|

Tuesday, September 17, 2024

A circle of light

Thursday, February 24, 2022

Continental mashup

Today's topic comes to us not because it's some earthshattering discovery that overturns what we've understood, but solely because it's really cool.

You probably know the general rule that isolated ecosystems -- islands, especially -- tend to evolve in their own direction, resulting in a flora and fauna that is completely unique. Two of the most common places cited as illustrations of this general rule are Australia and Madagascar, home to two of the oddest collections of species on Earth. Australia's species are so different from the (relatively) nearby biomes in southeast Asia that it was noticed over 150 years ago by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, and the boundary was named "Wallace's Line" in his honor. It's an amazingly sharp edge. Wallace's Line runs between Borneo (to the west) and Sulawesi (to the east), and between Bali (to the west) and Lombok (to the east); the distance between Bali and Lombok is only 35 kilometers, but their flora and fauna are so different it was apparent to Wallace immediately. North and west of Wallace's Line, the animals and plants are the typical assemblage you see in all of southeast Asia. South and east of it, you get the families you find in Australia.

Another case of this was the linkup of North and South America, forming the Isthmus of Panama three million years ago. Prior to this, South America had been isolated for 150 million years, resulting in the evolution of a completely unique group of living things, including the giant ground sloth (Megatherium) and the armored-tank glyptodons. When the connection formed, this allowed the North American carnivores (especially dogs, cats, and weasels) to migrate south. Humans eventually followed. The result -- extinction of most of the South American megafauna. (One of the only species to make the return trip successfully is the armadillo.)

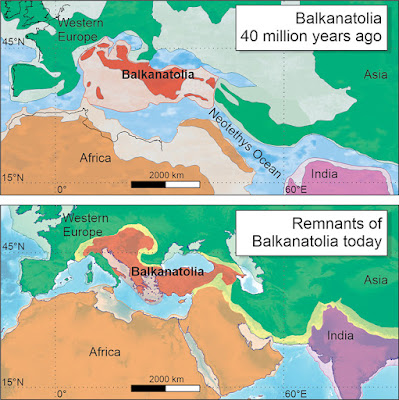

The research that brings this topic up is a study showing that this kind of thing has been going on throughout the Earth's history. In this case, a team of paleontologists and geologists has shown that a similar scenario unfolded forty million years ago, during the Eocene Epoch, when three land masses collided -- what are now Europe and western Asia, and a low-lying island in between that has been named Balkanatolia (because what's left of it now forms the Balkans and Anatolia). Here is the layout prior to the collision, and where those land masses are today:

Sometimes, who wins and who loses is due as much to luck as it is to fitness. The species that became extinct in these continental fusion events were doing just fine before the land masses linked together; had North and South America not joined, we might well have giant ground sloths and glyptodons today. (Of course, those kinds of counterfactual speculation are probably pointless. Any number of things besides predation by North American mammals could have led to the extinctions. After all, there have been a lot of changes, climatic and otherwise, since then, and megafauna always seem to get hit hardest by rapidly-shifting conditions.)

But it's cool to find another example of this effect. And it also gives us a hint of what's to come. The Australian Plate is moving generally northward at about seven centimeters per year, and will inevitably collide with Asia in a hundred million years or so. This fusion will erase Wallace's Line and allow for mixing of the two faunal and floral assemblages.

Who will win? No way to tell, but considering how badass some of the Australian animals are (saltwater crocodiles, cassowaries, brown snakes and taipans, and funnel-web spiders, to name just a few), I'm putting my money on the Land Down Under.

**************************************

Saturday, August 1, 2020

Death in the seas

- The Ordovician-Silurian Extinction (440 million years ago)

- The Devonian Extinction (365 million years ago)

- The Permian-Triassic Extinction (250 million years ago)

- The Triassic-Jurassic Extinction (210 million years ago)

- The Cretaceous-Tertiary Extinction (66 million years ago)

