann after the odd line from James Joyce's Finnegan's Wake, "Three quarks for Muster Mark." Less well known is that the familiar word robot is also a neologism from fiction, from Czech writer Karel Čapek's play R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots); robota in Czech means "hard labor, drudgery," so by extension, the word took on the meaning of the mechanical servant who performed such tasks. Our current definition -- a sophisticated mechanical device capable of highly technical work -- has come a long way from the original, which was closer to slave.

Sometimes words can, more or less accidentally, migrate even farther from their original meaning than that. Consider nimrod. It was originally a name, referenced in Genesis 10:8-9 -- "Then Cush begat Nimrod; he began to be a mighty one in the Earth. He was a mighty hunter before the Lord." Well, back in 1940, the episode of Looney Tunes called "A Wild Hare" was released, the first of many surrounding the perpetual chase between hunter Elmer Fudd and the Wascally Wabbit. In the episode, Bugs calls Elmer "a poor little Nimrod" -- poking fun at his being a hunter, and a completely inept one at that -- but the problem was that very few kids in 1940 (and probably even fewer today) understood the reference and connected it to the biblical character. Instead, they thought it was just a humorous word meaning "buffoon." The wild (and completely deserved) popularity of Bugs Bunny led to the original allusion to "a mighty hunter" being swamped; ask just about anyone today what nimrod means and they're likely to say something like "an idiot."

Saturday, July 5, 2025

Out of time

A friend of mine recently posted, "And poof! Just like that, 1975 is fifty years ago."

My response was, "Sorry. Wrong. 1975 is 25 years ago. In five years, 1975 will still be 25 years ago. That's my story, and I'm stickin' to it."

I've written here before about how plastic human memory is, but mostly I've focused on the content -- how we remember events. But equally unreliable is how we remember time. It's hard for me to fathom the fact that it's been six years since I retired from teaching. On the other hand, the last overseas trip I took -- to Iceland, in 2022 -- seems like it was a great deal longer ago than that. And 1975... well.... My own sense of temporal sequencing is, in fact, pretty faulty, and there have been times I've had to look up a time-stamped photograph, or some other certain reference point, to be sure when exactly some event had occurred.

Turns out, though, that just about all of us have inaccurate mental time-framing. And the screw-up doesn't even necessarily work the way you'd think. The assumption was -- and it makes some intuitive sense -- that memories of more recent events would be stronger than those from longer ago, and that's how your brain keeps track of when things happened. It's analogous to driving at night, and judging the distance to a car by the brightness of its headlights; dimmer lights = the oncoming car is farther away.

But just as this sense can be confounded -- a car with super-bright halogen headlights might be farther away than it seems to be -- your brain's time sequencing can be muddled by the simple expedient of repetition. Oddly, though, repetition has the unexpected effect of making an event seems like it happened further in the past than it actually did.

A new study out of Ohio State University, published this week in the journal Psychological Science, shows that when presented with the same stimulus multiple times, the estimate of when the test subject saw it for the first time became skewed by as much as twenty-five percent. It was a robust result -- holding across the majority of the hundreds of volunteers in the study -- and it came as a surprise to the researchers.

"We all know what it is like to be bombarded with the same headline day after day after day," said study co-author Sami Yousif. "We wondered whether this constant repetition of information was distorting our mental timelines... Images shown five times were remembered as having occurred even further back than those shown only two or three times. This pattern persisted across all seven sets of image conditions... We were surprised at how strong the effects were. We had a hunch that repetition might distort temporal memory, but we did not expect these distortions to be so significant."Friday, July 4, 2025

Creatures from the alongside

In C. S. Lewis's novel Perelandra, the protagonist, Elwin Ransom, goes to the planet Venus. In Lewis's fictional universe Venus isn't the scorched, acid-soaked hell we now know it to be; it's a water world, with floating islands of lush vegetation, tame animals, and a climate like something out of paradise.

In fact, to Lewis, it is paradise; a world that hasn't fallen (in the biblical sense). Ransom runs into a woman who appears to be the planet's only humanoid inhabitant, and she exhibits a combination of high intelligence and innocent naïveté that is Lewis's expression of the Edenic state. Eventually another Earth person arrives -- the scientist Weston, who is (more or less) the delegate of the Evil One, playing here the role of the Serpent. And Weston tells the woman about humanity's love for telling stories:

"That is a strange thing," she said. "To think abut what will never happen."

