One of the features of linguistics I find the most interesting is regional accents.

Americans are usually aware of this phenomenon apropos of English in the United States; it doesn't take any great skill to detect a difference between speech amongst natives of Maine, Mississippi, and Minnesota. It's a phenomenon that is hardly limited to the US, however. I heard loud and clear the differences between English spoken in Cornwall, Suffolk, Yorkshire, and Durham when I was in England. And I still recall when I was in a band that played French music, and we had a gig at Cornell University. Afterward, a very nice couple with a distinctly French-from-France accent came up afterward.

"We loved your singing," they said to me, "and your French is excellent. But where are you from? You don't sound Parisian or any of the accents from southern France, and you're definitely not Québecois."

I said, "My family is from Louisiana."

The light bulb went on. "Ah!" the man said, smiling. "Of course!"

I guess the Cajun still comes through, even though I haven't lived in my home state in forty years.

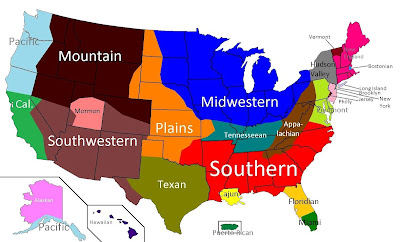

What I find even more interesting is how resistant my English-speaking accent has been to change, despite living in YankeeLand for decades. I took the New York Times Accent Quiz, and even though I feel like my mode of speech has been pretty well homogenized from ten years in Seattle and thirty in upstate New York, the three cities that I scored the highest matches with were Shreveport, Louisiana, Biloxi, Mississippi, and Houston, Texas.

Connect those three into a triangle, and where I grew up is pretty much right in the middle.

The test relies not only on differences in pronunciation (e.g., of the words "merry," "Mary," and "marry," which ones, if any, are said the same way?) but in identifiable regional words. For example:

- What do you call the children's playground equipment that's a long board that pivots in the middle, so two kids on opposite ends can take turns going up and down?

- What do you call the strip of ground running along the side of a road?

- What do you call fizzy sweetened drinks?

- What do you call a machine affixed to a wall that provides cold water to drink?

- What do you call a residential road with a green space running down the middle?

(My answers, if you're curious: teeter-totter, verge, soda, water fountain, boulevard.)

Of course, there are a few dead giveaways. My use of the word "y'all" as a second-person plural pronoun pinpoints me in the southeast of the country right from the outset. And there are a few bizarre regionalisms -- the most striking one, that none of my friends who took the test had even heard of, is the strange expression "the devil is beating his wife" for the phenomenon of rain falling while the sun is shining. (No, I have no idea where it comes from, but I can remember my dad saying that when I was little. Apparently it is of uniquely southern-Louisiana provenance.)

What brings this up is a study from the University of Pennsylvania that appeared in the journal Language last week, looking not only at regional accents but in an odd phenomenon called linguistic convergence -- that people tend to imitate the accents they hear, often unconsciously, resulting in phonetic conventions not native to the person's own region or ethnic background showing up in their speech.

The specific one they looked at was the so-called "long i" sound, more technically the diphthong /ai/, as found in the English words "ride" and "dine." In a lot of parts of the American southeast, that diphthong gets flattened out to /æ/, the vowel sound in the standard English pronunciation of "cat."

What they found was that if a (non-southeastern US) English-speaking test subject was exposed to someone who did have a southeastern accent -- but who had been instructed beforehand not to use any words that had the /ai/ -> /æ/ diphthong shift -- and then instructed to read a list of words, the test subject was more likely to say something closer to /ræd/ and /dæn/ than the standard pronunciations of /raid/ and /dain/.

Evidently hearing southeastern accents makes you likely to adopt southeastern-sounding phonetics, even if you haven't heard the particular phonetic shift in question.

What's interesting about this is that it's not only unconscious, it's temporary -- when time has elapsed and speech is heard using the test subject's native regional accent, the effect goes away. But we apparently have a mental representation of what "talking southern" sounds like, and that finds its way into our speech when we hear it.

My wife, I've noticed, has a tendency to do this -- she picks up accents, and has to work actively to halt it (she's very conscious of not wanting people to think she's mimicking or mocking them). I'm not sure if I do it -- I'll have to ask her to pay attention next time we're in a place where the accent is different from mine.

My question, of course, is why? Humans learn a lot when we're little through mirroring both what we hear and what we see. Is this a holdover from the way we learn language when we're children? Or is it some kind of unconscious attempt to fit in with the people we're talking to, to seem less "other" than we would have? The underlying cause was beyond the scope of the current research, but it's an interesting question about something that seems to be a universal tendency.

So next time you're around someone who speaks with a different accent than yours, keep your ears perked. I wonder if the fact that you're now aware of this will make it less likely to happen? Maybe your accent will bleed over into the person you're talking to. Let me know what happens to y'all, y'hear?

**************************************