Back when I was teaching, I ran into students with a lot of fringe-y beliefs, or at least unscientific ones. But if you had to pick which one students were the most reluctant to abandon, I bet you'd never guess.

Dowsing.

Dowsing, also called water-witching, is the belief that you can use a forked stick (more modern dowsers use a pair of metal rods on a swivel) to locate stuff. It started out being used to find underground water for a well (thus the appellation "water-witching"), but has since progressed (or regressed? Guess it depends upon your viewpoint) to being used to find all sorts of things, including -- I kid you not -- marijuana in kids' lockers in a high school.

"But it works!" students said, when I told them there was no scientific basis for it whatsoever. "My dad hired a guy to come tell us where to dig our well, and we hit water at only thirty feet down!"

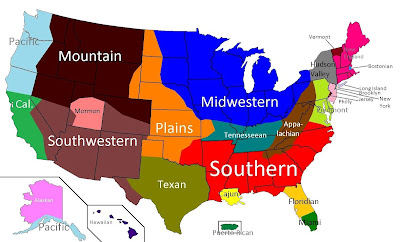

Yeah, okay. But this is upstate New York, one of the cloudiest, rainiest climates in the United States. Unless you're standing on an outcropping of bedrock, there's gonna be groundwater underneath you. In fact, only about twenty miles from here, there's a hillside with a natural artesian spring -- someone put a pipe into it, and people stop and fill up water bottles from the clear water gushing out. So it's entirely unsurprising that you hit water where the dowsing guy indicated. You'll hit water pretty much anywhere around here if you dig down a ways.

What's funniest are the quasi-scientific explanations the dowsers give as to why it (allegedly) works. An example is that you should always make your dowsing rod from a willow branch, because willows grow near water, so the wood remains attracted to it. Even though I'm yet to see how a dead branch could respond that way. Or any way, honestly.

Given that it's dead.

Every scientifically-valid study of dowsing has resulted in zero evidence that it works. This doesn't mean the dowsers are deliberately cheating; they may honestly think the stick is moving on its own. This is called the ideomotor effect, where small movements made unconsciously by the practitioner convince him/her (and the audience) that something real, and supernatural, is going on. (The same phenomenon almost certainly accounts for spiritualist claims like Ouija board divination and table-turning.)

But despite these sorts of arguments, I fear that I convinced few students to change their beliefs. "I saw it happen!" is a remarkably powerful mindset, even once you accept that we're all prone to biases, and that we're all easily fooled when it comes to something we want to believe.

So this is why I was unsurprised but disheartened to read an article from Mother Jones sent to me by a long-time loyal reader of Skeptophilia. In it, we read about one Arpad Vass, a guy who believes that you can use dowsing rods...

... to find dead bodies.

This would just be another goofy belief, and heaven knows those are a dime a dozen, but he has somehow convinced the people who run the National Forensic Academy in Oak Ridge, Tennessee that his technique is scientifically sound. He has some kind of cockeyed explanation of how it works -- that the effect is due to piezoelectricity, a phenomenon where certain crystalline substances develop a charge when they're subjected to mechanical stress. Piezoelectricity is real enough; it's the basis of quartz watches, inkjet printing, and electric guitar pickups. But even if decomposing bone can generate some net static charge, it would leak away into the soil it's buried in -- there's no mechanism by which it could exert a pull on some bent wires several meters away. (Actually, Vass claims he's successfully found corpses this way from a hundred meters away. If the static charge is that high, you shouldn't need a dowsing rod to detect it -- a plain old boring volt meter would work. Funny how that never happens.)

And, of course, there's the problem that it doesn't work for everyone. Vass has an answer for that, too. "If people don’t have the right voltage, it’s not going to work," he says. "Everything in the universe vibrates at a very specific frequency. Gold has a gold frequency, silver has a silver frequency, and your DNA has your frequency."

I guess bullshit has a specific frequency, too.

The problem is that Vass isn't just playing around, or doing something that isn't a huge deal if it doesn't work (like finding a well drilling site). This is injecting pseudoscience into police investigation. And recently, he's gone one step further; he has invented, he said, a "quantum oscillator" that supposedly picks up a person's "frequency" from something like a hair sample or fingernail clippings, and then beams that frequency out, and it will somehow interact with the person (or his/her corpse), and send back a signal to the device...

... from up to 120 kilometers away.

I was encouraged by the fact that the Mother Jones article came down fairly solidly on the side of the scientists, stating unequivocally that there is no evidence that any form of dowsing works. They also highlighted the human side of this; Randy Shrewsberry, founder of the nonprofit Criminal Justice Training Reform Institute, was quoted as saying "Law enforcement regularly accepts the flaws of these practices despite the life-altering impacts that can occur when they’re wrong." In one Virginia case, a man was convicted of murder even though no body of the victim was found -- in part, because of testimony from Vass that his device had found the victim's "frequency" in eight locations, indicating that her body had been dismembered.

Eric Bartelink, professor of anthropology at the University of California - Chico and former president of the American Board of Forensic Anthropology, was unequivocal. "Vass is operating these services that are not scientifically valid. It’s very misleading to families and law enforcement."

So at least some prominent voices in the field are speaking up to support the findings of every scientific study ever done on the practice of dowsing. I'm still appalled that a forensic training academy has somehow been convinced to take Vass and his nonsense seriously; I guess being highly educated isn't necessarily an immunization against confirmation bias. As for me, I'm calling bullshit on the whole practice.

Beam that into your "quantum oscillator," buddy.

**************************************