Friday, September 23, 2022

The orphan

Thursday, September 22, 2022

Look me in the eye

Wednesday, September 21, 2022

Memory offload

"What have you learned by doing that?" I recall asking him, trying to keep the frustration out of my voice.

"I got the right answer," he said.

"But the answer isn't the point!" Okay, at that point my frustration was pretty clear.

I think the issue I had with this student comes from two sources. One is the education system's unfortunate emphasis on Getting The Right Answer -- that if you have The Right Answer on your paper, it doesn't matter how you got it, or whether you really understand how to get there. But the other is our increasing reliance on what amounts to external memory. When we don't know something, the ease and accessibility of answers online makes us default to that, rather than taking the time to search our own memories for the answer.

The loss of our own facility for recall because of the external storage of information was the subject of a study in the journal Memory. Called "Cognitive Offloading: How the Internet is Increasingly Taking Over Human Memory," the study, by cognitive psychologists Benjamin Storm, Sean Stone, and Aaron Benjamin, looked at how people approach the recall of information, and found that once someone has started relying on the internet, it becomes the go-to source, superseding one's own memory:

The results revealed that participants who previously used the Internet to gain information were significantly more likely to revert to Google for subsequent questions than those who relied on memory. Participants also spent less time consulting their own memory before reaching for the Internet; they were not only more likely to do it again, they were likely to do it much more quickly. Remarkably, 30% of participants who previously consulted the Internet failed to even attempt to answer a single simple question from memory.

"Memory is changing," lead author Storm said. "Our research shows that as we use the Internet to support and extend our memory we become more reliant on it. Whereas before we might have tried to recall something on our own, now we don't bother. As more information becomes available via smartphones and other devices, we become progressively more reliant on it in our daily lives."

What concerns me is something that the researchers say was outside the scope of their research; what effect this might have on our own cognitive processes. It's one thing if the internet becomes our default, but that our memories are still there, unaltered, should the Almighty Google not be available. It's entirely another if our continual reliance on external "offloaded" memory ultimately weakens our own ability to process, store, and recall. It's not as far-fetched as it sounds; there have been studies that suggest that mental activity can stave off or slow down dementia, so the "if you don't use it, you lose it" aphorism may work just as much for our brains as it does for our muscles.

In any case, maybe it'd be a good idea for all of us to put away the electronics. No one questions the benefits of weightlifting if you're trying to gain strength; maybe we should push ourselves into the mental weightlifting of processing and recalling without leaning on the crutch of the internet. And as Kallian discovers in The Scattering Winds, the bounty of information that comes from the external storage of information -- be it online or in print -- comes at a significant cost to our own reverence for knowledge and depth of understanding.

Tuesday, September 20, 2022

Fish tales

Undoubtedly you are aware of the outrage from people on the anti-woke end of the spectrum about Disney's choice of Black actress Halle Bailey to play Ariel in their upcoming live-action remake of The Little Mermaid.

This is just the latest in a very long line of people getting their panties in a twist over what fictional characters "really" are, all of which conveniently ignores the meaning of the words "fictional" and "really." Authors, screenwriters, and casters are free to reimagine a fictional character any way they want to -- take, for example, the revision of The Wizard of Oz's Wicked Witch of the West into the tortured heroine in Gregory Maguire's novel (and later Broadway hit) Wicked. This one didn't cause much of a stir amongst the I Hate Diversity crowd, though, undoubtedly because the character of the Witch stayed green the whole time.

But that's the exception. In the past, we've had:

- A French professor claiming the Smurfs are communists

- An Islamic cleric issuing a fatwa against Mickey Mouse

- Right-wing media calling Dora the Explorer an illegal immigrant

- The Vatican declaring that the Simpsons are Roman Catholic

The current uproar, of course, is worse; not only is it blatantly racist, it's aimed at a real person, the actress who will play Ariel. But these lunatics show every day that they care more about fictional characters than they do about actual people; note that the same folks screeching about Black mermaids seem to have zero problem with using public funds to transport actual living, breathing human beings to another state, where they were dropped on a street corner like so much refuse, in order to own the libs.

Oh, but you can't mess about with the skin color of mermaids. In fact, the outrage over this was so intense that it has triggered some of them to invoke something they never otherwise give a second thought to:

Science.

Yes, if you thought this story couldn't get any more idiotic, think again. Now we have members of the Mermaid Racial Purity Squad claiming that mermaids can't be Black, because they live underwater, and if you're underwater you can't produce melanin.

