Today's topic comes to us not because it's some earthshattering discovery that overturns what we've understood, but solely because it's really cool.

You probably know the general rule that isolated ecosystems -- islands, especially -- tend to evolve in their own direction, resulting in a flora and fauna that is completely unique. Two of the most common places cited as illustrations of this general rule are Australia and Madagascar, home to two of the oddest collections of species on Earth. Australia's species are so different from the (relatively) nearby biomes in southeast Asia that it was noticed over 150 years ago by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, and the boundary was named "Wallace's Line" in his honor. It's an amazingly sharp edge. Wallace's Line runs between Borneo (to the west) and Sulawesi (to the east), and between Bali (to the west) and Lombok (to the east); the distance between Bali and Lombok is only 35 kilometers, but their flora and fauna are so different it was apparent to Wallace immediately. North and west of Wallace's Line, the animals and plants are the typical assemblage you see in all of southeast Asia. South and east of it, you get the families you find in Australia.

Another case of this was the linkup of North and South America, forming the Isthmus of Panama three million years ago. Prior to this, South America had been isolated for 150 million years, resulting in the evolution of a completely unique group of living things, including the giant ground sloth (Megatherium) and the armored-tank glyptodons. When the connection formed, this allowed the North American carnivores (especially dogs, cats, and weasels) to migrate south. Humans eventually followed. The result -- extinction of most of the South American megafauna. (One of the only species to make the return trip successfully is the armadillo.)

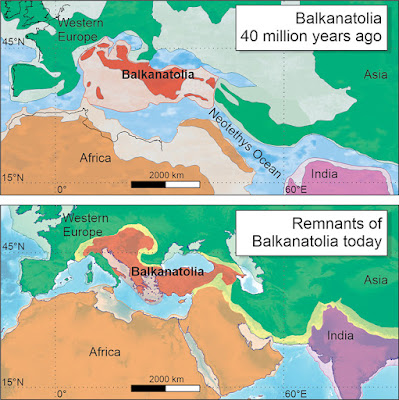

The research that brings this topic up is a study showing that this kind of thing has been going on throughout the Earth's history. In this case, a team of paleontologists and geologists has shown that a similar scenario unfolded forty million years ago, during the Eocene Epoch, when three land masses collided -- what are now Europe and western Asia, and a low-lying island in between that has been named Balkanatolia (because what's left of it now forms the Balkans and Anatolia). Here is the layout prior to the collision, and where those land masses are today:

Sometimes, who wins and who loses is due as much to luck as it is to fitness. The species that became extinct in these continental fusion events were doing just fine before the land masses linked together; had North and South America not joined, we might well have giant ground sloths and glyptodons today. (Of course, those kinds of counterfactual speculation are probably pointless. Any number of things besides predation by North American mammals could have led to the extinctions. After all, there have been a lot of changes, climatic and otherwise, since then, and megafauna always seem to get hit hardest by rapidly-shifting conditions.)

But it's cool to find another example of this effect. And it also gives us a hint of what's to come. The Australian Plate is moving generally northward at about seven centimeters per year, and will inevitably collide with Asia in a hundred million years or so. This fusion will erase Wallace's Line and allow for mixing of the two faunal and floral assemblages.

Who will win? No way to tell, but considering how badass some of the Australian animals are (saltwater crocodiles, cassowaries, brown snakes and taipans, and funnel-web spiders, to name just a few), I'm putting my money on the Land Down Under.

**************************************