"Nay, in our world we do it all the time. We put words together to mean things that have never happened and places that never were: beautiful words, well put together. And then we tell them to one another. We call it stories or poetry... It is for mirth and wonder and wisdom."

"What is the wisdom in it?"

"Because the world is made up not only of what is but of what might be. Maleldil [God] knows both and wants us to know both."

"This is more than I ever thought of. The other [Ransom] has already told me things which made me feel like a tree whose branches were growing wider and wider apart. But this goes beyond all. Stepping out of what is into what might be, and talking and making things out there, alongside the world... This is a strange and great thing you are telling me."

It's more than a little ironic -- and given Lewis's impish sense of humor, I'm quite sure it was deliberate -- that a man whose fame came primarily from writing fictional stories identifies fictional stories as coming from the devil, within one of his fictional stories. Me, I'm more inclined to agree with Ralph Waldo Emerson: "Fiction reveals truth that reality obscures."

Our propensity for telling stories is curious, and it's likely that it goes a long way back. Considering the ubiquity of tales about gods and heroes, it seems certain that saying "Once upon a time..." has been going on since before we had written language. It's so familiar that we lose sight of how peculiar it is; as far as we know, we are alone amongst the nine-million-odd species in Kingdom Animalia in inventing entertaining falsehoods and sharing them with the members of our tribe.

The topic of storytelling comes up because quite by accident I stumbled on Wikipedia's page called "Lists of Legendary Creatures." It's long enough that they have individual pages for each letter of the alphabet. It launched me down a rabbit hole that I didn't emerge from for hours.

And there are some pretty fanciful denizens of the "alongside world." Here are just a few examples I thought were particularly interesting:

- The Alp-luachra of Ireland. This creature looks like a newt, and waits for someone to fall asleep by the side of the stream where it lives, then it crawls into his/her mouth and takes up residence in the stomach. There it absorbs the "quintessence" of the food, causing the person to lose weight and have no energy.

- The Popobawa of Zanzibar, a one-eyed shadowy humanoid with a sulfurous odor and wings. It visits houses at night where it looks for people (either gender) to ravish.

- The Erchitu, a were...ox. In Sardinia, people who commit crimes and don't receive the more traditional forms of justice turn on the night of the full Moon into huge oxen, which then get chased around the place being poked with skewers by demons. This is one tale I wish was true, because full Moon days in the White House and United States Congress would be really entertaining.

- The Nekomata, a cat with multiple tails that lives in the mountains regions of Japan and tricks unwary solo travelers, pretending at first to be playful and then leading them into the wilds and either losing them or else attacking them. They apparently are quite talented musicians, though.

- The Gwyllgi, one of many "big evil black dog" creatures, this one from Wales. The Gwyllgi is powerfully-built and smells bad. If you added "has no respect for personal space" and "will chase a tennis ball for hours," this would be a decent description of my dog Guinness, but Guinness comes from Pennsylvania, not Wales, so maybe that's not a match.

- The Sânziană of Romania, who is a fairy that looks like a beautiful young woman. Traditionally they dance in clearings in the forest each year on June 24, and are a danger to young men who see them -- any guy who spies the Sânziene will go mad with desire (and stay that way, apparently).

- The Ao-Ao, from the legends of the Guarani people of Paraguay. The Ao-Ao is a creature that looks kind of like a sheep, but has fangs and claws, and eats people. It is, in fact, a real baa-dass.

- The Tlahuelpuchi, of the Nahua people of central Mexico. The Tlahuelpuchi is a vampire, a human who is cursed to suck the blood of others (apparently it's very fond of babies). When it appears, it sometimes looks human but has an eerie glow; other times, it leaves its legs behind and turns into a bird. Either way, it's one seriously creepy legend.

- The Dokkaebi, a goblin-like creature from Korea. It has bulging eyes and a huge, grinning mouth filled with lots of teeth, and if it meets you it challenges you to a wrestling match. They're very powerful, but apparently they are weak on the right side, so remember that if you're ever in a wrestling match with a goblin in Korea.

So that's just the merest sampling of the creatures in the list. I encourage you to do a deeper dive. And myself, I think the whole thing is pretty cool -- a tribute to the inventiveness and creativity of the human mind. I understand why (in the context of the novel) C. S. Lewis attributed storytelling to the devil, but honestly, I can't see anything wrong with it unless you're trying to convince someone it's all true.

I mean, consider a world without stories. How impoverished would that be? So keep telling tales. It's part of what it means to be human.

