For a long time, one of the biggest evolutionary mysteries was the evolution of whales and dolphins.

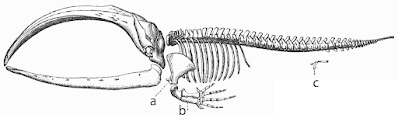

Even for someone steeped in the evolutionary model, it was hard to imagine how these aquatic creatures descended from terrestrial mammals. That they did was undeniable; not only do some species have vestigial hip and hind leg bones, inside their flippers they have exactly the same number and arrangement of arm bones as you have -- one humerus, radius, and ulna; seven carpals; five metacarpals; and fourteen phalanges. If whales were a "special creation," it's hard to imagine why a Creator would have given them 29 articulated arm bones and then completely encased them in a flat, muscular flipper.

So their relationship to terrestrial mammals was obvious, but what wasn't obvious is how they got to where they are today.

Then in 1981 a fossil bed was uncovered in the Kuldana Formation of Pakistan, a sedimentary deposit from what was a shallow marine estuary back in the early Eocene Epoch (on the order of fifty million years ago), that contained a treasure trove of fossilized cetaceans. This allowed researchers to piece together the evolution of whales and dolphins, placing them in Order Artiodactyla (their closest terrestrial relatives appear to be hippos).

Back in the Eocene, some of these proto-cetaceans were some badass apex predators. Take Basilosaurus -- the name is Greek for "king lizard," a misnomer, at least the "lizard" part -- which lived in the Tethys Ocean, a body of water that has since been largely erased by plate tectonics. (The Mediterranean, Black, and Caspian Seas are about all that's left of it.) Basilosaurus could get to twenty meters in length, and probably ate large fish like sharks and tuna. It's Basilosaurus that got me to thinking about this topic in the first place; a couple of loyal readers of Skeptophilia sent me a link to an article about a new fossil discovery in Peru. It's hard to imagine it, but the now bone-dry Ocucaje Desert of southern Peru was once the floor of a shallow sea, an embayment of the (at that point) rapidly shrinking Tethys. It's provided huge numbers of Eocene fossils, but the one they just found is pretty spectacular; a complete, well-preserved skull of a Basilosaurus that when it was alive was on the order of seventeen meters from tip to tail.

"This is an extraordinary find because of its great state of preservation," said Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi, part of the team that found the fossil. "This animal was one of the largest predators of its time. At that time the Peruvian sea was warm. Thanks to this type of fossil, we can reconstruct the history of the Peruvian sea."**************************************

No comments:

Post a Comment