I keep thinking I'm not going to need to write any more about LGBTQ issues, that I've said all I need to say, and yet... here we are.

I'm going to start with a question directed at the people who are so stridently against queer rights, queer visibility, even queer existence. I doubt many people of that ilk read Skeptophilia, but you never know. So here goes:

How does guaranteeing that LGBTQ people are treated equally, fairly, and kindly, and are given the same rights as straight people, affect you at all?

It costs you absolutely nothing to say, "I'm not like you, and maybe I don't even understand this part of you, but even so, I respect your right to be who you are without shame or fear." For example, I'm not trans; I have always felt unequivocally that I am one hundred percent male. But when I had trans students in my classes, all it required was my crossing out a first name on the roster and writing in the name they'd prefer to be known by, and remembering to use the appropriate pronouns. A minuscule bit of effort on my part; hugely, and positively, significant on theirs.

What possible justification could I have for refusing?

The reason this whole topic comes up once again is a link sent to me by a loyal reader of Skeptophilia about a rugby team in Australia, the Manly Sea Eagles, which had seven of its players refuse to play in an important match because the owner wanted the team to wear jerseys with a rainbow design meant to promote inclusivity.

Retired Sea Eagles player Ian Roberts, who is the first rugby league player to come out publicly as gay, was devastated by the players' actions. "I try to see it from all perspectives, but this breaks my heart,” Roberts said. "It’s sad and uncomfortable. As an older gay man, this isn’t unfamiliar. I did wonder whether there would be any religious pushback. That’s why I think the NRL have never had a Pride round. I can promise you every young kid on the northern beaches who is dealing with their sexuality would have heard about this."

Matt Bungard, of Wide World of Sports, was blunter still. "I don’t want to hear one single thing about ‘respecting other people’s opinions’ or using religion as a crutch to hide behind while being homophobic. No issues playing at a stadium covered in alcohol and gambling sponsors, which is also a sin. What a joke."

Which I agree with completely, but it brings me back to my initial question; how did wearing the jerseys, for one night, harm those seven players? The jerseys didn't say, "Hi, I'm Gay." They were just a sign of support and inclusivity, of treating others the way you'd like to be treated.

Hmm, now where did I hear about that last bit? Seems like I remember someone famous saying that. Give me a moment, I'm sure it'll come to me.

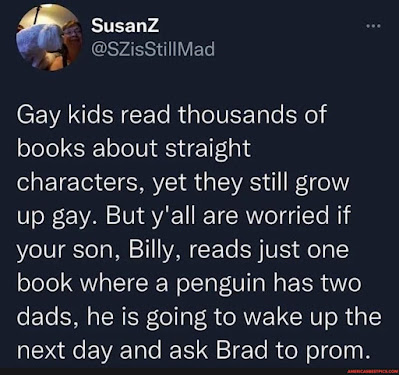

A Christian baker creating a wedding cake for a gay couple is saying, "I may not be gay, but I'm happy you've found someone you love and want to spend your life with." Straight parents who give unconditional support to their trans child are saying, "I love you no matter what, no matter who you are and what you'd like to be called." A straight teacher having books with queer representation is saying, "Even if I don't experience sexuality like you do, I want you to understand yourself and be happy and confident enough to express your own truth openly."

If you're against same-sex marriage, if you bristle at Pride events, if you refuse to use a person's chosen name and pronouns, if you think businesses should be able to deny services to queer people, I want you to stop, just for one moment, and ask yourself: how is any of this harming me? Maybe it's time to pay more attention to the "love thy neighbor" parts of the Bible than to the Book of Leviticus, of which (face it) 99% is ignored by most Christians anyway. Maybe it's time to put more emphasis on compassion, understanding, and acceptance than on condemning anyone who doesn't think, act, or believe like you do.

After all, Jesus said it himself, in the Gospel of John, chapter thirteen: "By this all people will know that you are my disciples: if you have love for one another."