Star Trek is amazing in a lot of ways, not least because of their attention to current science and an uncanny prescience about where science is heading. It turns out that we're all composite life forms. We carry around something like 39 trillion bacterial cells in and on our own bodies -- the vast majority of which are either commensals (neither helpful nor harmful) or are actually beneficial -- a number that is higher than the number of human cells we have. Each of our cells also contains mitochondria, which are the descendants of endosymbiotic bacteria that have inhabited the cells of eukaryotes for billions of years, and without which we couldn't release energy from our food molecules. Plants have not only mitochondria but chloroplasts, yet another species of bacteria that like mitochondria, have their own DNA, took up residence in their hosts billions of years ago, and have been there ever since.

But the rabbit hole goes a hell of a lot deeper than that. By some estimates, between five and eight percent of our genomes are endogenous retroviruses -- genetic fragments left behind by viruses that spliced their DNA into ours. Like our bacterial hitchhikers, a good many of these are either neutral or beneficial; for example, the production of bile, estrogen, and several proteins essential for the formation of the placenta are all directly affected by endogenous retroviral genes. A few do seem to be deleterious, and have roles in certain cancers, autoimmune diseases, and neurological disorders like ALS and schizophrenia.

What brings this topic up is an astonishing study led by Tyler Coale, of the University of California - Santa Cruz, that came out in the journal Science this week. Coale's study found there's yet another example of endosymbiosis -- this one a lot more recently evolved -- which turned a formerly free-living nitrogen-fixing bacterium into a true cellular organelle.

All these stowaways, in the cells of just about every living thing on Earth, call into question what exactly we mean not only by the word organelle but by the word organism. The high-school-biology-class definition of an organism is "an individual life form of a species." But is there any such thing? The ostensibly individual life form called Gordon who is currently writing this post is made of (at least) equal numbers of human cells and cells from different species of bacteria, without many of which I'd be sick as hell, or possibly even dead. Remove the symbiotic mitochondria from within my cells, and I'd definitely be dead -- within minutes. Deeper still, at a minimum, one in twenty of the genes in my "human DNA" comes from viruses and bacteria.

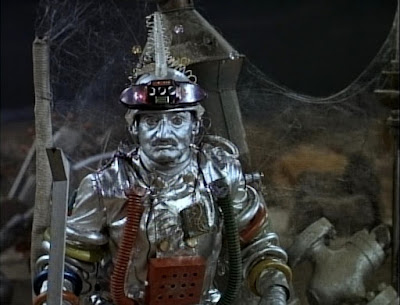

Looked at closely, I'm as put together of spare parts as the Junk Man in Lost in Space. Fortunately, I appear to run a bit more smoothly most days than he did.

In any case, calling me "a single organism" is so far from accurate it's almost laughable.

Honestly, it's kind of cool how interconnected everything is. Back in the days of the first serious taxonomist, Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus, scientists had the idea that all living things were categorizable into neat little cubbyholes. Not only is that incorrect on the species level (something I wrote about in detail a couple of years ago), it's not even true on the individual level or on the level of genomes. Life on Earth is a huge, tangled skein of threads. The whole thing puts me in mind of a quote from John Muir: "Tug at a single thing in nature, and you find that it is hitched to everything else in the universe."

****************************************

|