I wish I was making this up. Here's a direct quote:

Mermaids live in ocean. Underwater = limited sunlight. Limited sunlight = less melanin. Less melanin = lighter skin color. Because they live underwater, which has no access to light beyond a certain depth, Ariel and every other mermaid in existence would be albino.

And another:

Correct me if I'm wrong. But isn't it physically impossible for Ariel to be black? She lives underwater, how would the sun get to her for her to produce melanin?! Nobody thought this through..?

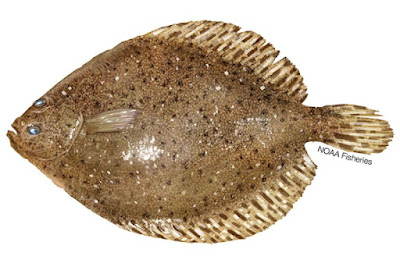

Okay, well, correct me if I'm wrong, but applying science to a movie in which there's a singing, dancing crab, a sea witch with octopus legs, and a character named Flounder who clearly isn't a flounder is kind of a losing proposition from the get-go.

Plus, there are plenty of underwater animals that aren't white, which you'd think would occur to these people when they recall the last science book they read, which was One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish by Dr. Seuss.

Oh, and another thing. It's an ironic fact that the squawking knuckle-draggers who complain about "wokeness" every time some fictional character they like isn't played by a White American and are the same ones who pitch a fit at any kind of representation of diversity, be it in books, movies, music, or whatever, conveniently overlook the fact that (1) Hans Christian Andersen, who wrote The Little Mermaid, was bisexual, and (2) there's a credible argument that the original story itself was inspired by his grief at having his romantic advances rejected by his friend Edvard Collin. (In fact, in the original story, the mermaid doesn't marry the prince -- he goes off and marries a human girl, just as Collin himself did, and the mermaid weeps herself to death. Not a fan of happy endings, Andersen.)

Anyhow, anti-woke people, do go on and tell me more about "reality" and "what science says." Hell, have at it, apply science anywhere you want. Start with climate change and environmental policy if you like. Or... does it only matter to you when the subject is people who aren't the right color, gender, ethnic origin, nationality, or sexual orientation?

Monday, September 19, 2022

Long live the king

Those of you who are interested in the affairs of the royal family of Great Britain will no doubt want to know that the psychics have weighed in on the future of newly-crowned King Charles III.

According to an article Thursday in the Hull Daily Mail, the loyal subjects of His Majesty are in for a bit of a rollercoaster. One Mario Reading, author and expert in interpreting the writings of Nostradamus, predicts that Charles III isn't going to be king for long. He's going to abdicate, Reading says. "Prince Charles will be 74 years old in 2022, when he takes over the throne. But the resentments held against him by a certain proportion of the British population, following his divorce from Diana, Princess of Wales, still persist."

After that, things get even weirder. Citing Nostradamus's line "A man will replace him who never expected to be king," Reading says that after Charles's abdication, the next king will not be his elder son William. It could be that his younger son, Prince Harry, will reign as King Henry IX... or possibly someone even wilder. An Australian guy named Simon Dorante-Day, who claims he is the secret son of King Charles and the Queen Consort Camilla, might be ready to take the crown once Charles steps aside.

"It’s certainly food for thought, because the prediction makes it clear that someone out of left field would replace Charles as king," Dorante-Day said. "I can see why some people would think I fit the bill. I believe I am the son of Charles and Camilla and I’m looking forward to my day in court to prove this. Maybe Nostradamus has the same understanding that I do, that all this will come out one day."

Saturday, September 17, 2022

The will to fight

If you're fortunate enough not to suffer from crippling depression and anxiety, let me give you a picture of what it's like.

Last week I started an online class focused on how to use TikTok as a way for authors to promote their books. So I got the app and created an account -- it's not a social media platform I'd used before -- and made my first short intro video. I was actually kind of excited, because it seemed like it could be fun, and heaven knows I need some help in the self-promotion department. (As an aside, if you're on TikTok and would like to follow me, here's the link to my page.)