Thursday, July 3, 2025

Grace under pressure

What I remember best, though, is what happened to Laëtitia Hubert. She went into the Short Program as a virtual unknown to just about everyone watching -- and skated a near-perfect program, rocketing her up to fifth place overall. From her reaction afterward it seemed like she was more shocked at her fantastic performance than anyone. It was one of those situations we've all had, where the stars align and everything goes way more brilliantly than expected -- only this was with the world watching, at one of the most publicized events of an already emotionally-fraught Winter Olympics.

This, of course, catapulted Hubert into competition with the Big Names. She went into the Long Program up against skaters of world-wide fame. And there, unlike the pure joy she showed during the Short Program, you could see the anxiety in her face even before she stated.

She completely fell apart. She had four disastrous falls, and various other stumbles and missteps. It is the one and only time I've ever seen the camera cut away from an athlete mid-performance -- as if even the media couldn't bear to watch. She dropped to, and ended at, fifteenth place overall.

It was simply awful to watch. I've always hated seeing people fail at something; witnessing embarrassing situations is almost physically painful to me. I don't really follow the Olympics (or sports in general), but over thirty years later, I still remember that night. (To be fair to Hubert -- and to end the story on a happy note -- she went on to have a successful career as a competitive skater, earning medals at several national and international events, and in fact in 1997 achieved a gold medal at the Trophée Lalique competition, bumping Olympic gold medalist Tara Lipinski into second place.)

I always think of Laëtitia Hubert whenever I think of the phenomenon of "choking under pressure." It's a response that has been studied extensively by psychologists. In fact, way back in 1908 a pair of psychologists, Robert Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson, noted the peculiar relationship between pressure and performance in what is now called the Yerkes-Dodson curve; performance improves with increasing pressure (what Yerkes and Dodson called "mental and physiological arousal"), but only up to a point. Too much pressure, and performance tanks. There have been a number of reasons suggested for this effect, one of which is that it's related to the level of a group of chemicals in the blood called glucocorticoids. The level of glucocorticoids in a person's blood has been shown to be positively correlated with long-term memory formation -- but just as with Yerkes-Dodson, only up to a point. When the levels get too high, memory formation and retention crumbles. And glucocorticoid production has been found to rise in situations that have four characteristics -- those that are novel, unpredictable, contain social or emotional risks, and/or are largely outside of our capacity to control outcomes.

Which sounds like a pretty good description of the Olympics to me.

What's still mysterious about the Yerkes-Dodson curve, and the phenomenon of choking under pressure in general, is how it evolved. How can a sudden drop in performance when the stress increases be selected for? Seems like the more stressful and risky the situation, the better you should do. You'd think the individuals who did choke when things got dangerous would be weeded out by (for example) hungry lions.

But what is curious -- and what brings the topic up today -- is that a study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed that humans aren't the only ones who choke under pressure.

So do monkeys.

In a clever set of experiments led by Adam Smoulder of Carnegie Mellon University, researchers found that giving monkeys a scaled set of rewards for completing tasks showed a positive correlation between reward level and performance, until they got to the point where success at a difficult task resulted in a huge payoff. And just like with humans, at that point, the monkeys' performance fell apart.

The authors describe the experiments as follows:

Monkeys initiated trials by placing their hand so that a cursor (red circle) fell within the start target (pale blue circle). The reach target then appeared (gray circle with orange shape) at one of two (Monkeys N and F) or eight (Monkey E) potential locations (dashed circles), where the inscribed shape’s form (Monkey N) or color (Monkeys F and E) indicated the potential reward available for a successful reach. After a short, variable delay period, the start target vanished, cueing the animal to reach the peripheral target. The animals had to quickly move the cursor into the reach target and hold for 400 ms before receiving the cued reward.And when the color (or shape) cueing the level of the reward got to the highest level -- something that only occurred in five percent of the trials, so not only was the jackpot valuable, it was rare -- the monkeys' ability to succeed dropped through the floor. What is most curious about this is that the effect didn't go away with practice; even the monkeys who had spent a lot of time mastering the skill still did poorly when the stakes were highest.

So the choking-under-pressure phenomenon isn't limited to humans, indicating it has a long evolutionary history. This also suggests that it's not due to overthinking, something that I've heard as an explanation -- that our tendency to intellectualize gets in the way. That always seemed to make some sense to me, given my experience with musical performance and stage fright. My capacity for screwing up on stage always seemed to be (1) unrelated to how much I'd practiced a piece of music once I'd passed a certain level of familiarity with it, and (2) directly connected to my own awareness of how nervous I was. I did eventually get over the worst of my stage fright, mostly from just doing it again and again without spontaneously bursting into flame. But I definitely still have moments when I think, "Oh, no, we're gonna play 'Reel St. Antoine' next and it's really hard and I'm gonna fuck it up AAAAUUUGGGH," and sure enough, that's when I would fuck it up. Those moments when I somehow prevented my brain from going into overthink-mode, and just enjoyed the music, were far more likely to go well, regardless of the difficulty of the piece.

