One of my most common reactions to woo-woos is, "What, isn't the

real world cool enough for you?"

I have a decent background (although definitely in the broad-but-shallow category) in a variety of scientific fields, and I think what impresses me about each of them is how endlessly fascinating it all is. Take your pick -- chemistry, biology, physics, astronomy, geology, climatology... you could choose any one of them, and spend the rest of your life with it, and never run out of new amazing things to discover about the field.

The downside is, it's hard work. Reality is complex. Also, virtually any scientific field will require some level of mathematical expertise; even back in the 17th century, Galileo recognized this when he said, "Mathematics is the language with which God has written the universe." And this can certainly be a stumbling block. (It was for me; my career as a physics student came to a screeching halt when I was a junior in college, largely from difficulties with the math required. Admittedly, a fondness for partying might also have had something to do with it.)

Woo-woos, on the other hand, want it easy. What "feels right?" The philosophy seems to be, "Let your heart guide you. Rationality just gets in the way." Understanding should "come naturally" -- i.e., no struggling with textbooks, no sweating over mastering abstruse equations and complicated theories. Just become One With The Universe, and you'll know all you need to know.

So let's contrast the two views of the world, shall we?

Last weekend I stumbled on the site "

Whale/Dolphin Reiki -- Celestial Pyramid Massage," which is about as good an example of the latter viewpoint as I've ever seen. This website, which is primarily an alt-med site (therapeutic massage, Reiki, chakras, flower essences, "emotion code," etc. -- they've got it all), has a page dedicated to one of the practitioners who claims that his/her skill (the author of the page isn't named, as far as I saw) from channeling "whale and dolphin spirits" who are in touch with, um, the entire galaxy. Or something.

In late 2010 I started getting information during meditations from

Whales and Usui Sensei, the Father of Reiki, that I would be a conduit

for a type of Reiki that would be coming from Whales and Dolphins from

their Source within this galaxy. The path this would take was through

Sirius. Nothing was very specific except that each session would be

tailored to the individual through a meditation before the client

arrived. I personally had issue with this as I am the type of person

that needs to know what specifically is happening and how this is to

proceed. This was a leap of faith on my part to release expectations

and the ego part of needing control and complete knowledge.

So, let me get this straight: you "need to know what specifically is happening," and so you decide you're in touch with an alien whale? The answer, apparently, is "yes:"

After more meditations I was told by Usui Sensei and the Whale Guardian

who is an Orca Whale that I needed to start giving free sessions to get

clients in and to familiarize myself with the energies coming through

and how they, the Whale and Dolphin communities, would work with me

during these sessions. Now after many clients, meditations and

communications with the Whale Guardian and others I realize that many

things seem to happen during the sessions and I have to allow the energy

to move through me at the direction of the Whale Guardian or the Whale

or Dolphin that comes in to assist the clients. At times I am

instructed as to what crystals if any to use and placement on or around

the client.

Okay. The "Whale Guardian" told you to use crystals, for what, exactly?

Issues that seem to be concentrated on the most are grounding and

balancing of the physical body with the earth mostly with the

crystalline core of the earth. I have also been told that neuro

pathways within the brain are made that opens communications within the

multi-dimensional layers of the body. In some instances more work seems

to concentrate on the pineal and pituitary glands clearing and cleaning

debris that has built up around these glands by food additives and

pollution. These changes increase the client’s vibration and frequency

which allows acceptance physically as the earth increases in vibration

and frequency.

*faceplant*

So, there you have it, then. A whale that's in contact with the galaxy told these people to use Reiki to clean up the schmutz on your pituitary gland left there by consuming food additives.

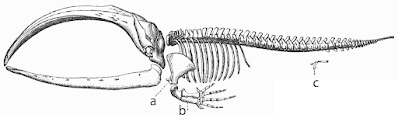

Now, let's contrast this to some actual scientific research -- a project in

Orca communication done by the Marine Mammal Research Consortium:

Killer whales extensively

rely on sound for orientation, prey detection, and communication.

Different types of sounds fulfill different functions for killer whales.

Echolocation clicks, for example, are used for orientation and prey

detection. Whistles are high-frequency sounds typically used by killer

whales in social contexts, and pulsed calls are communicative sounds

thought to play a role in the coordination of behaviours and maintenance

of group cohesion.

Isn't that nice? No vague, hand-waving "energies" and "vibrations;" just some real information about what whales are really doing:

Pulsed calls can be categorized into

highly stereotyped call types. Different social groups within the

same population have group-specific repertoires of different call

types. As a result, resident killer whales in British Columbia and

Alaska exhibit an intricate system of vocal dialects. The structure

of these call types evolves slowly over time and is thought to be

learned.

And, most importantly, it's all backed up by data -- sonograms, recordings, and behavioral observations collected over years of research. I encourage you to peruse the site, and then come back and try to tell me that's not more interesting than the Alien Whale Crystal Massage thing.

It's not that I don't understand the temptation of easy answers. I've found myself frustrated with how hard science can be. I've struggled with comprehension, misunderstood things, gotten things wrong, had to go back and revise my mental model of how the world works. More importantly, I've had to get used to admitting, "I don't know the answer to this."

Tolerating uncertainty, however, is uncomfortable for a lot of people. For some, it's a happier solution just to embrace what "feels nice," to go along with the pleasant fiction of whale spirits communicating with aliens from Sirius, or whatever weird mythological view of the universe suits their fancy. But I can't escape the conclusion that by doing so, they've cheated themselves of the joy that comes from catching a glimpse of the actual grandeur of what is around us -- that ecstatic moment when you say, "Yes, I understand!"

And there is no amount of comforting fiction that is worth taking in trade for that.