Unfortunately, it seemed like as soon as I signed up, I started having technical problems. I couldn't do the very first assignment because my account was apparently disabled, and that (very simple) function was unavailable. Day two, I couldn't do the assignment because I lacked a piece of equipment I needed. (That one was my fault; I thought it was on the "optional accessories" list, but I was remembering wrong.) Day three's assignment -- same as day one; another function was blocked for my account. By now, I was getting ridiculously frustrated, watching all my classmates post their successful assignments while I was completely stalled, and told my wife I was ready to give up. I was getting ugly flashbacks of being in college physics and math classes, where everyone else seemed to be getting it with ease, and I was totally at sea. When the same damn thing happened on day four, my wife (who is very much a "we can fix this" type and also a techno-whiz), said, "Let me take a look." After a couple of hours of jiggering around with the settings, she seemed to have fixed the problem, and all the functions I'd been lacking were restored.

The next morning, when I got up and got my cup of coffee and thought, "Okay, let me see if I can get started catching up," I opened the app and it immediately crashed.

Tried it again. Crash. Uninstalled and reinstalled the app. Crash.

I think anyone would be frustrated at this point, but my internal voices were screaming, "GIVE UP. YOU SHOULD NEVER HAVE SIGNED UP FOR THIS. YOU CAN'T DO IT. IT FIGURES. LOSER." And over and over, like a litany, "Why bother. Why bother with anything." Instead of the frustration spurring me to look for a solution, it triggered my brain to go into overdrive demanding that I give up and never try again.

When I heard my wife's alarm go off an hour later, I went and told her what had happened, trying not to frame it the way I wanted to, which was "... so fuck everything." She sleepily said, "Have you tried turning your phone completely off, then turning it back on?" Ah, yes, the classic go-to for computer problems, and it hadn't occurred to me. So I did...

... and the app sprang back to life.

But now I was on day five of a ten-day course, and already four assignments behind. That's when the paralyzing anxiety kicked in. I had told the instructors of the course a little about my tech woes, and I already felt like I had been an unmitigated pest, so the natural course of action -- thinking, "you paid for this course, tell the instructors and see if they can help you catch up" -- filled me with dread. I hate being The Guy Who Needs Special Help. I just want to do my assignments, keep my head down, fly under the radar, be the reliable work-horse who gets stuff done. And here I was -- seemingly the only one in the class who was being thwarted by mysterious forces at every turn.

So I never asked. The more help I needed, the more invisible I became. It's now day seven, and I'm maybe halfway caught up, and I still can't bring myself to tell them the full story of what was going on.

Adversity > freak out and give up. Then blame yourself and decide you should never try anything new ever again. That's depression and anxiety.

I've had this reaction pretty much all my life, and it's absolutely miserable. It most definitely isn't what I was accused of over and over as a child -- that I was choosing to be this way to "get attention" or to "make people feel sorry for me." Why the fuck would anyone choose to live like this? All I wanted as a kid -- all I still want, honestly -- is to be normal, not to have my damn brain sabotage me any time the slightest thing goes wrong. As I told my wife -- who, as you might imagine, has the patience of a saint -- "some days I would give every cent I have to get a brain transplant."

So re: TikTok, if Carol hadn't been there, I'd have deleted my account and forfeited the tuition for the class. But I'm happy to report that I haven't given up, and I've posted a few hopefully mildly entertaining videos, which I encourage you to peruse.

The reason all this comes up, though, isn't just because of my social media woes. I decided to write about this because of some research published this week in the journal Translational Psychiatry which found that a single gene -- called Tob -- seems to mediate resilience to emotional stress in mice, and without it, produces exactly the "freak out and give up" response people have when they suffer from depression and anxiety.

Tob was already the subject of intense research because it apparently plays a role in the regulation of the cell cycle, cancer suppression, and the immune system. It's known that in high-stress situations, Tob rapidly switches on, so it is involved somehow in the flight-fight-freeze response. And a team led by Tadashi Yamamoto of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology found that "Tob-knockout mice" -- mice that have been genetically engineered to lack the Tob gene -- simply gave up when they were in stressful situations requiring resilience and sustained effort. Put another way, without Tob, they completely lost the will to fight.

When I read this article -- which I came across while I was in the midst of my struggle with technology -- I immediately thought, "Good heavens, that's me." Could my tendency to become frustrated and overwhelmed easily, and then give up in despair, be due to the underactivity of a gene? I know that depression and anxiety run in my family; my mother and maternal grandmother definitely struggled with them, as does my elder son. Of course, it's hard to tease apart the nature/nurture effects in this kind of situation. It's a reasonable surmise that being raised around anxious, stressed people would make a kid anxious and stressed.