As an aside, a suggestion by a friend -- to take a shot of scotch before performing -- did not work. Alcohol doesn't make me less nervous, it just makes me sloppier. I have heard about professional musicians taking beta blockers before performing, but that's always seemed to me to be a little dicey, given that the mechanism by which beta blockers decrease anxiety is unknown, as is their long-term effects. Also, I've heard more than one musician describe the playing of a performer on beta blockers as "soulless," as if the reduction in stress also takes away some of the intensity of emotional content we try to express in our playing.

Be that as it may, it's hard to imagine that a monkey's choking under pressure is due to the same kind of overthinking we tend to do. They're smart animals, no question about it, but I've never thought of them as having the capacity for intellectualizing a situation we have (for better or worse). So unless I'm wrong about that, and there's more self-reflection going on inside the monkey brain than I realize, there's something else going on here.

So that's our bit of curious psychological research of the day. Monkeys also choke under pressure. Now, it'd be nice to find a way to manage it that doesn't involve taking a mood-altering medication. For me, it took years of exposure therapy to manage my stage fright, and I still have bouts of it sometimes even so. It may be an evolutionarily-derived response that has a long history, and presumably some sort of beneficial function, but it certainly can be unpleasant at times.

Wednesday, July 2, 2025

Mystic mountain

The brilliant composer Alan Hovhaness's haunting second symphony is called Mysterious Mountain -- named, he said, because "mountains are symbols, like pyramids, of man's attempt to know God." Having spent a lot of time in my twenties and thirties hiking in Washington State's Olympic and Cascade Ranges, I can attest to the fact that there's something otherworldly about the high peaks. Subject to rapid and extreme weather changes, deep snowfall in the winter, and -- in some places -- having terrain so steep that no human has ever set foot there, it's no real wonder our ancestors revered mountains as the abode of the gods.

Hovhaness's symphony -- which I'm listening to as I write this -- captures that beautifully. And consider how many stories of the fantastical are set in the mountains. From Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth to Tolkien's Misty Mountains and Mines of Moria, the wild highlands (and what's beneath them) have a permanent place in our imagination.

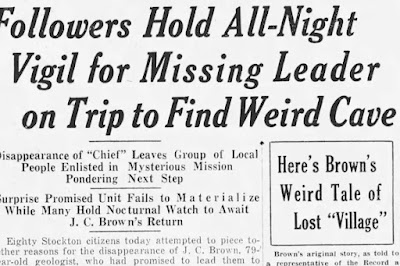

Certain mountains have accrued, usually by virtue of their size, scale, or placement, more than the usual amount of awe. Everest (of course), Denali, Mount Olympus, Vesuvius, Etna, Fujiyama, Mount Rainier, Kilimanjaro, Mount Shasta. The last-mentioned has so many legends attached to it that the subject has its own Wikipedia page. But none of the tales centering on Shasta has raised as many eyebrows amongst the modern aficionados of the paranormal as the strange story of J. C. Brown.

Brown was a British prospector, who in the early part of the twentieth century had been hired by the Lord Cowdray Mining Company of England to look for gold and other precious metals in northern California, which at the time was thousands of square miles of trackless and forested wilderness. In 1904, Brown said, he was hiking on Mount Shasta, and discovered a cave. Caves in the Cascades -- many of them lava tubes -- are not uncommon; two of my novels, Signal to Noise and Kill Switch (the latter is out of print, but hopefully will be back soon), feature unsuspecting people making discoveries in caves in the Cascades, near the Three Sisters and Mount Stuart, respectively.

Brown's cave, though, was different -- or so he said. It was eleven miles long, and led into three chambers containing a king's ransom of gold, as well as 27 skeletons that looked human but were as much as three and a half meters tall.

Brown tried to drum up some interest in his story, but most people scoffed. He apparently frequented bars in Sacramento and "told anyone who would listen." But then a different crowd got involved, and suddenly he found his tale falling on receptive ears.