The end of the Pliocene marked the beginning of a period of great climatic variability and sea-level oscillations. Here, based on a new analysis of the fossil record, we identify a previously unrecognized extinction event among marine megafauna (mammals, seabirds, turtles and sharks) during this time, with extinction rates three times higher than in the rest of the Cenozoic, and with 36% of Pliocene genera failing to survive into the Pleistocene. To gauge the potential consequences of this event for ecosystem functioning, we evaluate its impacts on functional diversity, focusing on the 86% of the megafauna genera that are associated with coastal habitats. Seven (14%) coastal functional entities (unique trait combinations) disappeared, along with 17% of functional richness (volume of the functional space).A loss of 36% of the marine genera is huge. Especially when you consider that some of the vanished species weren't exactly tiny obscure sea bugs. One of the victims was Carcharodon megalodon, the largest shark species known, which reached a length of fifteen meters from tip to tail and weighed upward of fifty metric tons. What seems to have hidden this event from view is that it mainly impacted marine organisms, whose remains may well have been fossilized, but most of which are still underwater (there hasn't been that much large-scale geological shift in two million years, so most Pliocene-age rocks are pretty much still sitting where they formed).

The surmise by the scientists is that the Pliocene-Pleistocene Extinction was caused by large-scale sea level fluctuations altering oceanic current patterns and eradicating coastal habitat. Climate change today seems to be aiming toward a similar target. "This study shows that marine megafauna were far more vulnerable to global environmental changes in the recent geological past than had previously been assumed," said study lead author Catalina Pimiento. "This also points to a present-day parallel: Nowadays, large marine species such as whales or seals are also highly vulnerable to human influences."

So here we have another cautionary tale, if we needed one. Once again, marine mammals are at risk, but this time it's human activity that's driving the change. Polar bears -- sometimes referred to as the "poster child for climate change" -- are likely to be extinct by 2100 if we stay on the trajectory we're on.

You have to wonder what future paleontologists will make of our age. Will the sedimentary rocks forming today tell the story of a sudden, drastic decrease in biodiversity? Will there be any way to tell what caused it? Who will be the winners -- and who the losers?

And most frightening of all, will we still be around to consider the question?

*****************************

Being in the middle of a pandemic, we're constantly being urged to wash our hands and/or use hand sanitizer. It's not a bad idea, of course; multiple studies have shown that communicable diseases spread far less readily if people take the simple precaution of a thirty-second hand-washing with soap.

But as a culture, we're pretty obsessed with cleanliness. Consider how many commercial products -- soaps, shampoos, body washes, and so on -- are dedicated solely to cleaning our skin. Then there are all the products intended to return back to our skin and hair what the first set of products removed; the whole range of conditioners, softeners, lotions, and oils.

How much of this is necessary, or even beneficial? That's the topic of the new book Clean: The New Science of Skin by doctor and journalist James Hamblin, who considers all of this and more -- the role of hyper-cleanliness in allergies, asthma, and eczema, and fascinating and recently-discovered information about our skin microbiome, the bacteria that colonize our skin and which are actually beneficial to our overall health. Along the way, he questions things a lot of us take for granted... such as whether we should be showering daily.

It's a fascinating read, and looks at the question from a data-based, scientific standpoint. Hamblin has put together the most recent evidence on how we should treat the surfaces of our own bodies -- and asks questions that are sure to generate a wealth of discussion.

[Note: if you purchase this book using the image/link below, part of the proceeds goes to support Skeptophilia!]

Thursday, April 16, 2020

Five-part wake-up call

"Thanks to this model, we can confidently say a long and profound global anoxic event is linked to the second pulse of mass extinction in the Late Ordovician," said study co-author Erik Sperling of Stanford University. "For most ocean life, the Hirnantian-Rhuddanian boundary [between the end of the Ordovician and the beginning of the Silurian] was indeed a really bad time to be alive."

Beyond deepening understandings of ancient mass extinction events, the findings have relevance for today: Global climate change is contributing to declining oxygen levels in the open ocean and coastal waters, a process that likely spells doom for a variety of species.Then there's the press release from McGill University about another extinction event, the one that happened at the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic Periods, 201 million years ago. This one was also a bit of a mystery, but now the researchers have a smoking gun. Guess what it is?

Changes in the atmosphere.

Here, massive volcanic eruptions (okay, "massive" isn't sufficient; "fucking huge" comes close) occurred as the Central Atlantic Rift Zone opened up, which was eventually to push apart Europe and Africa from North and South America, creating the Atlantic Ocean. But this research indicates that the initial eruption happened over only five hundred years, and spewed out 100,000 cubic kilometers of lava.

That's a cubical block, one kilometer on each edge, but 100,000 of them.

Like I said. Fucking huge.