But it also makes a great deal of sense that these familial patterns of mental illness could be because there's a faulty gene involved.

Research like Yamamoto et al. is actually encouraging; identifying a genetic underpinning to mental illnesses like the one I have suffered from my entire life opens up a possible target for treatment. Because believe me, I wouldn't wish this on anyone. While fighting with a silly social media platform might seem to someone who isn't mentally ill like a shrug-inducing, "it's no big deal, why are you getting so upset?" situation, for people like me, everything is a big deal. I've always envied people who seem to be able to let things roll off them; whatever the reason, if it came from the environment I grew up in or because I have a defective Tob gene, I've never been able to do that. Fortunately, my family and friends are loving and supportive and understand what I go through sometimes, and are there to help.

But wouldn't it be wonderful if this kind of thing could be fixed permanently?

Friday, September 16, 2022

Rebuilding the web

One of the (many) ways people can be shortsighted is in their seeming determination to view non-human species as inconsequential except insofar as they have a direct benefit to humans.

The truth, of course, is a great deal more nuanced than that. One well-studied example is the reintroduction of gray wolves to Yellowstone National Park, something that was opposed by ranchers who owned land adjacent to the park, hunters who were concerned that wolves would reduce numbers of deer, elk, and moose for hunting, and people worried that wolves might attack humans visiting the park or the area surrounding it. The latter, especially, is ridiculous; between 2002 and 2020 there were 489 verified wolf/human attacks worldwide, of which a little over three-quarters occurred because the animal was rabid. Only eight were fatal. The study, carried out by scientists at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, stated outright that the risks associated with a wolf attacking a human were "non-zero, but far too low to calculate."

Fortunately, wiser heads prevailed, and the wolf reintroduction went forward as scheduled, starting in 1996. The results were nothing short of spectacular. Elk populations had skyrocketed following the destruction of the pre-existing wolf population in the early twentieth century, resulting in such high overgrazing that willows and aspens were virtually eradicated from the park. This caused the beaver population to plummet, as well as several species of songbirds that depend on the insects hosted by those trees. The drop in the number of beaver colonies meant less damming of streams, resulting in small creeks drying up completely in summer and a resultant crash of fish populations.

In the years since wolves were reintroduced, all of that has reversed. Elk populations have returned to stable numbers (and far fewer die of starvation in the winter). Aspen and willow groves have come back, along with the beavers and songbirds that depend on them. The ponds and wetlands are rebuilding, and the fish that declined so precipitously have begun to rebound.

All of which illustrates the truth of the famous quote by naturalist John Muir: "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe."

The reason this all comes up is a recent story in Science News about a project that should give you hope; the restoration of mangrove forests in Kenya. You probably know that mangroves are a group of trees that form impenetrable thickets along coastlines. They've been eradicated in a lot of places -- particularly stretches of coast with sandy shores potentially attractive to tourists -- resulting in increased erosion and drastically increased damage potential from hurricanes. A 2020 study found that having an intact mangrove buffer zone along a coast decreased the damage to human settlements and agricultural land from a direct hurricane strike by an average of 24%.

The Kenyan project, however, was driven by two other benefits of mangrove preservation and reintroduction -- carbon sequestration and increased fish yields. Mangrove swamps have been shown to be four times better at carbon capture and storage as inland forests, and their tangled submerged root systems are havens for hatchling fish and the plankton they eat. The restoration has been successful enough that similar projects have been launched in Mozambique and Madagascar. A UN-funded project called Mikoko Pamoja allows communities that are involved in mangrove restoration to receive money for "carbon credits" that then can be reinvested into the community infrastructure -- with the result that the towns of Gazi and Makongeni, nearest to the mangrove swamps and responsible for their protection, have become economically self-sufficient.

I have the feeling that small, locally-run projects like Mikoko Pamoja will be how we'll save our global ecosystem -- and, most importantly, realizing that species having no immediately obvious direct benefit to humans (like wolves and mangroves) are nevertheless critical for maintaining the health of the complex, interlocked web of life we all depend on. It means taking our blinders off, and understanding that our everyday actions do have an impact. I'll end with a quote from one of my heroes, the late Kenyan activist Wangari Maathai: "In order to accomplish anything," she said, "we must keep our feelings of empowerment ahead of our feelings of despair. We cannot do everything, but still there are many things we can do."

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)