Regular readers of Skeptophilia might recall a post I did last year about Lemuria, which is kind of the Indian Ocean's answer to Atlantis. Well, the occultists just loved Lemuria, especially the Skeptophilia frequent flyer Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy. So in the 1920s, there was a sudden interest in vanished continents, as well as speculation about where all the inhabitants had gone when their homes sank beneath the waves. ("They all drowned" was apparently not an acceptable answer.)

And one group said the Lemurians, who were quasi-angelic beings of huge stature and great intelligence, had vanished into underground lairs beneath the mountains.

In 1931, noted wingnut and prominent Rosicrucian -- but I repeat myself -- Harvey Spencer Lewis, using the pseudonym Wishar S[penley] Cerve (get it? It's an anagram, sneaky sneaky), published a book called Lemuria, The Lost Continent of the Pacific (yes, I know Lemuria was supposed to be in the Indian Ocean; we haven't cared about facts so far, so why start now?) in which he claimed that the main home of the displaced Lemurians was a cave complex underneath Mount Shasta. J. C. Brown read about this and said, more or less, "See? I toldja so!"Tuesday, July 1, 2025

The edges of knowledge

The brilliant British astrophysicist Becky Smethurst said, "The cutting edge of science is where all the unknowns are." And far from being a bad thing, this is exciting. When a scientist lands on something truly perplexing, that opens up fresh avenues for inquiry -- and, potentially, the discovery of something entirely new.

That's the situation we're in with our understanding of the evolution of the early universe.

You probably know that when you look out into space, you're looking back into time. Light is the fastest information carrier we know of, and it travels at... well, the speed of light, just shy of three hundred thousand kilometers per second. The farther away something is, the greater the distance the light had to cross to get to your eyes, so what you're seeing is an image of it when the light left its surface. The Sun is a little over eight light minutes away; so if the Sun were to vanish -- not a likely eventuality, fortunately -- we would have no way to know it for eight minutes. The nearest star other than the Sun, Proxima Centauri, is 4.2 light years away; the ever-intriguing star Betelgeuse, which I am so hoping goes supernova in my lifetime, is 642 light years away, so it might have blown up five hundred years ago and we'd still have another 142 years to wait for the information to get here.

This is true even of close objects, of course. You never see anything as it is; you always see it as it was. Because right now my sleeping puppy is a little closer to me than the rocking chair, I'm seeing the chair a little further in the past than I'm seeing him. But the fact remains, neither of those images are of the instantaneous present; they're ghostly traces, launched at me by light reflecting off their surfaces a minuscule fraction of a second ago.

Now that we have a new and extremely powerful tool for collecting light -- the James Webb Space Telescope -- we have a way of looking at even fainter, more distant stars and galaxies. And as Becky Smethurst put it, "In the past four years, JWST has been taking everything that we thought we knew about the early universe, and how galaxies evolve, and chucking it straight out of the window."

In a wonderful video that you all should watch, she identifies three discoveries JWST has made about the most distant reaches of the universe that still have yet to be explained: the fact that there are many more large, bright galaxies than our current model would predict are possible; that there is a much larger amount of heavy elements than expected; and the weird features called "little red dots" -- compact assemblages of cooler red stars that exhibit a strange spectrum of light and evidence of ionized hydrogen, something you generally only see in the vicinity hot, massive stars.

Well, she might have to add another one to the list. Using data from LOFAR (the Low Frequency Array), a radio telescope array in Europe, astrophysicists have found bubbles of electromagnetic radiation surrounding some of the most distant galaxies, on the order of ten billion light years away. This means we're seeing these galaxies (and their bubbles) when the universe was only one-quarter of its current age. These radio emissions seem to be coming from a halo of highly-charged particles between, and surrounding, galaxy clusters, some of the largest structures ever studied.

"It's as if we've discovered a vast cosmic ocean, where entire galaxy clusters are constantly immersed in high-energy particles," said astrophysicist Julie Hlavacek-Larrondo of the Université de Montréal, who led the study. "Galaxies appear to have been infused with these particles, and the electromagnetic radiation they emit, for billions of years longer than we realized... We are just scratching the surface of how energetic the early Universe really was. This discovery gives us a new window into how galaxy clusters grow and evolve, driven by both black holes and high-energy particle physics."

There is no learning without having to pose a question. And a question requires doubt. People search for certainty. But there is no certainty. People are terrified — how can you live and not know? It is not odd at all. You only think you know, as a matter of fact. And most of your actions are based on incomplete knowledge and you really don't know what it is all about, or what the purpose of the world is, or know a great deal of other things. It is possible to live and not know.