What the problem was, other than for anything in the way of the lava flows, was the carbon emissions. Not only does lava itself usually contain dissolved carbon dioxide that is released upon eruption, there's all the carbon generated by the lava burning up plants and other organic material. The amount of carbon pumped into the atmosphere by this event was said by the press release to "be equivalent to the [predicted] total produced by all human activity during the 21st century."

When I got to this sentence, I said, and I quote, "What?" The amount of carbon released by human activity in the 21st century is predicted to be equal to the amount generated by a 100,000 cubic kilometer lava flow, only five times faster?

At this point, I said some other stuff, which I won't include because I've already said "fucking" twice in this post.

Now, on to the ones that apply directly to our situation here and now.

First, a study out of the University of Sydney of estuaries, the points where freshwater rivers run into oceans. These are biologically productive areas, homes to not only abundant sea life but fisheries industries that support coastal economies. What this study found is that the water in estuaries is warming at twice the rate of the rest of the world's oceans -- which could be catastrophic. In the words of the press release:

The researchers say that changes in estuarine temperature, acidity and salinity are likely to reduce the global profitability of aquaculture and wild fisheries. Global aquaculture is worth $US243.5 billion a year and wild fisheries, much of which occurs in estuaries, is worth $US152 billion. More than 55 million people globally rely on these industries for income.Be aware, too, that this temperature increase is not a prediction. It's already happened. "This is evidence that climate change has arrived in Australia; it is not a projection based on modelling, but empirical data from more than a decade of investigation," said Elliot Scanes, who co-authored the paper, which appeared this week in Nature Communications. "This increase in temperature is an order of magnitude faster than predicted by global ocean and atmospheric models."

Last, there are two studies, both in the journal Nature. One focused on projections of biodiversity loss in Africa and predicted that the crash was set to happen a lot sooner in the tropics than initially thought, and that the losses would be significantly impacting economies in the 2030s. Like, ten years from now. And it's not as if we here in the Frozen North will be spared; the same models predicted this devastation to spread to temperate ecosystems by 2050. The final study modeled the economic impact of the current target of keeping the global average temperature increase between 1.5 and 2 C over the next eighty years. I'd like to quote directly from this one, because paraphrasing just wouldn't have the same impact:

Results show that following the current emissions reduction efforts, the whole world would experience a washout of benefit, amounting to almost 126.68–616.12 trillion dollars until 2100 compared to 1.5 °C or well below 2 °C commensurate action. If countries are even unable to implement their current NDCs, the whole world would lose more benefit, almost 149.78–791.98 trillion dollars until 2100.The authors of this study call keeping the warming threshold below 1.5 C "a matter of simple self-preservation."

Five studies, all basically with the same message: when this happened in the past, the consequences were horrifying; it's happening now; and we damn well better get up off our asses and do something about it. Not that this is likely with Emperor Donald the Demented in charge, not to mention his corporate-boot-licking yes-men and women in Congress.

The most frustrating thing for me about all of this is that we've known about all this for ages. Thirty years ago, Irish science historian James Burke released his amazing two-part documentary After the Warming, which was prescient in so many ways that it beggars belief. But these lines always have stood out to me: "Where they [are getting] it really wrong is the argument over whether the greenhouse effect is happening [now]... which is irrelevant. The question is what to do about the fact that scientific opinion thought that it would strike sooner or later. Still, for some people, that wasn't good enough reason to spend money preparing for the eventuality, even though they paid to insure their lives, their homes, and their national defense against much less likely events."

So it's an open question if we'll do anything now, given our abysmal track record of taking the information we already have and acting on it. I'm hoping that the information campaigns to bring this to the attention of the public, both by humble bloggers like myself and the scientific experts who know the most, are waking people up, even if only a few at a time.

My only fear is that a few at a time won't be enough to stave off catastrophe.

********************************

This week's Skeptophilia book recommendation of the week is brand new -- only published three weeks ago. Neil Shubin, who became famous for his wonderful book on human evolution Your Inner Fish, has a fantastic new book out -- Some Assembly Required: Decoding Four Billion Years of Life, from Ancient Fossils to DNA.

Shubin's lucid prose makes for fascinating reading, as he takes you down the four-billion-year path from the first simple cells to the biodiversity of the modern Earth, wrapping in not only what we've discovered from the fossil record but the most recent innovations in DNA analysis that demonstrate our common ancestry with every other life form on the planet. It's a wonderful survey of our current state of knowledge of evolutionary science, and will engage both scientist and layperson alike. Get Shubin's latest -- and fasten your seatbelts for a wild ride through time.